Hobbes, Thomas (1588–1679)

Thomas Hobbes.

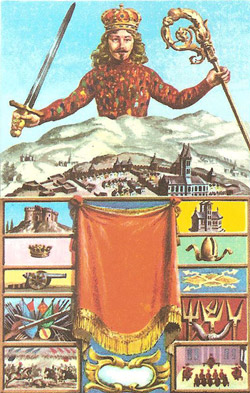

Frontpiece for Hobbes' Leviathan.

Thomas Hobbes was an English political philosopher who sought to apply rational principles to the science of human nature. In both the physical and the moral sciences reasoning was to proceed from cause to effect: certain knowledge could only flow from deductive reasoning upon known principles. Hobbes' view of man was materialistic and pessimistic – human actions were motivated solely by self-centered desires. This led Hobbes to consider that the existence of a sovereign authority in a state was the only way to guarantee its stability. Leviathan (1651), which gave voice to this opinion, was his most celebrated work. Hobbes saw matter in motion to be the only reality: even consciousness and thought were but the outworkings of the motion of atoms in the brain. During and after his lifetime, Hobbes was well known as a materialist and suspected as an atheist, but after the 19th century his fame as an able thinker overshadowed his former notoriety.

Biographical notes

Hobbes was born in the year of the Armada, at Malmesbury, Wiltshire – an ancient town which still contains some of the building young Thomas must have known. In school he excelled at both classics and mathematics. Before he left school to go to Oxford he had translated Euripides' play Medea from Greek verse into Latin. Because of his shock of black hair his schoolfellows nicknamed him the "Crow."

At Oxford he went to Magdalen College, where he took his degree, and after that he became a tutor in noble households and occasionally took his young pupils abroad. But in 1642 Hobbes, now well into middle age, suddenly decided to leave England.

At this time the personal government of Charles I was being strongly attacked by Parliament. This quarrel was to lead to the great Civil War of 1642–1647. The very thought of civil strife seems to have disturbed Hobbes. He had already become known as a supporter of the King's methods of government, and when another such supporter, Bishop Manwaring of St. David's, was imprisoned by the Parliamentary leaders, Hobbes thought: "tis time now for me to shift for my selfe," and that is why he went off to Paris.

There he added to his wide knowledge of other subjects by a study of chemistry and anatomy; but his real work – the work for which he was to become famous – was quite different. The Leviathan was for 200 years to influence thinking about politics.

John Aubrey, who later in the century wrote an amusing short life of the philosopher, has described Hobbes' way of working on this book. "He walked much and contemplated, and he had in the head of his staffe a pen and ink-horne, carried always a note booke in his pocket, and as soon as a thought darted, he presently entred it into his booke, or otherwise he might perhaps have lost it."

The book was finished in 1651, after the execution of Charles I, and was printed in London. Hobbes presented Charles II, who was in exile in Paris, with a specially bund copy, and then himself returned to England. Until the Restoration of Charles II he was allowed to live in London. By 1660, when Charles returned, he was an old man. He was still for of life, however, and the new King evidently liked his company, called him "the bear." "Here comes the beare to be bayted," said Charles when he saw him.

Hobbes died at Chatsworth in Derbyshire, the home of his first pupil, the Earl of Devonshire.

His great work

Hobbes' Leviathan is in some ways a rather depressing book to read, because he had a low view of human nature. However, it does reflect Hobbes' own experience and the violent history of his times. Hobbes himself hated conflict and always tried to avoid it. That was why he had gone to France in 1642. He thought it was better to live under a tyrant than in a land where law and order were liable to disappear. And this is the main theme of Leviathan. If left to their own devices, Hobbes says, men live in a perpetual state of war. Everyone is fighting each other, so the life of man is "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short". Since no one really wants to live like this, men, he says, should agree together to give up the freedom which produces all this conflict in return for the peace and quiet which a strong government can give. But it is no good men giving up half their freedom. If they do this, they will demand it back when their interests are threatened and society will be in just as bad a state as it was at the beginning. No, they must abandon all their freedom. Above all, they must give the government the right to carry out its will by force – by the sword. "Covenants without the sword," writes Hobbes, "are but words."

Tyrannical government

Hobbes is saying, in short, that it is better to live under a tyranny than in a state of anarchy (that is, no-rule). He does not seem to think that there might be a perfectly reasonable state in between. But then we must remember that he had seen a government, which did not have enough power to put its commands into effect, fall to nothing. He had lived through the execution of the English King in 1649, and the difficult times that followed that execution, when the only effective government seemed to be that of the army. It is not surprising, perhaps, that in a book describing the best form of government Hobbes should have insisted that it should be strong, well-armed, and able to crush opposition. It was the growth of opposition, we must remember, that had first made Thomas Hobbes runaway to France. Fear, he thought, was the dominating emotion of man. It was this depressing idea which made Hobbes so anxious to deprive men of the freedom they had.