Britain 1930 to 1945

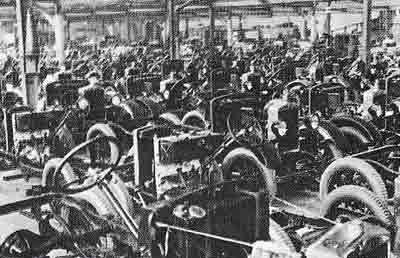

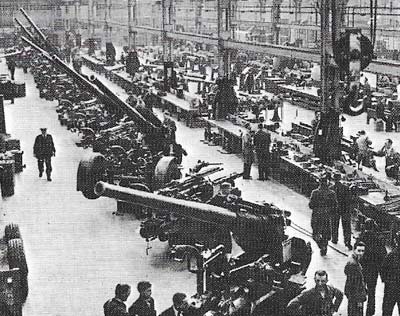

Figure 1. Mass production methods, pioneered in the United States, were adopted in Britain during the interwar years. They brought the first cheap motor vehicles within the reach of the middle classes. By 1939 there were nearly two million motor vehicles in Britain and the "motoring revolution" had begun. Car production for the home market increased each year up to the war, with the exception of 1932.

Figure 2. The communist-led National Unemployed Workers' Movement organized "hunger" marches on London on the thirties to protest about the plight of the unemployed. The marches however, had little effect on government policy.

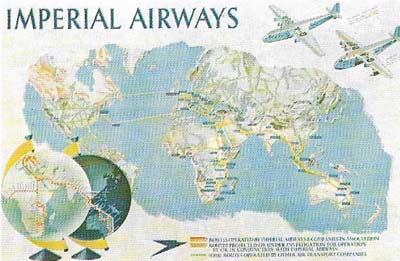

Figure 3. The thirties witnessed a rapid growth in commercial air transport and routes were set up across the world. Imperial Airways, a government-subsidized amalgamation of several privately-owned companies, was established in 1924. One of its main aims was to routes throughout the empire. Airmail was as important as passenger services; by 1938 Imperial Airways carried all first-class mail to the empire.

Figure 4. Private house building expanded greatly in the 1930s, and was a principal factor in the economic recovery during the last half of the decade. Despite government cuts in building programs, private investment in housing boomed, especially in the thriving regions of the Midlands and the southeast. Nearly three million houses were built between 1930 and 1939. This expansion in building led to a boom in other industries such as electrical and household goods.

Figure 5. The cinema was one of the most important forms of cheap mass entertainment in the 1930s.

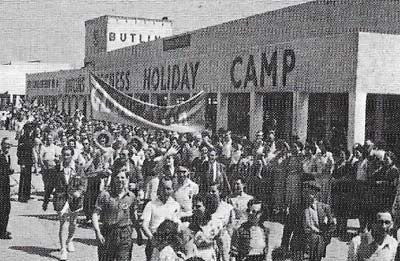

Figure 6. Rising living standards for those in work as well as a more widespread introduction of paid holidays contributed to a growth in holiday-making. The first holiday camps were opened in 1937.

Figure 7. Oswald Mosley's British Union of Fascists held many demonstrations and marches in the years before the war. Their use of uniforms and violent methods aroused widespread hostility, as did, more particularly, their antisemitism. In 1936 the Public Order Act was passed forbidding the use of uniforms and strengthening police powers against political demonstrations and mass meetings.

Figure 8. Britain was slow to rearm in the thirties. Limited rearmament was undertaken from 1934, mainly in the air force and navy, although German expenditure on arms was sometimes exaggerated. The government delayed thorough-going rearmament until after 1938 on the assumption that public opinion, as manifested in the Peace Ballot (a house-to-house poll) and by-election results, would not stand for sterner measures.

Figure 9. The immense war effort in Britain put eight million people into uniform in World War II. Over 300,000 members of the armed forces and, on the home front, about 60,000 civilians lost their lives in the conflict. In contrast with 1919, demobilization went relatively smoothly, although the Far and Middle East, British troops often became involved in local police-keeping and occupation duties, such as in Cyprus, that continued for some time after 1945.

Between 1930 and 1945 Britain experienced the deepest economic depression in its history and the massive mobilization of resources required for total war. In 1929, when a Labour government was elected under Ramsay MacDonald (1866–1937), Britain was already suffering from depression in its staple heavy industries: coal mining, iron and steel, textiles and shipbuilding.

