the Commonwealth

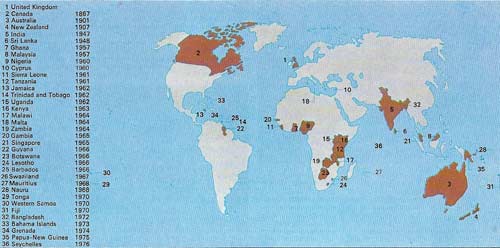

Figure 1. A quarter of the world's land surface is covered by the Commonwealth, which also embraces a huge number of languages and dialects as well as numerous religions. The feature common to all of the members is the historical accident of the settlement, annexation or conquest by Britain; and British institutions and the English language also remain important elements in the modern association. Since 1965, there has been a permanent central secretariat based in London. It organizes conferences and spreads information. But the Commonwealth has very little unity in international affairs. The dates of independence of each country are shown on the map.

Figure 2. The strong, moral leadership of Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948) lay behind much of the nationalistic agitation against the British in India after 1918. His asceticism, aura of holiness, and his use of fasting and passive resistance often embarrassed the British Government and actively involved the masses in India in the campaign for independence.

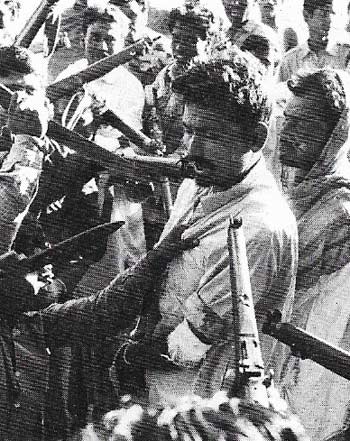

Figure 3. The character of colonial government varied in detail from one territory to another, but each was expected to follow much the same series of stages on the way to independence. And the advance, through responsible government, to dominion status by the old European colonies of settlement became the model. But in the final period of decolonization, the stages were not always as clearly defined as earlier.

Figure 4. Conflict – like this in Bangladesh – sometimes followed independence. National unity could be endangered and often parliamentary democracy was replaced by one-party rule and an autocratic president.

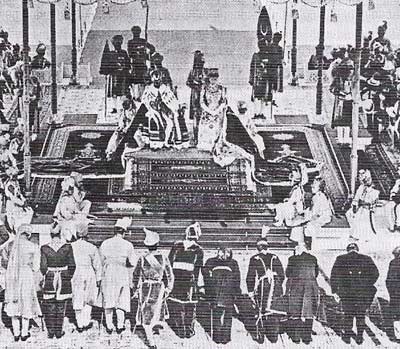

Figure 5. Until colonial territories in Africa and elsewhere became independent after World War II, the Commonwealth "family" – here assembled in 1926 – was a small, intimate group, all subscribing to British traditions and acknowledging one crown.

Figure 6. As membership of the Commonwealth grew, the informality of heads of government meetings became more difficult to maintain. But the members still felt that the meetings were valuable for the discussion of problems and improvement of mutual understanding. When other capitals (here Singapore in 1971) began to offer to be host, this further emphasized that the modern Commonwealth was no longer "British" but a unique, worldwide association representing many races, creeds and cultures.

Figure 7. George V was called "King of Great Britain, Ireland and the British Dominions beyond the Seas, and Emperor of India". His title illustrated the extent of his authority and also emphasized India's special position in the British Empire.

The Commonwealth (Figure 1) is a free association of nations comprising Great Britain and (in 1976) 35 other sovereign states that were once colonies or dependent territories within the British Empire.

The origins of the association go back to Britain's relations with her colonies of European settlement. For these she established during the nineteenth century a system in which they would acquire independence by stages (Figure 3). Crown government concentrated power in the governor and his council, which might be advisory or executive. Later there might also be a legislative council or assembly that lent itself to constitutional progress as the proportion of elected members grew in relation to the nominated members. Further advances would occur when the executive council, or government ministers, became responsible to the representative assembly, and when the indigenous council and assembly acquired powers of internal self-government over all but special and external matters. Finally these, too, would be won when full independence was granted.

