Alexander the Great

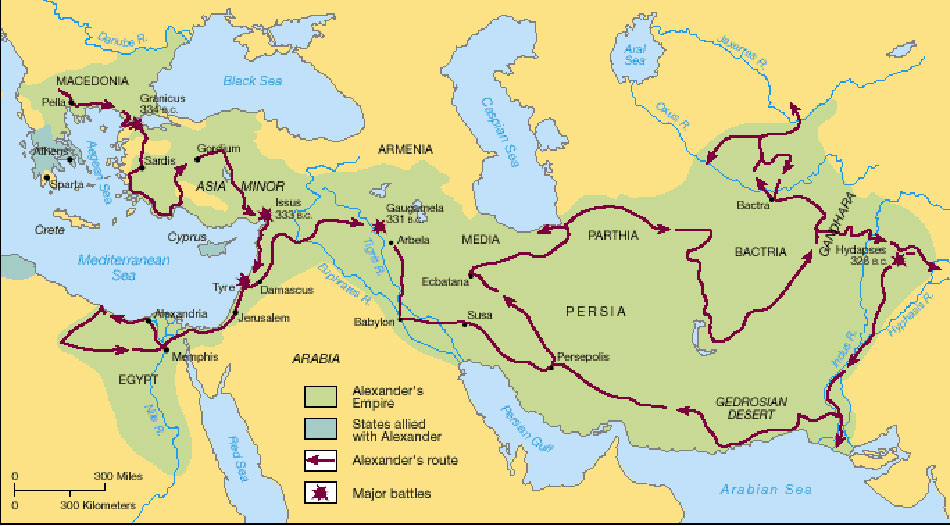

Figure 1. Map of Alexander's journey through the Persian Empire to India and back.

Figure 2. Alexander, as a boy of fourteen, tames the wild horse Bucephalus which no one else could master. He rode Bucephalus in all his battles, and when the horse died of wounds, in India, he built a town and named it after him.

Figure 3. This mosaic from Pompeii, copied from a painting by Philoxenus, shows Alexander commanding his army against the Persians, under Darius, at the Battle of the Issus, 333 BC. Darius fled, leaving his queen and family together with a vast amount of wealth to the Macedonians.

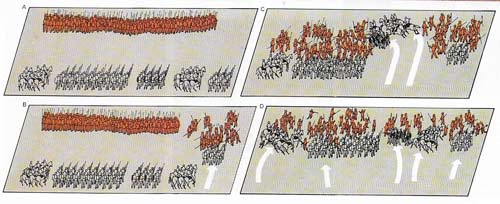

Figure 4. Alexander placed the phalanx at the center of his battle order (A). Fighting was initiated on the extreme right (B). At the right moment Alexander would lead his companions, supported by the household infantry, in a charge that penetrated the gap in the enemy line (C). As the enemy ranks broke, he wheeled his companions to take the flank to relieve the left and center of his army. As the enemy retreated, he pressed home his advantage with his full force (D).

Figure 5. Bust of Alexander.

Alexander, the son of Philip of Macedon and Olympia, princess of Epirus, was born at Pella in Macedon in 356 BC and died in Babylon in 323 BC. The pupil of the philosopher Aristotle between the ages of 13 and 16, he succeeded to the Macedonian throne in 336 BC on the assassination of his father, whose cavalry he had commanded two years earlier at the battle of Chaeronea (Figure 2).

The people of Macedonia, in northern Greece, lacked the education and refinery of the Athenians, but they were tough fighters. Philip had made his army intothe finest military force of the age and compelled the Greek states to accept him as ruler; Athens and Sparta were too exhausted by fighting each other to unite against Macedonia. The battle of Chaeronea finally ended Athenian hopes of regaining the leadership of Greece, giving hegemony to the Macedonians who were, at best, peripheral Greeks. It also marked the victory of the soldier over the rhetorician, for it had been Demosthenes, the Athenian orator (c. 383–322 BC), who had most attacked the Macedonians and their king.

Philip was planning an invasion of the great Persian empire, the ancient enemy of Greece, but he was murdered in 336 BC in a palace conspiracy, and Alexander became King at the age of twenty.

Securing the frontiers of Macedonia

During the next 13 years Alexander was to establish the greatest empire the ancient world had ever known (Figure 1), stretching from the Libyan frontier to the Punjab. His exploits gave rise to stories and legends in all the languages of Europe and many of those of Asia.

