spider

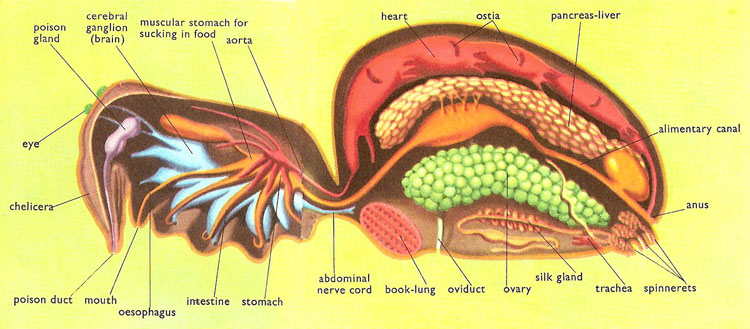

Figure 1. Internal anatomy of a spider.

Figure 2. A Black and Yellow Argiope in its web. Credit: National Park Service.

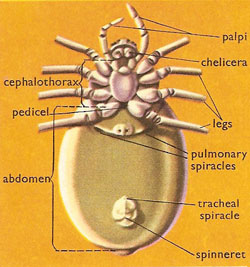

Figure 3. A spider seen from underneath.

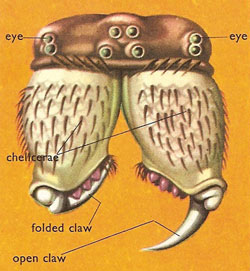

Figure 4. Face of a garden spider.

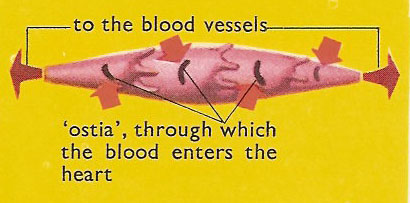

Figure 5. The spider's heart takes the form of a simple tube, open at each end, having apertures called 'ostia' at the sides.

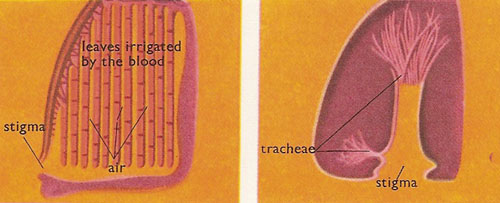

Figure 6. (Left) Book-lungs of a spider. (Right) Branching of the trachea.

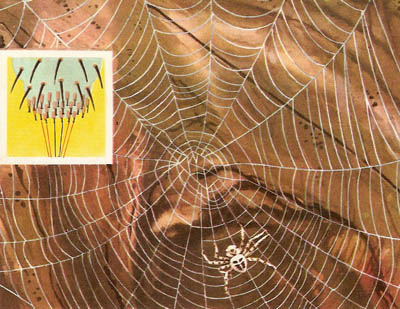

Figure 7. A garden spider at work on her web. Above left: a spinneret greatly enlarged.

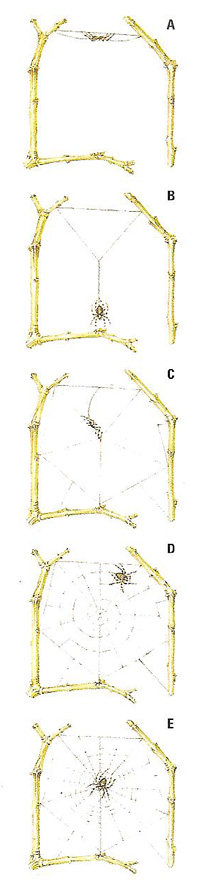

Figure 8. When spinning its web for catching prey, the spider first casts out a thread of silk to form a horizontal strut (A). A second, drooping thread is trailed across below the bridge-line. Halfway along the second thread, the spider drops down on a vertical thread until it reaches a fixed object (B). It pulls the silk taut and anchors it, forming a "Y" shape, the center of which forms the hub of the web. The spider then spins the framework threads and the radials, which are linked together at the hub (C). After spinning the remainder of the radials, a wide, temporary spiral of dry silk is laid down, working from the inside of the web outwards (D). This holds the web together while the spider lays down the sticky spiral. This is laid down starting from the outside, and is attached successively to each radial thread (E). The spider eats the remains of the dry spiral as it proceeds. The central dry spirals are left as a platform for the spider, which will often lie in wait there during the night. In the daytime the spider retreats to a nearby silk shelter.

