balloon

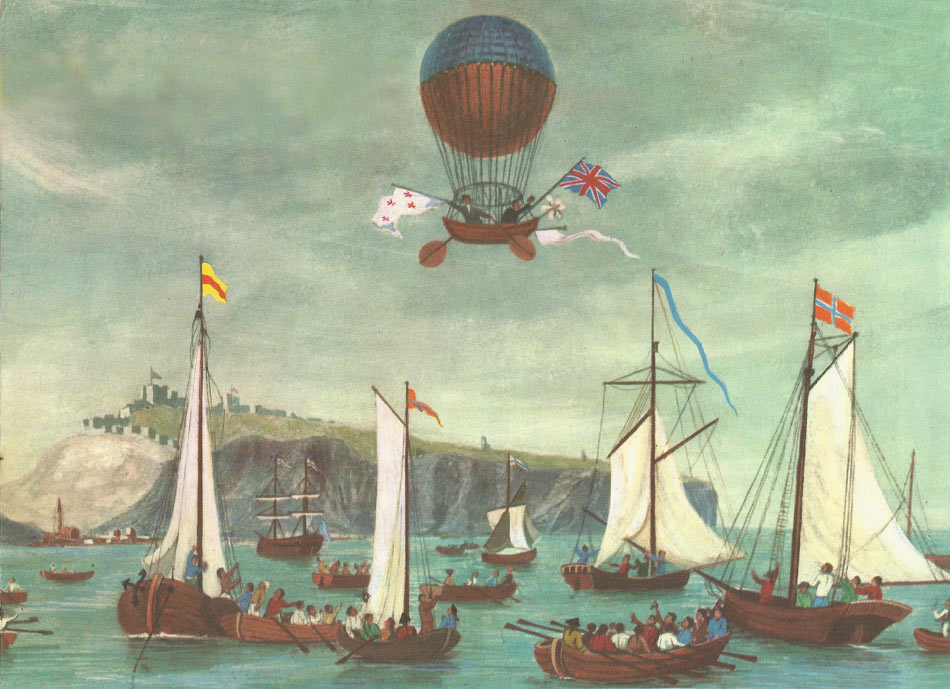

Blanchard and Jefferies departing from Dover Castle on 7 January 1785, to cross the English Channel by air for the first time.

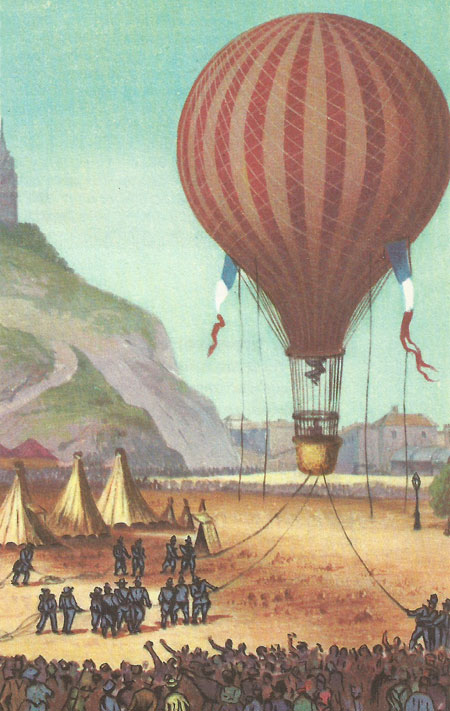

A captive balloon at Montmartre during the Franco-Prussian war.

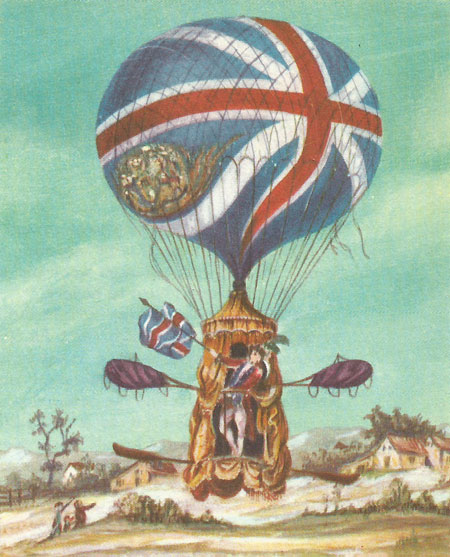

Vincent Lunardi's second balloon: 1785. (From the painting by J. Dighton).