Consequences of the Depression

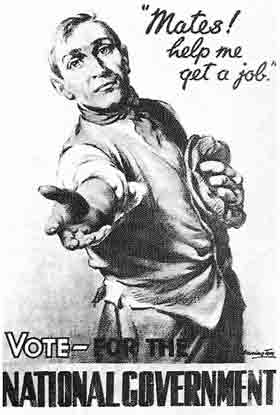

The Labour government was pledged to tackle the problem of unemployment, which stood at more than one million insured workers (Figure 2). No sooner was the government formed, however, than the Wall Street crash plunged the major western industrial economies into deeper depression. By 1931 the government was faced with more than two-and-a-half million unemployed and a heavy drain on its resources to meet the cost of unemployment benefits. The Labour government had little to offer as a solution to the economic depression. Radical voices, such' as that of Oswald Mosley (1896–1980), a junior member of the Labour government, and Lloyd George (1863–1945), leader of the Liberals, offered solutions along the lines later advocated by John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), but were ignored in the pursuit of orthodox economic policy. This dictated that the government should curtail its expenditure and raise business confidence in the hope that normal trading conditions would begin to reduce unemployment. The recommended cuts in expenditure included a reduction in unemployment benefit.

In 1931, the Labour cabinet was deeply divided over implementing the cuts. The government was forced to resign over the issue, but MacDonald and a group of Labour MPs joined with the Conservatives and Liberals to form a coalition, the National Government. A general election was then called, which led to a resounding victory for the new administration.

|

| Unemployment was the major issue of the early 1930s. In October 1931 the National government, formed the previous August, sought a mandate from the electorate for its economic policies - designed to deal with the Depression. Under Ramsey MacDonald, the ex-Labour premier, the National government campaigned for a restoration of business confidence and reduced unemployment. In a mood of deep national crisis, the electorate swung heavily towards the National candidates. Only 46 Labour MPs were returned, compared with 554 National government MPs. Every Labour ex-cabinet minister lost his seat, except George Lansbury (1859–1940). |

The National Government introduced cuts in government expenditure, especially in unemployment benefit and the pay of state employees such as teachers and civil servants. Gradually the coalition was converted into a Conservative administration which triumphed at the general election of 1935.

In spite of the absence of major economic initiatives from governments in office after 1931, the economic situation began to improve from 1933 onwards. Unemployment reached a peak of almost three million in the winter of 1932–1933 and remained at more than a million until the outbreak of war in 1939, but it was falling from 1933–1934. Revival was concentrated in a range of new industries such as electricity supply, motor vehicles (Figure 1), consumer durables and chemicals. These industries brought increased employment to the southeast and the Midlands, while the older industries of the "distressed" areas remained depressed and only slowly began to recover.

Political unrest and social change

The rise in prosperity in some areas helps to explain the failure of the extremist parties to obtain greater support before the war. Oswald Mosley (Figure 7) formed the British Union of Fascists in 1932, after leaving the Labour Party and adopted the style of continental fascist parties. The party espoused radical economic ideas but earned a reputation for violence and anti-semitism that cut it off from mass support.

The thirties witnessed the rise of new social patterns, with an enormous growth of suburban living, a housing boom (Figure 4), slum clearance, and ameliorative social legislation. Opportunities for leisure activities, such as the cinema (Figure 5) and dance halls, expanded and provided cheap entertainment. Another influential and inexpensive source of entertainment was the radio. The BBC broadcast hours of popular music daily and did much to enhance the reputations of some of the great dance bands of the 1930s. The rise of the football pools, with their lure of instant wealth, was another social phenomenon of the times.

|

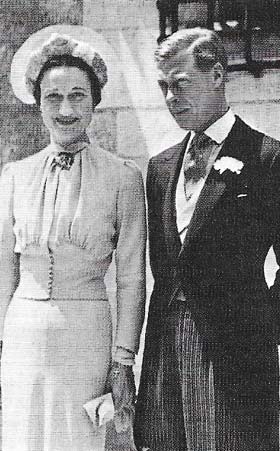

| Edward VIII (1894–1972), came to the throne on 20 January 1936 with considerable popular support, accumulated during his years as Prince of Wales. Public interest in his life showed the widespread devotion to the monarchy even during the worst years of the Depression. But the King's continuing relationship with an American divorcee Mrs Wallace Simpson (1896–1986), precipitated a constitutional crisis following her second divorce, in October 1936. The king wanted to marry her, but the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin (1867–1947), advised that she was unacceptable as a queen. In spite of considerable popular support for Edward, he abdicated in December. |

There was a profound distrust and loathing of war in the thirties. Peace movements flourished and the governments of Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain (1869–1940) pursued a policy of appeasing the dictators. But rising international tension led to gradual rearmament from the mid-1930s, helping to revive the economy.

The experiences of the Depression and thirties followed by total war helped to create a new mood in Britain. The Beveridge Report of 1942 advocated a high level of employment and the creation of a welfare state. Even before the end of the war, the Butler Education Act of 1944 made free secondary education available to all.

Postwar optimism

World War II witnessed an acceleration of many of the trends evident in British politics and society before 1939. The war further stimulated new industries as well as reviving the old ones, and led to widespread recognition of social problems such as poverty and unemployment. Widespread and vigorous debate about the nature of postwar British society paved the way for a Labour victory at the 1945 general election. The Labour government inherited considerable good will from the electorate. Demobilization caused far less resentment than it had in 1918 (Figure 9) and Labour's program seemed to meet the demand for new policies and an avoidance of mass unemployment.