British foreign policy from 1914

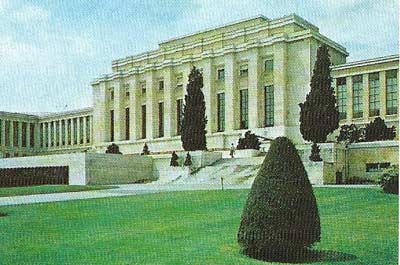

Figure 1. At the League of Nations, Geneva, in March 1925, Britain rejected a major attempt to enforce the peaceful settlement of international disputes in refusing to sign the Geneva Protocol. France sought to strengthen the league's powers of collective action against aggression by providing for compulsory arbitration of disputes. But Britain was wary of the protocol's absolute commitment to armed intervention.

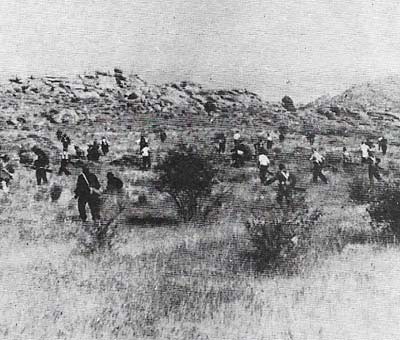

Figure 2. The Spanish Civil War was fought between the Nationalist rebels on the one hand, helped by Hitler and Mussolini, and the Spanish Republican Government on the other, from 1936 to 1939. The war seems to have presaged the later conflict waged between fascism and democracy in World War II. But in 1936, the British government was chief sponsor of an international agreement for non-intervention which was signed by all the major powers. This was adhered to by all countries except Italy, Germany, and the Soviet Union - the last-named sent to some aid to the Republican forces. Public opinion in Britain was divided: some, illegally, went to Spain to fight, mostly for the Republicans, whose British International Brigade numbered about 2,000 men.

Figure 3. British troops were sent to Korea in 1950 as part of the United Nations force to repel a North Korean communist invasion of South Korea. The UN force had been formed despite the opposition of the Soviet Union, which supported North Korea's claims to South Korea. At that time the cold war had reached its height and the UN was deeply divided by the East-West tensions that had emerged since 1945.

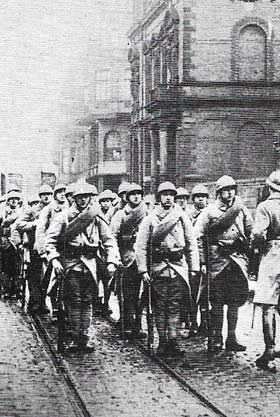

Figure 4. The nationalization of the Suez Canal in July 1956 by the Egyptian Government was part of a policy that aimed to unite the Arab world and end foreign control. Britain and France tried to internationalize the Canal and when this failed they attempted to seize the canal by armed force. The troops seen here were landed in November, but as a result of US pressure a ceasefire took place within two days. The incident was a major blow to the international prestige of Britain and France. Anthony Eden (1897–1977), the British prime minister, who had pressed for the use of force, resigned in the following January.

Figure 5. Ian Smith (1919–2007), Prime Minister of Rhodesia, unilaterally declared independence from Britain on 11 November 1965 after rejecting British terms for granting independence. Smith, shown here following discussions with British Prime Minister Harold Wilson in October 1965, wanted to maintain white supremacy in Rhodesia, although the white population was outnumbered 22 to 1 by black Africans.

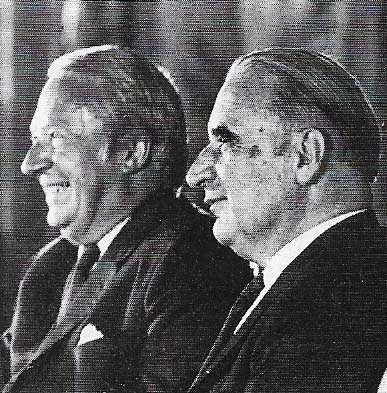

Figure 6. The leaders of France and Britain, Georges Pompidou (1911–1974) (right) and Edward Heath (1916–2005) (left) cleared the way for Britain to enter the EEC, in January 1973. When the Community was first formed in 1957 Britain refused to join, fearing the EEC's supranational powers. To subsequent applications for membership, in 1961 and 1967, were both blocked by Pompidou's predecessor, De Gaulle. Final talks had begun after De Gaulle's resignation, in 1969.

Figure 7. Anti-British feeling in Cyprus (1955–1960) typified the strains of decolonization in areas where Britain's handover of power after World War II was complicated by divisions in the local community. In other colonies, the transition to independence was often peaceful. But areas of violence included mandated Palestine, India, Egypt, Kenya, Malaya, and Aden.