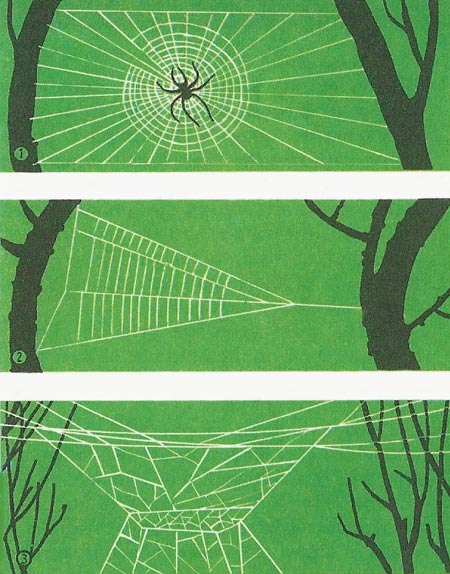

Figure 9. (Top) Zygiella spins an orb web with a gap in the spiral. (Middle) The triangular web of Hyptiotes. (Bottom) Hammock web of Linyphia montana.

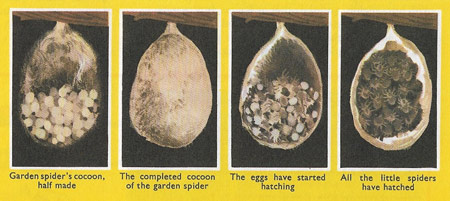

Figure 10. In the autumn the female garden spider lays her eggs in a sheltered place near her web, enclosing them in a silken bag or cocoon, and they remain there until early spring. The mother dies long before the little spiders hatch.

Spiders form the largest order of arachnids and are one of the most diverse groups of species in the world. About 35,000 species of spider are known. Each of us will encounter them in everyday life, and throughout history they have appeared in culture, mythology, and symbolism.

It would seem that the earliest spiders fed upon insects before the latter evolved wings, and caught them on the ground in the same way as present-day wolf spiders. The development of insect flight opened another niche for the spiders who countered with the evolution of webs and snares to capture flying prey. Insects became masters of the air, but spiders joined the "aerial plankton" (creatures that live hanging in air or blown on its currents), suspended on silk threads.

Chief characteristics

Spiders occur in a large range of sizes. The Patu digua, which is endemic to Columbia, is considered to be the smallest species of spider in the world, with males reaching a length of only 0.37 millimeter. The largest species of spider is the Goliath bird-eating spider, with a body length up to 9 centimeters (3.5 inches), a leg span up to 28 centimeters (11 inches), and a weight of over 170 grams (6 ounces).

Spiders come in a variety of colors and with a great diversity of markings. Some rely on camouflage in order to blend in with their background, while others are bright colored as warning that they are poisonous to predators.

For locomotion, spiders use hydraulic pressure. They can create pressure up to eight times that of their resting level pressure in order to extend their legs. Jumping spiders use this pressure to enable them to jump up to 50 times their own body length. Spiders that hunt their prey have dense tufts of fine hair, known as scapulae, on the tips of their legs, which enable them to move around on ceilings and walk vertically up a pane of glass. Whenever a spider is walking or running, it has at least four of its legs on the ground at all times.

|

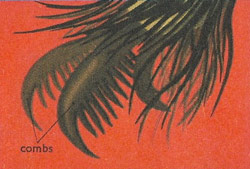

| The end of a spider's leg, greatly enlarged. Note the comb-like apparatus, which guides the web as it is spun. |

On its abdomen a spider has spinnerets which it uses to produce silk. Each spinneret has several spigots, and each of these is connected to a silk gland. There are at least six different types of silk gland and each one produces silk with different properties. Spider silk is mainly composed of a protein. Initially liquid, it hardens as it is drawn out of the silk gland. Spider silk is extremely strong, with a tensile strength similar to that of nylon, but has a much greater elasticity and can stretch much further before breaking or losing shape.

Most spiders have a life expectancy of 2 years, but some tarantulas that are kept in captivity can live for over 20 years.

External anatomy

The body of a spider is divided into two segments, separated by a narrow waist. At the front, the cephalothorax consists of a fused head and a thorax. Behind this is the abdomen. Spiders also have an endoskeleton and an exoskeleton; as the spider grows the exoskeleton is shed and replaced.

