South America grasslands

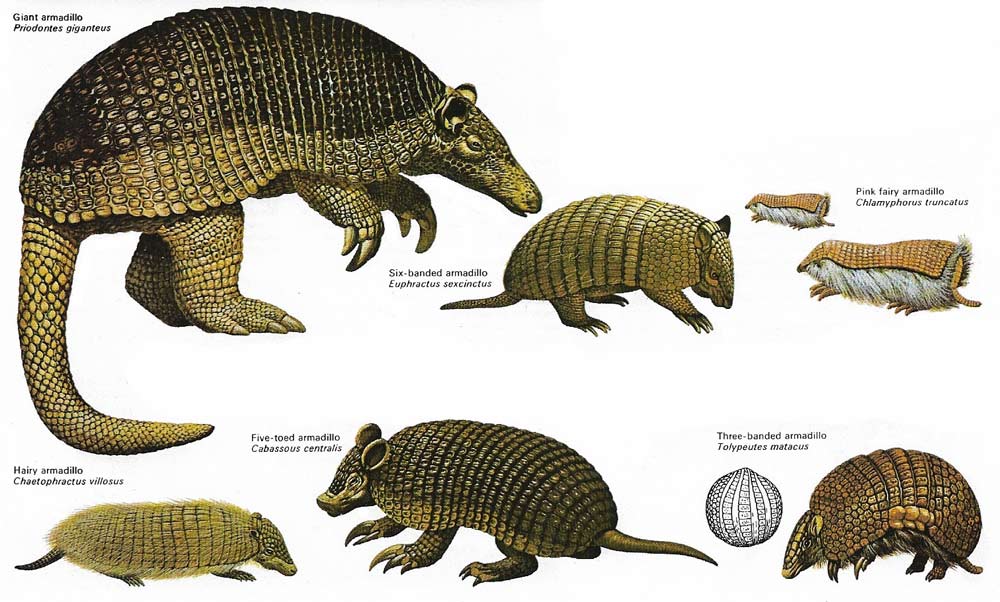

The 21 species of armadillo are among the most abundant and widespread of South American mammals. Uniquely protected by plates of bone joined with skin, a few of the, such as the three-banded armadillo, can roll themselves into defensive balls when threatened. But most escape predators by rapid burrowing. Armadillos vary in size from the giant armadillo, 1.5 meters (5 feet) in length and weighing up to 50 kilograms (110 pounds), to the fairy armadillos are regarded as pests in some areas but they do help man by ridding his crops of harmful insects and other small animals.

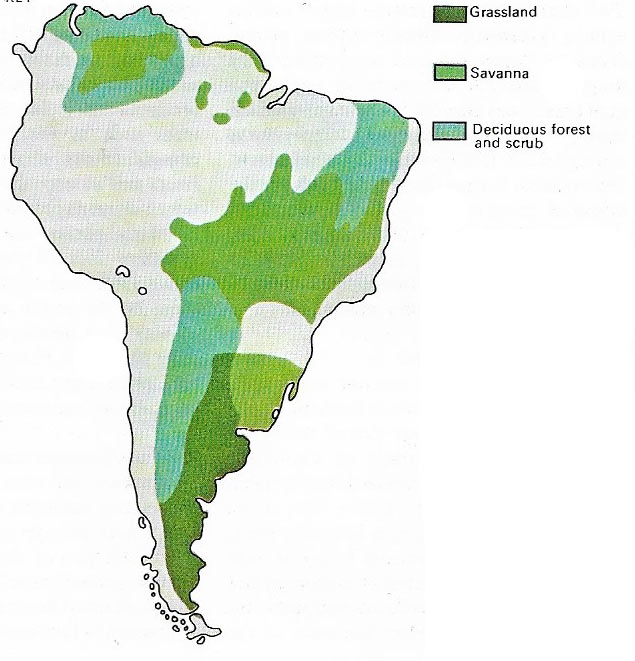

Figure 1. The grasslands of South America cover much of the continent east of the Andes. The vast, treeless Argentine pampas merges into forest in the wetter northeast and into scrub and desert to the west and south. In the north it is bounded by the Chaco – an area of deciduous woodland and scrub. The Venezuelan llanos and Brazilian campos are areas of tall-grassed savanna interspersed with forest.

