femur

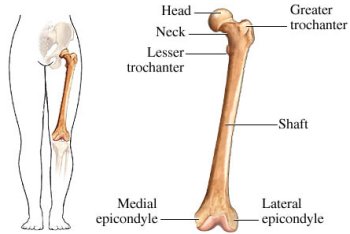

The femur, or thigh bone, extends from the hip to the knee of four- and two-legged vertebrates, including humans. It is the largest, longest, and strongest bone of the human skeleton. Its rounded, smooth head fits into a socket in the pelvis called the acetabulum to form the hip joint (an example of a ball-and-socket joint). The head of the femur is joined to the bone shaft by a narrow piece of bone known as the neck of the femur. The neck of the femur is a point of structural weakness and a common fracture site. The lower end of the femur hinges with the tibia (shinbone) to form the knee joint.

The femur can be felt through the skin at two sites. At the lower end, the bone is enlarged to form two lumps called the condyles that distribute the weight-bearing load on the knee joint. On the outer side of the upper end of the femur is a protuberance called the greater trochanter. The gluteus and psoas muscles are inserted on the greater and lesser trochanter, respectively. The lateral and medial epicondyles articulate with the tibia and the trochlear groove accommodates the patella (kneecap).

The term "femoral" means relating to the femur or to the thigh, as in femoral artery or femoral nerve.

Fracture of the femur

The symptoms, treatment, and possible complications of a fracture of the femur depend on whether the bone has broken across its neck or across the shaft.

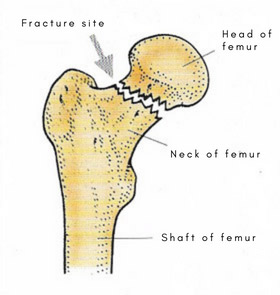

Fracture of the neck of the femur

|

| The neck of the femur is a common site of fracture in older people, often following a fall. |

This type of fracture, often called a broken hip, is commonly in elderly people, especially in women suffering from osteoporosis and is usually associated with a fall. This incidence of this type of fracture doubles approximately every seven years after the age of 65, so that by the age of 90 one woman in four has suffered this type of fracture.

In a fracture of the neck of the femur, the broken bone ends are often considerably displaced; in such cases there is usually severe pain in the hip and groin (made worse by movement) and the leg cannot bear any weight. Occasionally, the broken ends of the bone become impacted (wedged together). In this case there is less pain and walking is often still possible, which may delay reporting of the injury and detection of the fracture.

Diagnosis

and treatment

Diagnosis of a suspected fracture is confirmed by X-ray. If the bone ends are displaced, and operation under general anesthesia is necessary, either to realign the bone ends (a procedure called reduction) and to fasten them together with metal screws, plates, or nails, or to replace the entire head and neck of the femur with a metal or plastic substitute (hip replacement). Both procedures produce a stable repair, and hip and knee movement can be resumed immediately.

If the bone ends are impacted, the person is kept in bed for a few weeks to prevent any jarring movement that might dislodge the bones. The fracture heals naturally without surgery, but supervised exercise is necessary to maintain hip and knee mobility. X-rays are taken periodically to determine how well the fracture is healing.

With either type of repair, walking is started with the aid of crutches, progresses to walking with a walking frame, walking with a stick, and, finally, without aid.

Fracture of the shaft of the femur

This type of fracture usually occurs when the femur is subjected to extreme force, such as in a road traffic accident. In most cases, the bone ends are considerably displaced, causing severe pain, tenderness, and swelling.

Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnosis of this injury is confirmed by X-ray. With a fractured femoral shaft there is often substantial blood loss from the bone. In most cases, the fracture is repaired by an operation (under general anesthesia) in which the two ends of the bone are realigned and fastened together with a long metal pin. However, sometimes the bone ends can be realigned by manipulation, and surgery is not necessary. After realignment of the bones, the leg is supported with a splint and put in traction to hold the bone together correctly while it heals.

Following both types of treatment, supervised exercise and massage of the knee, ankle, and foot is started to prevent the joints from becoming stiff. The progress of healing is checked regularly by X-rays; when it is complete, weight bearing and walking is gradually started.

Complications

These include failure of the bone ends to unite or successful fusion of the bone ends at the wrong angle, infection of the bone, or damage to a nerve or artery. All of these complications usually require further surgery. A fracture of the lower end of the shaft can result in permanent stiffness of the knee.