Most of the external appendages of the spider are attached to the cephalothorax, including the legs, eyes, pedipalps, and mouthparts. Spiders have eight legs and use specialized, sensitive hairs on their legs to detect scent, vibrations, sounds, and air currents. The pedipalps have coxae or maxillae at the base, just next to the mouth, which help with ingesting food. In males the end of the pedipalps are often modified into elaborate structures that are used for mating. Spiders are unable to chew their food and, instead, use a mouth part that is shaped like a straw to suck up the liquefied insides of their prey. However, spiders are able to eat their own silk, thus recycling the proteins needed for the production of new webs.

Spiders can have up to eight single lens eyes that are arranged in a variety of ways depending on the species. Several families of hunting spiders, for example wolf spiders and jumping spiders, have good vision with the main pair of eyes in jumping spider species having colored vision. Net-casting spiders have large compound lenses that enable them to have a good field of vision and gather light effectively. However, most species of spider have a poor sense of vision and rely mostly on their extreme sensitivity to vibrations to help them catch their prey.

The abdomen has no appendages except for 1–4 pairs of spinnerets used to produce silk, and, on the underside of the abdomen, two hardened plates, called epigastric plates, which cover the book lungs.

Internal anatomy

Spiders do not have true blood, or vessels to carry it around their body, but instead have what is known as an open circulatory system. Their body is filled with a substance called hemolymph which is pumped through arteries, by the heart, into spaces surrounding the internal organs called sinuses. The hemolymph contains a respiratory protein called hemocyanin, which is bluish in color due to the two copper atoms found its molecule. A spider's heart is just a simple tube, located in the abdomen above the intestine and close to the dorsal body wall. The aorta is at the anterior end of the heart and supplies hemolymph to the cephalothorax. Smaller arteries extend from the sides and posterior end of the heart. A thin-walled sac called the pericardium completely surrounds the heart and provides it with protection.

Spiders digest their food both internally and externally. Those species that lack strong chelicerae, secrete digestive fluid from a series of ducts onto their prey. The digestive fluids dissolve the prey's internal tissue, enabling the spider to feed by sucking up the partially digested fluid. Those species that have powerful chelicerae eat the entire body of their prey, aside from a small residue of indigestible material.

Spiders have developed several different respiratory systems, which are based either on book lungs or a tracheal system, or both. Some species have two pairs of book lungs, filled with hemolymph, which have openings on the ventral surface allowing air to enter and diffuse oxygen. Other species have only the anterior pair of book lungs, the posterior pair having been partly or fully modified into tracheae, through which oxygen is diffused into the hemolymph or into the tissue and organs directly. Yet other species have evolved the anterior pair of book lungs into trachea; or, the remaining book lungs may be very small or missing. Some very small species of spiders that inhabit moist, sheltered habitats have no respiratory organs at all, and instead breathe directly through their body surface.

Distribution and habitat

Spiders are found throughout the world, on every continent except Antarctica, and occur at elevations up to 5,000 meters (16,400 feet). They live in a wide range of habitats, although more species occur in the tropics than in temperate regions. They are mostly terrestrial, but there are some aquatic species that live in slow-moving freshwater habitats.

Spiders are generally solitary but some species build webs together and exhibit social behavior. The species Anelosimus eximius can form colonies that contain up to 50,000 individuals.

Reproduction

As male spiders are generally smaller than females, they have to perform an elaborate courtship ritual to prevent the female eating them prior to fertilization. The type of ritual depends on the species but can include a pattern of vibrations in the web, touching, gestures, and dances.

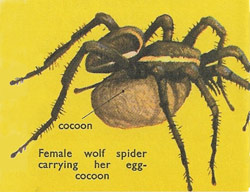

If the courtship is successful, reproduction follows with the female laying up to 3,000 eggs in silk egg sacs. In some species, the female dies at this point, but in others she protects her egg sacs by keeping them in their web, hiding them in a nest, or carrying them around.

|

| The wolf spider (Pisaura) lays her eggs in summer and carries the cocoon wherever she goes. When the eggs are about to hatch she puts the cocoon down, builds a silken tent over it, and guards it until her babies hatch and can go away on their own. |

Young spiders develop inside their egg and hatch as spiderlings. The young spiderlings are very small and sexually immature, but are otherwise similar to their adult form. In some species the spiderlings are left to fend for themselves, but in others are taken care of by the parent until they are older.

Diet and methods of capturing prey

Spiders are mainly carnivorous and their prey is usually insects, although some larger species have been known to eat birds, small mammals, and lizards. Some species also include pollen and nectar in their diet. Bagheera kiplingi, a species of jumping spider, feeds primarily on plant matter.