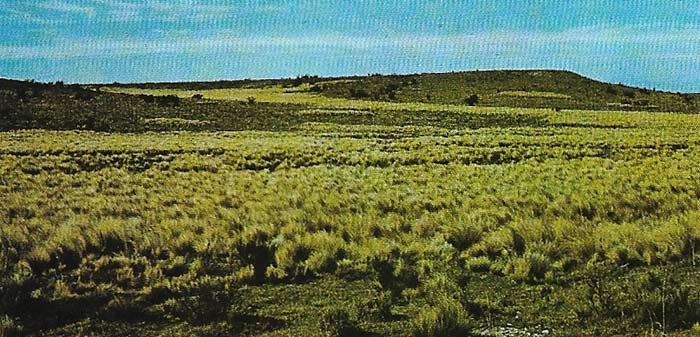

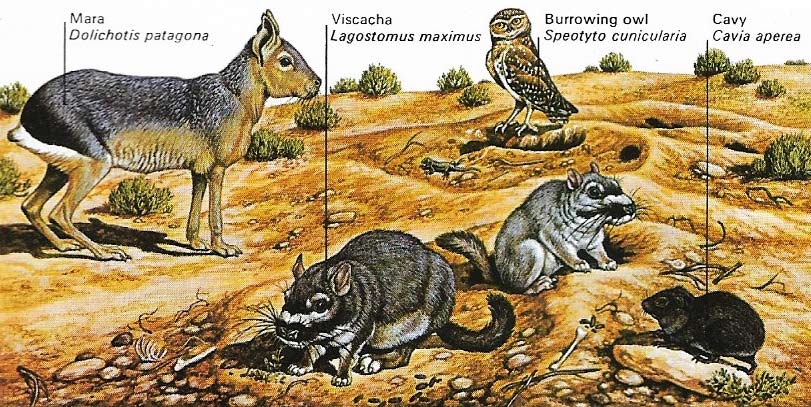

Figure 2. The first Argentine pampas covers more than 500,000 square kilometers (350,000 square miles). In the east moist Atlantic winds promote the growth of rich, tall grass; but near the Andes a hot, dry climate produces an arid steppe land with bare soil patches between tufts of prairie grass and drought-resistant bushes. Many pampas animals in these harsh regions live underground for at least part of their lives.

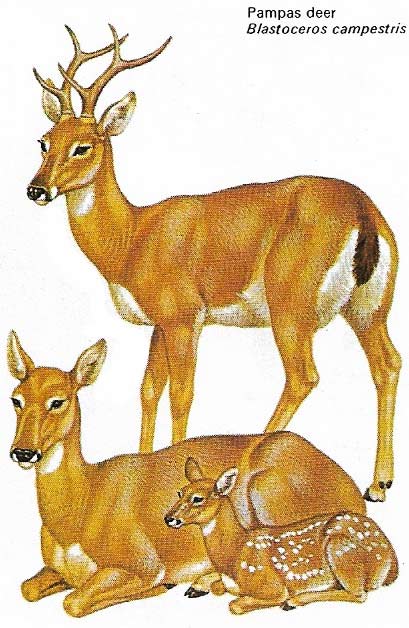

Figure 3. The pampas deer is one of the few herbivorous mammals of any size to be found on the South American grasslands. Its numbers have now been seriously reduced as a result of over-hunting and the destruction of its habitat by ranching and cultivation.

Figure 4. The viscacha digs a system of tunnels it shares with the burrowing owl and the Mara or Patagonian hare. By stripping the surrounding area of vegetation the viscacha can detect approaching predators. The pampas cavy nests at the base of grass tufts.