A balloon is an unpowered, nonrigid, lighter-than-air craft comprising a bulbous envelope containing the lifting medium and a payload-carrying basket or gondola suspended below. Balloons may be captive (secured to the ground by a cable, as in the barrage balloons used during World War II to protect key installations and cities from low-level bombing) or free-flying (blown along and steered at the mercy of the wind). Lift may be provided either by a gas (usually hydrogen and noninflammable helium) or by heating the air in the envelope. A balloon rises or descends through the air until it reaches a level at which it is in equilibrium in accordance with Archimedes' principle. In this situation the total weight of the balloon and payload is equal to that of the volume of air which it is displacing.

If the pilot of a gas balloon wishes to ascend, he throws ballast (usually sand) over the side, thus reducing the overall density of the craft; to descend he releases some of the lifting gas through a small valve in the envelope. The altitude of a hot-air balloon is controlled using the propane burner which heats the air; increased heat causes the craft to rise; turning off the burner gives a period of level flight followed by a slow descent as the trapped air cools.

It is a far cry from the hot-air balloon of the Montgolfier brothers, sent up, on 5 June 1783, to Echo 1, a plastic balloon put into orbit at an altitude of 1,000 miles by the United States from Cape Canaveral in 1960. In size there was little between them. The Montgolfier balloon was 105 feet in circumference; it was made to rise by hot air from a fire made of small bundles of chopped straw over which it was placed. Echo 1 was 100 feet in circumference. Weighing only 6 pounds, it sped round the world twelve times a day at 15,000 mph. To prove that a satellite balloon could be used for world-wide telephone, wireless, and television communications, it bounced back by radio a recorded message of President Eisenhower.

In due course the powered balloon, or airship, was developed, though free balloons have remained popular for sporting, military, and scientific purposes. The upper atmosphere has been explored using unmanned gas balloons, and radiosonde balloons are in regular meteorological use. In 1931 Auguste Piccard pioneered high-altitude manned flights. The Montgolfier balloon was the first practical one.

Early balloon flights

The idea of a balloon, always an ambition of man, was probably inspired by the sight of floating clouds. In 1670 Francisco Lana had suggested that a lifting force might be obtained from four copper spheres from which the air had been expelled, but he had overlooked the crushing effect of atmospheric pressure upon them.

Three months after the ascent of their first uncrewed balloon in 1783, the Montgolfier brothers repeated the experiment in the presence of the French King and his court, sending up a sheep, a cock, and a duck. These animals thus became the first living things to be carried in an airborne vehicle. On 15 October of the same year, du Rozier, another Frenchman, made the first captive ascent by man (he was attached by a rope to the ground) and on 21 November he made the first free flight, covering nearly five and a half miles in about 25 minutes.

The Montgolfier brothers described their balloon in scientific journals, but oddly enough omitted to state what it was filled with. Their account was read by two brothers named Robert who engaged the physicist, Jacques Charles, to make them a similar balloon. Charles assumed that the Montgolfiers had used hydrogen, and inflated his balloon with this gas; it was the first time hydrogen had been used for such a purpose. The balloon soared to 3,000 feet, fell into a field 15 miles away, and so terrified the French peasants that they destroyed it. When Charles finally saw the Montgolfier balloon he was astonished to learn that hot air had been its only lifting power. Ten days later Charles ascended in a hydrogen-filled balloon, and to Charles is due the credit for putting a valve at the top and for attaching a carrier to the hoop and netting.

