sea urchin

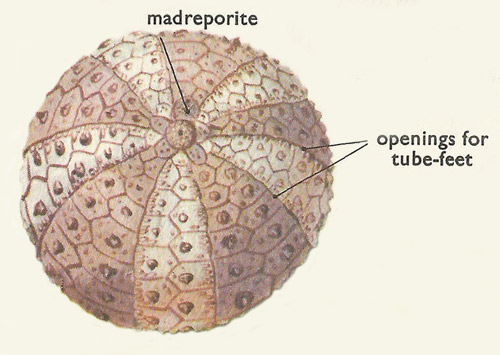

Figure 1. Shell of a sea urchin.

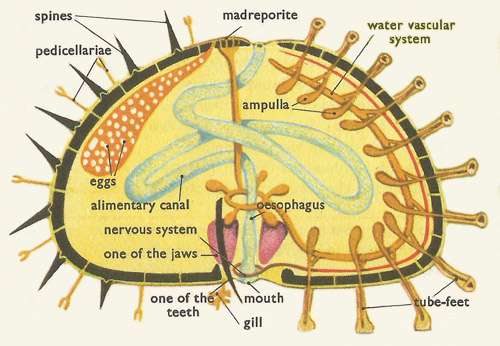

Figure 2. Diagrammatic section of a sea urchin.

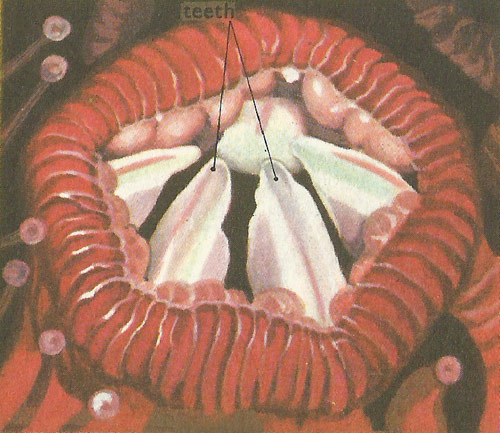

Figure 3. Mouth of a sea urchin.

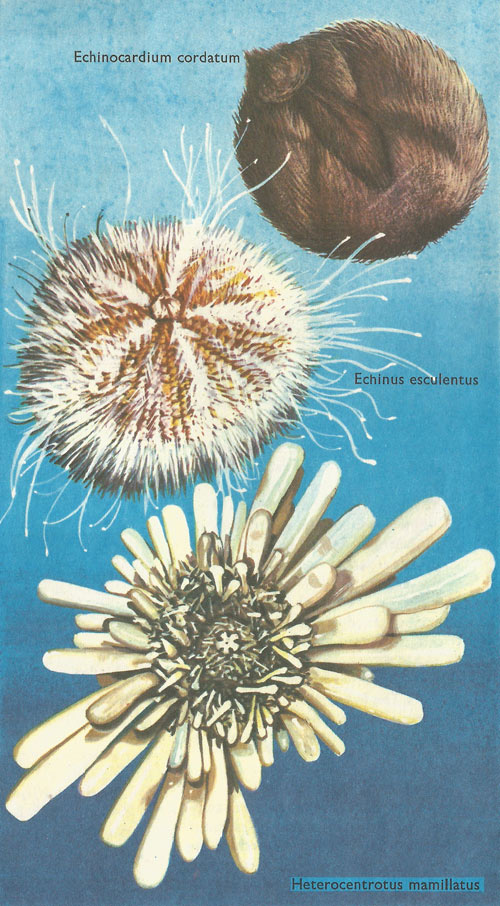

Figure 4. Echinocardium cordatum. A bilaterally symmetrical species, sometimes called the heart-urchin on account of its shape. It has fine spines like bristles, and is common on sandy shores, where it burrows to a depth of about 3 in. Empty shells are often washed up; they are white and have usually lost their spines. Echinus esculentus, common sea urchin. This species is common on British shores; in the Mediterranean countries it is collected and used for food. Heterocentrotus mamillatus, slate-pencil urchin. A species with very thick spines the lives in the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

A sea urchin is a globular echinoderm (class Echinoidea), the body of which is formed by fused skeletal plates bearing moveable spines. The plates forming the shell are in ten double bands or columns, five of which have openings for tube feet (Fig 1). The anus is usually on the upper surface and the mouth on the lower surface. Sea urchins have a complex jaw apparatus called Aristotle's lantern. They feed by scavenging, grazing, or ingesting sediment. Approximately 5,000 fossil species and 950 living species are known, including sand dollars and heart urchins.

|

| The tube-feet of a sea urchin are seen, in close-up, to be capped by suction pads. When the feet contact a solid surface, the center of the sucker is withdrawn, producing a vacuum and adhesion. Contraction of muscles and removal of water from the feet lifts them from the surface once more. In this way the sea urchin can move rapidly over rocks and even climb vertical surfaces.

|

Radial symmetry

Most animals, including ourselves, are made on a plan of bilateral symmetry – they can be divided into two more or less identical halves, a right and a left. The echinoderms are usually radially symmetrical – their parts are arranged around a central axis like the spokes of a wheel or the petals of many flowers. The normal number of radii or 'spokes' is five. Some of the 'cake-urchins' are bilaterally symmetrical, though the five rays can still be seen. This five-symmetry is shared by no other animals.

Mouth

The mouth of a sea urchin is on its lower surface; inside it there is a peculiar structure, rather fancifully called 'Aristotle's lantern'. It consists of five complicated 'jaws', all joined together to form a cone-shaped structure; each jaw has a sharp tooth at lower end, and the tips of the teeth can be seen through the mouth (Figure 3).

Pedicellariae

|

All sea urchins and many starfish also have numerous little two- or three-fingered pincers on their bodies, called pedicellariae. A three-fingered one is shown in the diagram above. They are used for removing mud or sand from their bodies, capturing prey, and for self-defence. The pedicellariae of some tropical sea urchins have poison glands and are formidable weapons.

Spines

In warm seas, where there are rocks or coral, sea urchins with long, black spines are abundant. These spines are sharp, and easily pierce your skin if your brush against them; they nearly always break off, leaving the tips in your flesh. As they are barbed, they are difficult to pull out. Some species have thick, blunt spines; of these are broken, the fracture has the form of flat planes, showing that each spine is a complete crystal of calcite, or calcium carbonate.