Shostakovich, Dmitri (1906–1975)

Shostakovich in 1950.

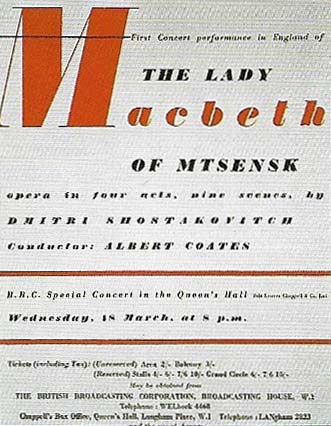

A program for the first London concert performance of Shostakovich's opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, in 1935.

Together with Stravinsky and Prokofiev, Shostakovich was one of the greatest Russian composers of the 20th century. His 15 symphonies and 15 string quartets are among the finest 20th-century works in those media.

Shostakovich began to learn the piano with his mother, a professional pianist. In 1919, aged only 13, he entered the St Petersburg Conservatory to study piano and composition: his teachers there included Glazunov. A phenomenally gifted student, his First Symphony (written as a diploma exercise) won international acclaim after its premieres in Leningrad (1926), Berlin (under Bruno Walter), and Philadelphia (under Leopold Stokowski); a year later Shostakovich received an honorable mention as an entrant in the International Chopin Piano Competition.

During the 1920s Shostakovich – a firm adherent to Socialist ideals – concentrated on stage and film music. An opera, Nos (The Nose), and two ballets, Zolotoy vek (The Golden Age, 1927–1930) and Bolt (1930–1931), showed him developing a brittle, witty, and satirical style which owed much to current European avant-garde influences, and for several years he was regarded as the "great white hope" of Soviet music.

Denunciation

Then came catastrophe. His opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, a savage tale of adultery, murder, and retribution, was produced in Moscow in 1934. At first it won critical acceptance both within Russia and abroad. But Stalin went to see it and was shocked by its graphic portrayal of sex and violence, and by its "advanced" musical idiom. On his orders, Shostakovich was savagely attacked in the press in 1936, in an article entitled "Chaos instead of Music".

Denounced also by his fellow composers, Shostakovich hurriedly withdrew the score of his Fourth Symphony, then in rehearsal, and responded with the more "accessible" Fifth Symphony (1937), which he described as "A Soviet artist's response to just criticism". For a while he appeared to have been forgiven: the Fifth Symphony proved popular, his 1940 Piano Quintet received the Stalin Prize, and his Seventh Symphony, written during the German siege of Leningrad in 1941, became an international symbol of heroic resistance (even though its repetitive "invasion" theme was cruelly parodied by Bartok in his Concerto for Orchestra, written in America in 1943).

Shostakovich's next two symphonies were also inspired by the war: the Eighth (1943) by its savagery, and the Ninth (1945) in a spirit of rejoicing at its end. But in 1948 he was once again officially denounced (together with Prokofiev and others), accused of "formalist perversions" and "anti-democratic tendencies in music". Such denunciations, during the Stalinist purges of the late 1940s, were tantamount to a death sentence, and if Shostakovich's posthumously published Memoirs are to be believed, from then until Stalin's death in 1953 he lived in fear for his life. He kept his private artistic credo alive with intimate chamber works, while publicly he concentrated on "safe" works based on nationalistic themes.

The post-Stalin era

After Stalin's death, Shostakovich returned to symphonic writing with the Tenth, Eleventh (The Year 1905) and Twelfth (The Year 1917) Symphonies. The late 1950s also produced the satirical musical comedy Cheryomuschki (The Cherry Trees Estate, 1958), a suite, The Gadfly, from his film score of 1955, the Second Piano Concerto (written in 1957 for his son Maxim, who became a well-known conductor), the First Cello Concerto (written in 1959 for Rostropovich), and the Seventh and Eighth String Quartets (1960).

In 1962 Lady Macbeth was restored to the Russian repertoire (under the new title Katerina Ismailova) and hailed as a masterpiece. Shostakovich then produced another controversial work, the Thirteenth Symphony (Babi Yar), based on poems by the Jewish writer Yevgeny Yevtushenko (born 1933). Its two successors, particularly the anguished Fourteenth Symphony of 1969 (settings of 11 poems by European writers), are preoccupied with death: the Fifteenth Symphony (1971), with its ironic references to other composers, seems to sum up Shostakovich's own career. The last decade of his life produced seven more string quartets, sonatas for violin and viola, and a further concerto each for violin and cello.

Towards the end of his life, Shostakovich was allowed to visit the West. He became a friend of Benjamin Britten, to whom the Fourteenth Symphony is dedicated. Like Britten, he died of heart failure in his 60s.