Vincent Lunardi, secretary to the Neapolitan ambassador, made ballooning popular in Great Britain. He was to have taken an Englishman with him as a passenger when he made an ascent on 15 September 1784 at an occasion graced by the Prince of Wales. But the impatient crowd could not wait for the balloon to be properly filled, and Lunardi therefore substituted for his passenger a pigeon, a dog, and a cat. He also had oars with which to row himself through the air at different levels. The pigeon escaped, the cat was badly affected by the cold, one of the oars broke, and when Lunardi descended he had difficulty in persuading anyone to seize the ropes in order to secure the balloon.

On 7 January 1785 Jean-Pierre Blanchard with Dr Jefferies, and American, crossed the English Channel from Dover to the Forest of Guines in a balloon fitted with a parachute and wings, after having had to jettison practically everything removable in order to maintain height, including most of their clothing. One of the main difficulties was that there was no means of controlling the balloon against strong winds, and that it was only just possible to control the take-off and landing.

Rozier and a companion in a fire balloon emulated their feat in the opposite direction from Boulogne, but the envelope caught fire and both men were killed.

The first successful flight by an Englishman, James Sadler, had taken place in October of the previous year when he was airborne for half an hour.

In October 1812 Sadler attempted to cross the Irish Sea, but, after drifting at a great height over the Isle of Anglesey, he came down in the sea and was fortunate enough to be rescued.

The most celebrated early English aeronaut was Charles Green who, in 1836, with Robert Holland, M.P., and another companion named Mason, covered 480 miles non-stop in a journey from London to Weilburg, a record unbeaten until 1907. It was Green who invented the guide rope which trails below the gondola. When it drags on the ground the balloon is relieved of weight and tends to rise, and, naturally, when the balloon sustains the rope's full weight, it tends to sink.

Later developments

When the balloon was still in its infancy its use as a weapon of war was already recognized. The French army established a school for aerostiers at Meudon. With one of their balloons they demoralised Austrian troops who promptly lifted the siege of Maubeuge. And in 1849 the Austrians used pilotless hot-air balloons equipped with timing devices to bomb Venice – the first recorded air-raid.

But until the Siege of Paris by the Prussians in 1870–1871 the balloon was not regarded very seriously. However, its importance was no longer in doubt after 66 free balloons had left the beleaguered city carrying refugees and carrier-pigeons across the enemy lines. Later, the pigeons returned to Paris with micro-filmed letters from the outside world.

The Balloon School of the Royal Engineers was formed at Chatham in 1878, and continued until it was superseded in 1911 by the Air Battalion, Royal Engineers, which was established to create a body of expert airmen. The year 1912 saw the creation of the Royal Flying Corps, which ceased to exist in turn in 1 April 1918, when it was absorbed into the newly established Royal Air Force who maintained a school of balloon training at Larkhill, Salisbury Plain, for many years after the end of World War 1.

Like all Man's inventions for the conquest of a new element, the balloon had its tragedies. One was the daring attempt of the Swedish explorer, Andree, with two companions, to float across the North Pole. They left Danes Island, Spitsbergen, on 11 July 1897, and were never seen again, but by a curious chance, the remains of their expedition were discovered in 1930 under the ice of White Island, Spitsbergen.

Early on, the balloon was used for scientific purposes. Then, for the first half of the 19th century, few such flights seem to have been made until the committee of Kew Observatory employed the famous Green, a great aeronaut, and Welsh, a member of their staff, acted as an observer on the flights. Since then, a wealth of scientific data has been obtained. In particular, balloons are used for meteorological research, and also for several kinds of scientific research where it is important to prevent interference from the atmosphere.

Among the important later flights are stratosphere ascents of August Piccard in 1931 and1932 in an air-tight gondola. His twin brother, Jean Felix, assisted him in his research work in organic chemistry. In 1957, Major D. Simons, of the American Air Force, attained a height of 100,000 feet, a record for an ascent by manned balloon.

All modern aviators must owe a debt to the Frenchman Garnerin, who made the first public parachute jump from a height of over 2,000 feet in 1797.