Perhaps the first significant step in the transition from empire to commonwealth was a report by Lord Durham (1792–1840), in 1839, stating that one of the causes of contemporary unrest in the Canadian provinces was the lack of harmony between the executive and the legislature. The remedy, according to the report, was to choose executive ministers from the majority group in the representative assembly.

|

| Lord Durham's report in 1839 and the unrest in the Canadian provinces led to the introduction of responsible government in Canada and later in other colonies of settlement. This report opened the way for the development of independent parliamentary governments linked by a common allegiance to a single crown. |

From colonies to dominions

There were limitations on such local government: the management of foreign trade and relations, the disposal of unoccupied public lands and the amendment of constitutions remained with the British government.

These limitations were gradually removed, but that on the conduct of foreign relations remained until the twentieth century (by which time the self-governing colonies – Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Newfoundland – were known as "dominions"). The precise status of the dominions was undefined until a committee under Lord Balfour (1848–1930) produced a report (1926) which stated, "They are autonomous Communities within the British Empire, equal in status . . . although united by a common allegiance to the Crown, and freely associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations."

In those colonies that were not primarily of European settlement, constitutional advance was very much slower. In the 1930s colonial rule in Africa and Asia was assumed to have a long future ahead of it. World War II, however, helped to stimulate nationalist pressures, especially in India, which had already acquired some international recognition as a state. The struggle for independence in India had produced a number of powerful leaders, such as Mahatma Gandhi (Figure 2), who acquired worldwide fame for their defiance, of imperial authority, usually by non-violent resistance. In 1947 and 1948 independence was granted to India, Pakistan and Ceylon.

Nkrumah's "self-government now"

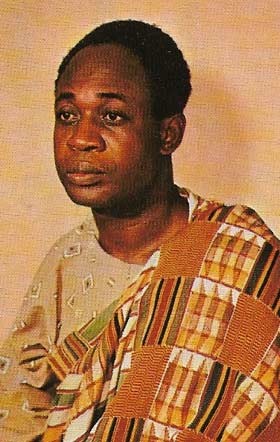

The concept of gradual progress was destroyed after Malaya and the Gold Coast became independent in 1957. In the Gold Coast, the nationalist leader Kwame Nkrumah, who became prime minister in 1952, refused to recognize any impediment to the early transfer of power, advocated positive action to cripple the forces of imperialism and popularized the slogan "self-government now". When the Gold Coast gained its independence, British Togo-land joined it to form the new nation of Ghana. In 1960 Ghana became a republic, with Nkrumah as president. The "wind of change" speech by the British prime minister Harold Macmillan (1894–1986) in 1960 reflected the new attitude of the British Government towards Africa.

|

| By campaigning strongly for "self-government now" in the Gold Coast, Nkrumah (1909–1972) helped destroy the concept of gradual transference of power in the restive African colonies. |

The newly independent countries chose to remain in the Commonwealth, despite the fact that they lacked the ethnic and common historical origins of the older members. They believed that their participation in the Commonwealth would bring them economic and diplomatic benefits and enhance their international influence. But they did not feel the special attachment to the monarchy that the older members had felt, and in 1949 India was the first state allowed to retain its membership as a republic while accepting the British monarch merely as the symbol of the free association of the members.

All members participate in the Commonwealth system of consultation and co-operation that covers a multitude of activities at governmental level. Periodically the heads of government meet (Figure 6) in conferences.

Expansion and the loosening of old bonds

Nevertheless, the old bonds of Commonwealth are not as strong as they used to be and much of the informal intimacy of earlier years has been lost as the association has expanded. Disillusionment with the Commonwealth was apparent among many members in the 1960s and 1970s – notably in Britain. The modern Commonwealth, however, continues to function as a flexible system of cooperation between states, enabling its member countries to confer with one another in an unusually frank, friendly and relaxed manner. As an association it represents the fulfillment both of the nationalist aspirations of colonial peoples and of a policy of constitutional evolution pursued by the imperial power.