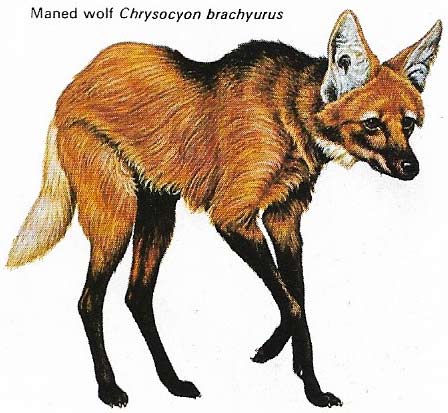

Figure 5. The shy, nocturnal maned wolf, like other plains predators, will eat almost anything from small animals to fruit.

Figure 6. The giant anteater rips open termite mounds and scoops the termites with its long, sticky tongue. Its shaggy coat protects it from bites.

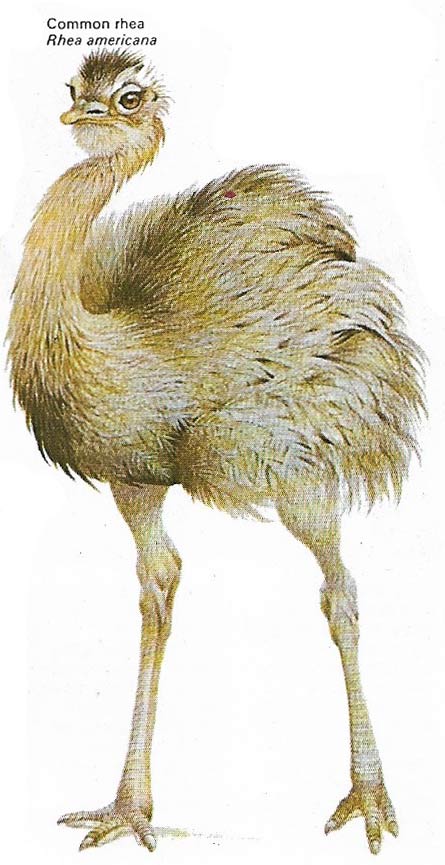

Figure 7. The flightless rhea or South American ostrich, a bird that lives in open country, roams the pampas in flocks of up to 30, feeding on vegetation and insects. It stands up to 1.5 meters (4.6 feet) tall and can detect approaching danger even in high grass. When threatened it can run faster than a horse.

From the Brazilian highlands and dense forests of Amazonia southwards to the barren lands of Patagonia, and from the eastern slopes of the Andes to the Atlantic Ocean, stretches a vast ocean of grassland. This is a region where droughts are frequent and where torrential downpours penetrate only the top layers of soil. As a result, trees are unable to compete with shallow-rooted grass plants which take the available water.

Grasslands and climate

The type of grassland, and therefore the kind of animals it supports, depends largely on rainfall and temperature. Hot, dusty summers, cold, windy winters, and alternate periods of drought and heavy rainfall have produced the huge expanse of temperate grassland called the Argentine pampas (Figure 2). On this plain, formed by layers of soil weathered from the Andes and carried eastward by rivers toward the sea, the controlling influence of soil moisture on vegetation is apparent. On the wetter, eastern side the grass grows in tall, course tufts and eventually merges into forest. The fertility of this part of the pampas has been made use of by man for widescale ranching and agriculture and, as a result, the landscape has been considerably modified. On the drier western and southern margins bare soil patches are found between clumps of prairie grass, and drought-resistant bushes and small scrub trees replace the grassland. Farther to the east the scrub gradually gives way to desert.

Animals large and small

Most of the large animals that inhabited these grasslands when South America was an isolated continent disappeared about a million years ago when the isthmus of Panama was formed and carnivores travelled southward from North America. The carnivores were unable to cope with the conditions successfully, could not colonize, and eventually died out. As a result the only animals in the South American grasslands today are those that have managed to adapt to the climate and food supplies of the area. The only mammal of any size on the pampas is the pampas deer (Blastoceros campestris) (Figure 3) and the largest animal inhabitant is a bird, the rhea (Rhea americana) (Figure 7). This flightless bird, the South American counterpart of the ostrich, is well suited to an open habitat. Its long legs give it an elevated view of its surroundings and enable it to run at more than 50 kilometers per hour (30 mph). In spite of the absence of large mammals at ground level the grasslands teem with life. There may be as many as 1,000 surface insects per square meter (11 square feet), particularly grasshoppers and butterflies. They and the numerous lizards, snakes, and spiders provide food for the predatory birds and mammals.

