Classical Greek society

Figure 1. The hub of Athenian democracy was the Pnyx where the Assembly of citizens gathered for its regular meetings. Public and social life was a gregarious and open-air affair with informal discussion, theatre and sports providing the most common interests.

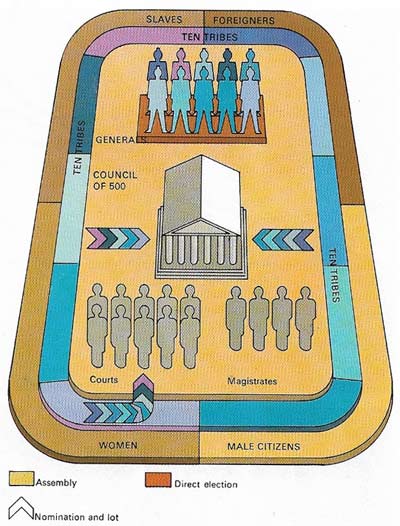

Figure 2. Fifth-century Athenian democracy was based upon the power of the Assembly of citizens to vote on all major decisions. Public officials were responsible to the Assembly and were chosen by the ten citizen tribes for limited terms; only the ten military commanders or strategoi were elected and could serve for more than a year. Popular control over both the magistrates and the law could also be exercised through the courts where the large citizen juries had legislative as well as judicial powers and could try a law as unconstitutional.

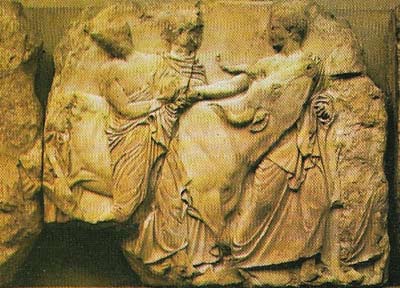

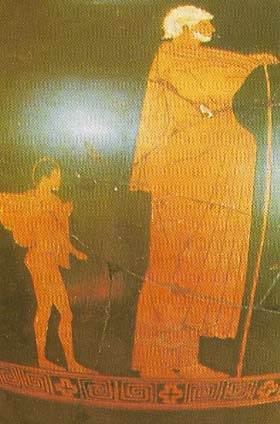

Figure 3. A heifer is led to sacrifice in a religious ceremony. Greek religion was supervised by the state – the correct prayers and sacrifices were carried out by elected priests or private individuals – but there was little of the moral certainty and interference in private affairs that characterized later religions. The gods were irrational and arbitrary and had to be placated, often by sacrifices; their conduct provided little guidance.

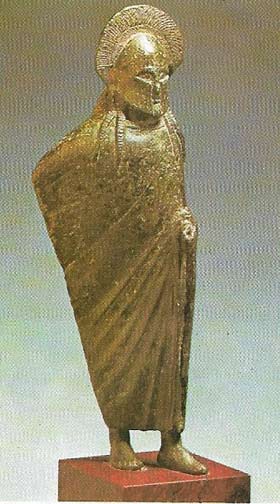

Figure 4. Women in Classical Greece were the other great "slave" class; they had no political or legal rights and were excluded from all public affairs. Their place was in the home with the children. Their absence from much social life led to widespread development of homosexual relationships and the institution of the hetaera – high-class courtesans outside conventional mores.

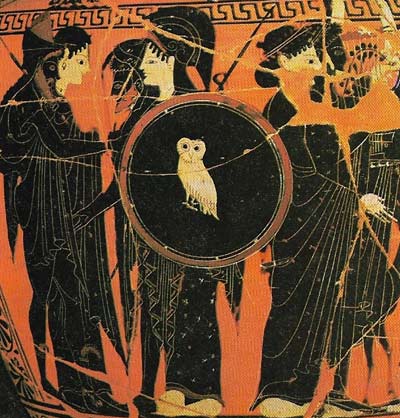

Figure 5. Gods and goddesses with Athena holding a shield inscribed with an owl are shown on this Greek vase. The pantheon was featured in the epics of Homer and was the basis of the religion of Classical Greece. The gods were conceived of in human form with human emotions. They often interfered in human activities and could be invoked or calmed by prayer and sacrifice. There was little belief in an afterlife; religion was strictly temporal, devoted to a pleasant existence.

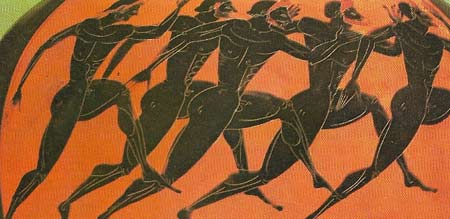

Figure 6. Athletic competitions and the cult of the well-trained and healthy body played an important part in everyday social life, the gymnasium or stadium being a popular meeting place where men could talk and hold political or philosophical discussions. The Greeks dated their history from the first Olympic games in 776 BC, a festival which, with contestants from all over the Greek world, provided an opportunity for Greeks to gather together as a nation.

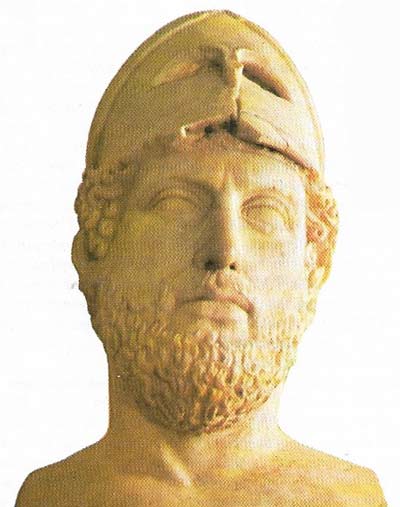

Figure 7. Pericles (c. 490-429 BC) was the great Athenian statesman under whose leader-ship the city became the richest and most powerful Greek state. He was responsible for the building of the fine temples and monuments on the Acropolis.