Using a sticky web is the most common method for spiders to capture their prey, and involves the spider building a web to trap insects that fly into it. Net-casting spiders spin only a small web but they manipulate it to capture their prey. Female bolas spiders build a web that consists of just a single line, which they patrol. They also make a bolas from a single thread with a very sticky ball of silk at the end, which they swing at their prey until the victim gets stuck to it.

Trapdoor spiders and many species of tarantula are ambush predators; they lie in wait in burrows then rush out and ambush their prey as it goes past. Once the prey has been captured, venomous spiders use their venom to kill it. Wolf spiders and jumping spiders are among the species that chase after their prey and rely mainly on vision to locate it.

Predators and defense

Among the chief predators of spiders are birds and parasitic wasps. Usually spiders rely on camouflage to evade their predators, or use warning coloration and threat displays to see them off. Some varieties, such as baboon spiders and tarantulas, have urticating hairs on their abdomen, and use their legs to flick these hairs at potential predators. The hairs cause intense irritation and put off predators from attacking.

Webs

Spiders build webs from proteinaceous silk which is produced by and extruded from spinnerets. They are not the only creatures that make silk in this way, silkworms and other caterpillars do as well. But a spider's life depends on its silk-spinning to such a degree that any study of it is largely a study of webs, and of all the other uses to which it puts its fine delicate silk which it spins. Most of the webs we see are made by female spiders; the male spends much of its time wandering in search of a mate. Webs are mainly used for catching prey; not all spiders build them. Among the types of spider webs are:

The spider that makes a web does so in order to catch the flying insects on which she feeds. She waits, either at the center or in a lair beside the web, whereabouts in the web it is entangled. As soon as one is caught she runs across the web to it and quickly bundles it up in a sort of parcel of silk. Then she kills it with a poisonous bite and sucks it dry. If a spider catches a dangerous insect like a wasp, she will deliberately cut the web and let it go.

Spiders may use several different types of silk when making their web, including a "sticky" or "fluffy" silk that helps to capture prey. Sheet webs are built on a horizontal plane and most orb webs on a vertical plane, but webs can be spun at any angle.

Spiders use their silk for many purposes besides the web. Some of them live in burrows, which they line with silk so they are watertight, and they may make a silken lid or trapdoor to the burrow. The jumping spiders live on walls and fences, and stalk flies as a cat stalks a bird. When one of these jumps on its prey, both fall, struggling together, but they do not fall far, for the spider never jumps without first dabbing down the end of a thread of silk strong enough to hold the weight of herself and her victim; when she has killed it she climbs up the thread again, carrying the fly with her. The little money spiders even use their silk to fly with. They climb to the top of a plant or bush and pay out thread just as the garden spider does when she makes her 'bridge line'. But the money spider's thread is caught by the wind, and when it is long enough the spider just lets go and blows away with it, perhaps for hundreds of miles, for they often land on ships at sea. Sometimes, in the autumn or late summer, these silken kites descend in huge quantities on the grass and bushes, and we call them gossamer.

There are many other types of web besides the wheel or orb web of, for example, the garden spider (Figure 9).

A Greek legend tells of a maiden called Arachne who fancied herself, with good reason, as a spinner. A contest was arranged between her and the Goddess of Wisdom, Athene, and the girl was unwise enough to win it. Athene was so furious that she turned the girl into a spider, doomed to spin on and on forever.

Taxonomy

All spiders belong to the order Araneae of which there are three recognized suborders: Mesothelae, Mygalomorphae, and Araneomorphae.

Spiders in the suborder Mesothelae are identified by having segmented plates on their abdomens. Relatively few species belong to this suborder and they have a limited geographical range, being found only in Southeast Asia, Japan, and China.

| Classification of spiders | |

|---|---|

| order | Aranae |

| class | Arachnida |

| subphylum | Chelicerata |

| phylum | Arthropoda |

| subkingdom | Metazoa |

| kingdom | Animalia |

Members of the suborder Mygalomorphae are identified by having fangs that point straight down and don't cross over each other. Spiders in this suborder are generally large, hairy, and heavily built. Well-known examples include tarantulas, Australasian funnel-web spiders, and trapdoor spiders.

Spiders in the suborder Araneomorphae make up over 90% of all spider species and include most varieties encountered in daily life. They have fangs that point diagonally forward and cross in a pinching action. Spiders in this suborder have the most diverse lifestyles. Familiar examples include wolf spiders, jumping spiders, and orb-web spiders.

The three suborders of spiders are further subdivided into 110 families, which in turn contain approximately 3,700 genera and over 40,000 living species.

Interesting facts