Upon his accession he marched south into Greece and, asserting Macedonian supremacy, had himself elected by the Greek League as a leader of an Asian expedition, one that had already been planned by his father. The oracle of Delphi hailed him as invincible. In 335 BC he campaigned towards the Danube, to secure Macedonia's northern frontier. On rumors of his death, a revolt broke out in Greece with the support of leading Athenians: Alexander marched south covering 386 km (240 miles) in a fortnight. When the revolt continued he sacked Thebes, killing 6,000 people and enslaving the survivors, sparing only the temples and the house of Pindar (c. 522–c. 440 BC), one of the greatest of Greek poets. His base thus secured, he prepared for the campaign for which his father had raised him. He also needed the riches of Persia to pay his father's debts to the Macedonian army.

The victory over Darius

Alexander crossed the Hellespont in 334 BC, with 30,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry and a corps of specialists. He paid a visit to Troy and at the River Granicus fought a battle that opened Asia Minor to his southward drive. He defeated Darius III, the Persian king (who fled, leaving his family), at the Issus (Figures 3 and 4) in 333 BC and continued until his advance was held up at Tyre, which fell in July 332 BC.

After the sack of Tyre, Alexander went to Egypt (which had been ruled by Persia for 200 years), where he founded the city of Alexandria. On visiting the shrine of Amon at Siwah Oasis, he was greeted as pharaoh, son of Ammon, an event that gave rise to stories of his divine origin. He also sent an expedition into Ethiopia to discover the source of the Nile and visited the desert temple of Zeus-Ammon, where the priests hailed him as the son of Zeus.

In 331 BC, he marched eastward to the Euphrates and fought another battle at Gaugamela, near Arbela (modern Erbil, in Iraq), but Darius once again escaped; Alexander received the surrender of Babylon and Susa with their riches. In 330 BC he captured Persepolis; then he sent the Thessalians and Greeks home, apparently planning a Persian-Macedonian empire. While he was campaigning eastward Darius was assassinated by his own officers.

Alexander next marched into Afghanistan and Transoxiana, partly to pursue a rebellious general, and thence to Samarkand and Alexandria Eschate (present-day Leninabad). There were further revolts until 328 BC, the year of his marriage to Roxana, daughter of the king of Bactria, a marriage that seems to have been symbolic of East-West fusion. At the same time his absolutism increased. His murder of his commander and friend Clitus in a drunken brawl angered the Macedonians.

In 327 BC he led his men into India, one army marching through the Khyber Pass while the other, which he commanded, fought its way through Swat. The final battle was fought on the Hydaspes (Jhelum); after the defeat of Porus, an Indian prince, Alexander's soldiers refused to go farther.

The distances Alexander covered are astonishing, especially in an age without maps; from Persepolis, the Persian capital, to the Caspian Sea; to remote Afghanistan and the inaccessible Hindu Kush; north again to Samarkand and Tashkent in Central Asia; then southeast to the Khyber Pass and into India.

|

| The battle of the Hydaspes (Jhelum) in the Punjab, shown here, on this coin, was one of Alexander's most skillfully planned and executed victories, greatly extending his empire. His tactics were greatly influenced by the horse's natural fear of the elephant. The defeated Indian ruler Porus became an ally. During this battle Alexander's famous charger Bucephalus died and was given a full imperial funeral. |

Return from the East

On his return to Susa, Alexander found a state of corruption and oppression. He set about a ruthless campaign of punishment. This was followed by a scheme for settling Greeks and Macedonians in Asia and Asians in Europe as part of a plan for fusing the two regions. A more immediate project was the marriage of Alexander and Hephaestion (his closest friend and lover) to two of the daughters of Darius, while another 80 Macedonian officers married daughters of Persian nobles.

Asian soldiers had already been trained in Macedonian military methods and were now admitted to the army; others were recruited to the cavalry and Persian officers to the royal bodyguard. In 324 BC his 10,000 Macedonians, already disturbed by the new army policy, mutinied. Alexander ordered 13 of their leaders to be killed on the spot, appointed more Persians and Medes to Macedonian posts and transferred regimental names to what the Europeans considered barbarian regiments. The Macedonians then set off on the return march.

Plans were now made for a campaign into Arabia, but Alexander developed fever and on 13 June 323 BC he died, not yet 33 years old. His empire began to disintegrate almost at once as the various regional commanders assumed the titles of kings in their own right. Although Alexander was renowned primarily for his military conquests, his most enduring achievement was to extend the influence of the Greeks to a vast area of the ancient world, and to widen the basis of Hellenic culture through contact with the East.