Britain's aim in World War I (1914–1918) – to prevent the domination of Europe by any single power – was achieved by the peace treaties imposed in 1919 on Germany and its allies. But then the Allied coalition that won the war dissolved: the United States withdrew into isolation, Russia, under communist control, campaigned against the West, and France disagreed with Britain on the treatment of Germany. Between 1925 and 1930 British governments welcomed a short-lived reconciliation between France and Germany, helped by the flow of American money into Europe. But by 1931 the world was hit by a grave economic crisis.

|

| On 11 January 1923, French and Belgian forces, despite British protests, occupied the German industrial Ruhr (until August 1925) as a penalty for alleged non-payment by Germany of coal reparations. In the aftermath of World War I, Britain and France disagreed over the treatment of Germany. Britain, intent upon economic recovery, wanted Germany leniently treated; France demanded strict enforcement of the Treaty of Versailles. |

The age of appeasement

The economic slump propelled Adolf Hitler (1889–1945), leader of the National Socialists; into power in Germany in 1933 and ended the liberal regime in Japan. This provided Britain with two major foreign-policy problems in the 1930s: the satisfaction of German pressure for revision of the Treaty of Versailles 1919, especially its reparation and disarmament clauses, and the expansion of Japanese militarists into Manchuria, which they annexed in all but name in 1931–1932, and into China proper in 1933–1937.

Britain was handicapped in dealing with these problems by three factors: First its economic weakness, expressed in long-term unemployment; second, a public opinion stunned by the losses in World War I and nervous about rearmament; finally the sheer inability of Britain and France, with no help from isolationist America, to control Germany and Japan, as well as a restless Italy under Benito Mussolini (1883–1945).

|

| Winston Churchill was a backbench MP during the 1930s, and an outspoken critic of the National Government's policy of appeasement towards Germany. Public opinion favored a vague pacifism in the face of German rearmament and growing Italian and German aggression. Such was the desire for, if not faith in, peace that British rearmament did not seriously begin until after 1938. |

A confrontation became unavoidable after the Munich Agreement in September 1938. Britain and France thereby agreed to German occupation of the Sudetenland, which Was Czech territory accepting that this was Hitler's "final" demand; but on 15 March 1939 German forces cynically abrogated the agreement by taking over the rest of Czechoslovakia. Almost the only benefit derived by Britain from this short-sighted policy of appeasement was time to build up its pitiably weak defenses. When Hitler confidently invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, the British government finally honored their treaty obligations and declared war on Germany two days later.

|

| The Munich Agreement of 29 September 1938 typified Britain's policy of appeasement. Britain, France and Italy agreed that the Sudeten region of Czechoslovakia should be ceded to Germany. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain (1869–1940), shown here on his return from Munich, made an agreement with Hitler to consult on any future Anglo-German questions. A year later Britain and Germany were at war. |

Policy during World War II

After the collapse of France in June 1940, Britain faced Hitler's Europe alone. The military situation was transformed when Germany invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941 and when the United States entered the war after the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. But the diplomatic situation was complicated. The United States' President, Franklin Roosevelt (1882–1945) agreed with the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill (1874–1965) on general war aims in the Atlantic Charter, signed in August 1941, but had no interest in preserving the British Empire. At the Yalta conference (4–11 February 1945) the two met Soviet leader Joseph Stalin (1879–1953) and Roosevelt seemed to side with Stalin on imperial questions against the British.

Churchill, an old opponent of communism, willingly accepted Stalin's territorial claims in eastern Europe, but he was worried how far into western Europe Soviet influence would penetrate and whether the United States would help to resist it.

Loss of world power

Britain's Labour government of 1945–1951 hoped fervently for cooperation between the Soviet Union and the West after the war. But when the East-West cold war developed with disagreements about the revival of Germany and about Soviet communization of Eastern Europe, Labour ministers took Britain first into the Brussels collective defense pact of March 1948 with France and the Benelux states – Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg – and then into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), signed on 4 April 1949, with Canada, the United States and nine other states of Western Europe. At the same time, Britain received economic assistance from the United States through a £1,000 million loan in December 1945 and then through the Marshall Aid program of 1948–1952.

Britain strove continuously to moderate East-West tensions, by urging restraint on the United States during the cold war, but its credibility was undermined by recurrent balance-of-payments difficulties, and later by severe unemployment and inflation. These called into question the basic assumption of British policy after 1945: that Britain remained a world power, not with the strength of the United States or the Soviet Union, but still with an assured presence at conference "top tables".

|

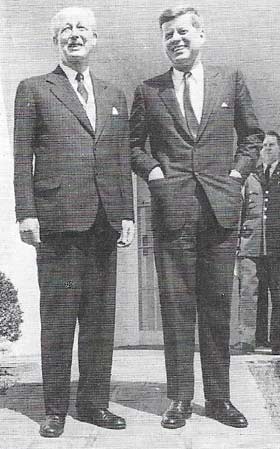

| The Anglo-American "special relationship" was a principal feature of British foreign policy after 1945. Two of its chief exponents were Harold McMillan (1894–1986) (left), British prime minister (1957–1963) and John F. Kennedy (1917–1963) (right), US President (1961–1963). Here they are shown after talks in Washington in 1961 that were aimed at controlling the spread of the H-bomb and increasing unity among the countries of the Western alliance. |

In January 1968 the Labour Prime Minister, Harold Wilson (1916–1995), decided to terminate the East-of-Suez role by December 1971, i.e., the maintenance of British forces in the Persian Gulf and at Singapore. The effect of this was to reduce Britain to the level of an essentially European and Mediterranean power.

The change in Britain's international position was symbolized in January 1973 by its entry into the European Economic Community. By that time Britain's empire, which once embraced a quarter of the world's population, had been gradually transformed into a loosely knit Commonwealth of politically independent states.