current lag and lead

A current flowing around an electric circuit may meet with three different kinds of opposition or impedance. They are caused by resistance (R), inductance (L), and capacitance (C).

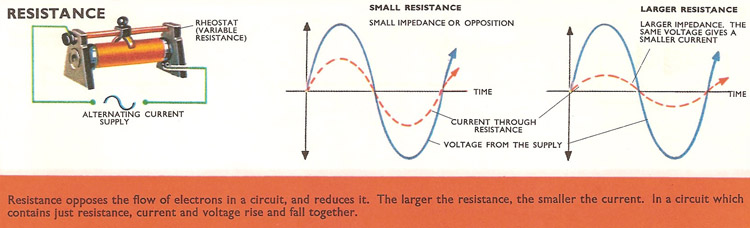

Of these, resistance is the easiest to understand, because it has the same effect on both direct currents and alternating currents. When the voltage across the two terminals of a resistance changes, the current changes immediately. If the voltage rises, the current rises; and if the voltage falls, the current falls, and so on. Current and voltage are said to be in phase.

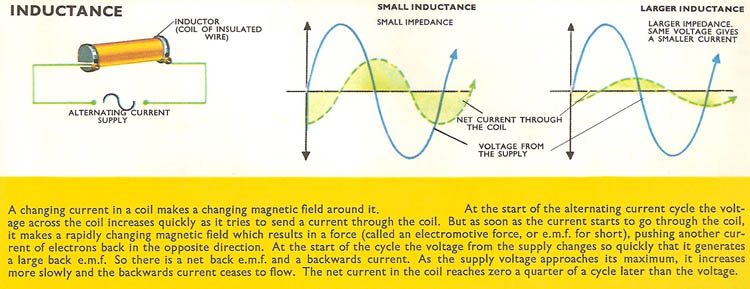

Inductors (L) and capacitors (C) behave quite differently. In 'L' circuits a rise in voltage is accompanied by a rise in current, but this rise is delayed by a back e.m.f. (see reactance) generated by the inductor. As the voltage rises and falls, the current rises and falls, but a fraction of a second later. So the current flowing through the inductor is always lagging behind the voltage, and current and voltage are said to be out of phase.

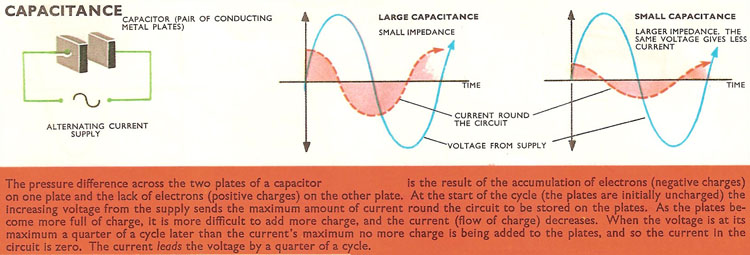

In 'C' circuits, on the other hand, the current in the circuit must first flow to the two plates of the capacitor (round the circuit from plate to plate and not across the gap between the plates) to make a potential difference across them. As the current rises, the voltage between the two plates rises; and as the current falls, the voltage falls, but the voltage follows the current's lead a fraction of a second later. Current and voltage are again out of phase, only in 'C' circuits the current is always leading the voltage.

One complete cycle of an alternating current consists of a rise (in current or voltage) up to the positive maximum, followed by a drop, through zero, to the negative maximum voltage, and a subsequent rise back to the zero starting point. A 'positive' current means that electrons flow in one direction round the circuit, while a 'negative' current means that they surge round in the opposite direction.

In a circuit containing only resistance, the positive surges of current and the positive increases in voltage coincide. But in a circuit containing only capacitance the surges of current occur a quarter of a cycle before the increase of voltage across the capacitance. In a circuit containing only inductance the current surges occur a quarter of a cycle later.

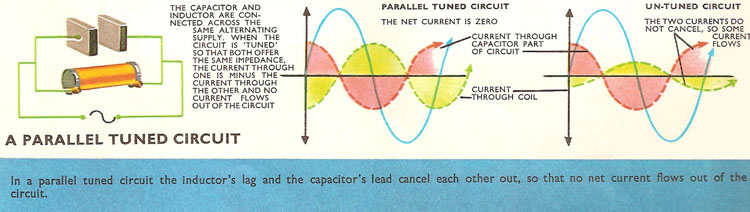

Suppose a capacitor and an inductor are both connected across an alternating voltage supply (i.e., connected in parallel), then the same voltage sends a current through each. But in the 'C' part of the circuit the current leads the voltage and in the 'L' part the current lags behind the voltage. If the values of inductance and capacitance are selected so that both offer the same impedance at the frequency of the alternating current supply, then the current through both 'L' and 'C' parts will be equal. But since one is a quarter of a cycle behind the voltage, and the other is a quarter of a cycle in front of the voltage, there is a difference of phase of a half cycle between the currents in the 'L' and 'C' parts. As one current is positive, the other current is negative (i.e., flowing in the opposite direction) and the same size as the positive current. So the two currents cancel each other out, and as a result no current flows out of the 'L' and 'C' combination, although there is a voltage connected across the pair of them. So the inductor-capacitor pair offers a very large impedance to the current – far larger than their separate impedances.

An arrangement called a parallel tuned circuit or rejector circuit will not allow through current of a particular frequency – the frequency at which the impedance of the capacitor is equal to the impedance of the inductor. Then the currents flowing through both parts are equal and opposite in direction. At any other frequency the two impedances will not be quite equal, the two currents will not be quite cancel each other out, and some current will be able to flow right round the circuit.