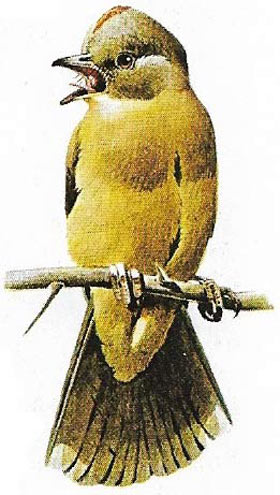

It is the small mammals, however, that have made best use of the ground cover and are most characteristic of the grasslands. Many of them solve the problems of climatic extremes and a lack of suitable hiding places by living underground for at least part of their lives, and, as a result, burrowing rodents such as the viscacha (Lagostomus maximus) (Fig 4) and the noisy tucu-tucu (Ctenomys talarum) are among the most successful grassland inhabitants. For much of the day they remain hidden in their underground tunnels, coming out to feed only in the safety of darkness. The wild guinea pig (Cavia aperea) (Figure 4), which lives above ground, seeks protection by forming large colonies of up to several hundred and only emerges from tufts of grass to feed at dawn and dusk. Rodents form a large part of the diet of grassland predators such as the pampas fox (Dusicyon gymnocercus) and the Azara's opossum (Didelphis azarae). But extremes of climate and erratic rainfall make food supplies unreliable, so many predators are omnivorous and will eat almost anything they can find. Numerous other predators, such as armadillos (top illustration), skunks, and anteaters, forage in the grass for abundant insect life. Birds such as the smooth-billed anis (Grotophaga ani) and the aptly-named cattle tyrant (Machetornis rixosus) find their food by following grazing animals. They then catch the thousands of insects disturbed from the ground vegetation.

|

| The cattle tyrant is a flycatcher that perches on the backs of hoofed mammals waiting for insects disturbed by the grazing animals. It has an erectile crest of feathers. |

|

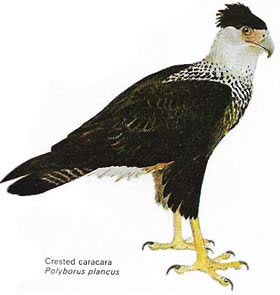

| The crested cara-cara, a ground dwelling falcon that is both hunter and scavenger, searches the grassy plains for food both living and dead with a characteristic head-bobbing walk. |  |

| The southern screamer haunts marshy areas of the pampas with harsh cries. Its slightly webbed feet enable it to walk on floating vegetation. |

Many of the avian inhabitants of the pampas are migrant visitors. In autumn the golden plover (Pluvialis dominica) leaves the harsh conditions in the tundra and flies nearly 16,000 kilometers (7,500 miles) to winter in the grasslands before returning to its nesting grounds in spring. Many northern shore birds, such as the redshanks and sandpipers, also migrate there in winter to feed on the fish and insects in marshy areas of the pampas.

The Chaco and its wildlife

Large expanses of water are also typical of an area to the north of the pampas called the Chaco – a transitional zone between the grassland and the tropical forests of the Amazon that lacks a specialized fauna but attracts animals from neighboring zones. Sluggish rivers spread out over a large plain to form swamps. These become shallow lakes during the heavy summer rains and form a paradise for water-birds such as limpkins, ducks, and noisy screamers. The swamps, often inhabited by the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) (Figure 6), are interspersed with patches of grassland and deciduous forest. The forest is the home of the giant armadillo (Priodontes giganteus) (top illustration) and the elusive maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) (Figure 5) which, although well adapted to plains life, seeks shelter of trees.