Classical Greece was the birthplace of many of the most influential Western ideas in art, literature, philosophy, and science. Its other great contribution was in politics, for it was there that the ideals of democracy were first developed. In all these areas Athens was pre-eminent, a fact recognized even by her contemporaries. In two centuries she produced a succession of outstanding writers, artists, scientists and philosophers. Many who were not natives were attracted to the city, and there are few important figures in Greek cultural life who were not associated with Athens for at least part of their careers.

Athens and democracy

The city state of Athens, with an area of about 2,500 square kilometers (1,000 square miles), was the largest of the many city states into which Greece was divided. Her population at its peak was about 260,000, of which about 45,000 were male citizens and about 70,000 slaves. The rest were women, children and resident foreigners or metics. Corinth may have had a population of 90,000; Thebes, Corcyra and Acragas about 50,000 each; and the other states anything down to 5,000.

Politics in all these city-states was a very intimate affair and this profoundly affected the Athenian concept of democracy (Figure 1). It was based on direct participation, rather than representation, with every citizen having an equal opportunity to hold high office. In common with many other Greek states, Athens went through the transition from oligarchy (a small number of individuals holding power) to tyranny (a single all-powerful ruler) with struggles between rich and poor before the reforms of Cleisthenes in 508 BC established a democratic framework.

The essence of this democracy was the citizen body or Demos. Citizenship was a jealously guarded right, rarely given to foreigners and never to women or slaves. All power was vested in the Demos which met in public assembly about every ten days (Figure 2). There, any citizen could put forward proposals for laws or action which were discussed and voted on, and the civil and religious officials were chosen. Juries were selected from volunteers, and the business of the Assembly was prepared by a Council of 500, the Bottle, elected by the ten tribes into which the citizens were divided.

Rights and duties

Every Athenian citizen had the right and duty to serve the state but, because there were more than 1,000 offices to be filled each year, the system could work only if there were enough men with both the time and inclination to devote their lives to public service. It is a remarkable fact that at no time was Athens short of able men to serve with little or no reward, and it was only during the fourth century BC that a small payment was introduced to help the poorest citizens to participate fully.

Athenians gained their wealth from land, trade and commerce. At the beginning of the fifth century Athens was a major exporter of pottery, oil and wine and an importer of fish, timber and wheat on which it was largely dependent. In Athens, in particular, a definite class of capitalists and an urban proletariat developed. Their leisure resulted from the widespread use of slaves to undertake many of the most basic jobs. Despite this influence of the wealthy, it is also remarkable that Athenian democracy saw few of the direct confrontations between rich and poor of the kind that caused continual unrest in most other city states.

|

| A Black African slave follows a member of the leisured class. Athenian democracy, with its large number of official jobs being filled by unpaid or low-paid citizens, depended on a plentiful supply of men with the inclination and leisure to undertake them. Athenian civic responsibility and pride in the system meant that there was never a lack of volunteers and this was helped by the wealth from land and commerce which flowed into the city. The large-scale use of slaves freed citizens for public service. Athenian thinkers saw no contradiction between the individual rights and freedoms on which their sys-tem was based and the slaves upon which it depended. |

All citizens and metics were liable for military service, but usually only the more wealthy were called up because troops were expected to equip themselves. By the early 7th century BC the typical Greek soldier was a heavily – and expensively – armed hoplite infantryman. At the height of the Peloponnesian war Athens put about 16,000 hoplites into the field; few other states could raise as many. In Athens the navy was especially important and had an intake of about 12,000 citizens a year.

|

| Spartan infantrymen (hoplites) were normally well and expensively equipped. The Spartan political system of a totally mobilized citizenry devoted to military service (boys were sent to barracks at the age of seven and not allowed other interests) was unique in Greece and gave Sparta far greater importance than its relatively small size justified. Most other states relied upon temporary conscription to fight the frequent wars that were endemic to Greek life. But a class of professional mercenaries did grow up during the 4th century, possibly as many as 50,000 in all, some fighting for the Persians. |

Sparta: a military state

No other state reached such a fully developed system of democracy as Athens. Its main rival for much of the period was Sparta, whose political and social system is remembered as representing the political opposite of everything that democracy stands for. By 600 BC Sparta had become a unique military state; Laconia and Messenia had been conquered and their populations either enslaved (helots) or deprived of political rights and forced to support the Spartans through taxation and food and manpower supplies.

To prevent revolt or secession, Sparta became a military camp. The citizen body was never large – probably never much more than 5,000 – but everyone was a professional soldier devoted from childhood to absolute discipline and the art of war. Two hereditary kings commanded the army in the field and were members of the ruling council of elders who were elected for life from citizens over 60. Five elected ephors had civil and judicial functions. No other Greek state approached Sparta in exclusiveness or xenophobia – even trade and commerce were largely disdained. A total refusal to admit new citizens led to a declining population and eventual defeat.

Sparta has remained the model of a closed and totally disciplined society, but it was Athens whose pursuit of individual freedom and democracy gave the modern world two of its most precious and lasting ideals.