phlogiston theory

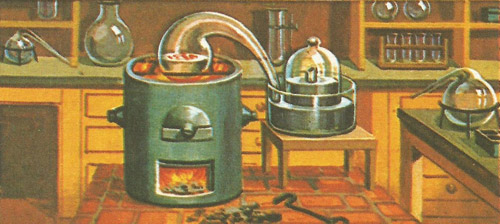

Lavoisier's apparatus for the famous experiment in which he showed the importance of oxygen in the burning process.

In the late 17th and mid-18th centuries, chemical theorists used the phlogiston theory to explain burning and rusting. They believed that every combustible substance contained the element of phlogiston, and the liberation of this hypothetical elastic fluid caused burning. The ash or reside that remains after burning was believed to be a dephlogisticated substance.

German alchemist and physician Johann Joachim Becher (1635–1682) initiated the theory of combustion that came to be associated with phlogiston. In his book Physica subterranea, published in 1669, he suggested that instead of the classical elements of earth, air, water, and fire, bodies were made from three forms of earth: terra lapidea (vitreous), terra mercurialis (mercurial), and terra pinguis (fatty). He thought combustible substances were rich in terra pinguis, a combustible earth liberated when a substance burned. For him, wood was a combination of terra pinguis and wood ashes.

Becher's theory of combustion influenced German chemist Georg Stahl (1660–1734), who gave the hypothetical substance terra pinguis the name "phlogiston", derived from the Greek word phlogizein, meaning "set alight". He believed there was a link between the processes of burning and rusting. Stahl was correct in the each process depends on a chemical process with oxygen known as oxidization. However, problems arose because rusty iron weighs more than unrusted iron and ash weighs less than the original burned object. The phlogiston theory of combustion found general acceptance until displaced by its inverse – Lavoisier's oxygen theory.

Phlogiston theory

The mysterious essence known as phlogiston was believed to be mixed with wood, coal, paper, and so on – in fact all substances that can be burned. If a fuel is weighed before burning and the ash left after burning it appears to have become lighter during the process. Early scientists thought that the phlogiston had disappeared during the burning, leaving only ashes. (It is now known that a fuel appears to become lighter only when some of the products of burning escape as gases. The total weight of ash and gases is always greater than the weight of the original fuel.)

Overthrow of the theory

It was, however, becoming apparent that the phlogiston theory of burning did not provide a really adequate explanation of the facts. The credit for its final overthrow can be given to the French chemist Antoine Lavoisier. Some years beforehand, Scheele and Priestley had discovered oxygen, though they had not explained what it was or what functions it performed. Lavoisier, in a series of important experiments, showed that air is made up mainly of oxygen and nitrogen gases and that oxygen plays a vital part in the burning process.

The most famous of Lavoisier's experiments involved heating mercury. The chemist put four ounces of mercury into a retort. A tube from the retort was passed to an airtight jar placed in a trough of mercury to seal it off. The retort was heated by a small furnace, and soon Lavoisier noted that a small red scales were beginning to form on the surface of the mercury in the retort. This was a sign that the chemical changes of combustion were taking place. Some of the mercury was combining with the oxygen to produce mercuric oxide (the red scales).

After twelve days it was found that no more scales were being formed. The burning process was complete. About a fifth of the air in the retort had been used up, though only a little of the mercury had disappeared. Lavoisier realized that the used up gas (oxygen) had combined with the mercury. The gas which was left (now called nitrogen) did not combine and remained unaltered throughout.

The second part of Lavoisier's experiment confirmed his idea on the part played by oxygen in burning. He removed the red scales from the mercury and placed them carefully in another retort. He then heated them (to a higher temperature than in the first part of the experiment). The result was that the mercury and oxygen in the scales (mercuric oxide) separated out once more. Measuring the weights of mercury and oxygen Lavoisier found that they were exactly the same as had been 'lost' before. By a happy accident the chemist had used a substance (mercury) where this chemical change could be reversed.

The conclusions reached by Lavoisier as a result of these experiments were, first, that oxygen makes up about a fifth of the air, secondly that it plays a vital part in the burning process, actually combining with the substance being burnt, and thirdly that the rest of the air (nitrogen) does not act in this way.