ion propulsion

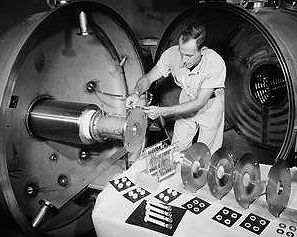

A NASA engineer prepares an early ion engine for a vacuum chamber test in 1959. Lined up at right are the major electrical parts.

Ion propulsion is a form of electric space propulsion in which ions are accelerated by an electrostatic field to produce a high-speed (typically about 30 kilometers per second) exhaust. An ion engine has a high specific impulse (making it very fuel-efficient) but a very low thrust. Therefore, it is useless in the atmosphere or as a launch vehicle, but extremely useful in space where a small amount of thrust over a long period can result in a big difference in velocity. This makes an ion engine particularly useful for two applications: (1) as a final thruster to nudge a satellite into a higher orbit and or for orbital maneuvering or station-keeping, and (2) as a means of propelling deep-space probes by thrusting over a period of months to provide a high final velocity. The source of electrical energy for an ion engine can be either solar (see solar-electric propulsion) or nuclear (see nuclear-electric propulsion).

Two types of ion propulsion have been investigated in depth over the past few decades: electron bombardment thrusters and contact ion thrusters. Of these, the latter remains in the research stage while the former has already been used on a number of spacecraft. Specifically, the variety of electron bombardment thruster known as XIPS (a Hughes/Boeing product) is used for station-keeping by some geosynchronous satellites, while the NSTAR ion engine (developed by NASA and Hughes) propelled the Deep Space 1 interplanetary probe.

One of the most promising new developments in ion propulsion is the DS4G (dual-stage 4-grid) ion engine, developed by the European Space Agency and a group at the Australian National University. This was first tested by ESA in 2005. The DS4G thruster achieves much higher voltages to be used than previously thought possible, resulting in a more powerful post acceleration of the extracted ions. The thruster was tested in a large space simulation chamber in the ESA Technology centre in the Netherlands at a remarkable 30,000 volts and produced an ion exhaust plume that travelled at 210 kilometers per second – over four times faster than state-of-the-art ion engine designs achieve.

History of ion propulsion

Among the most difficult challenges in the early development of ion engines was proving that injecting electrons could neutralize an ion beam. Continually spewing positively charged ions will leave a spacecraft with a negative charge so great that the ions are attracted back to the spacecraft. The solution is an electron gun that dumps the electrons into the ion stream, thus neutralizing both spacecraft and exhaust. But the beam's interaction with the walls of even a large vacuum chamber makes it very difficult to conduct meaningful beam neutralization experiments on Earth. These uncertainties led to considerations for flight testing electric engines. Another challenge of electronic propulsion involved developing an efficient technique to produce ions. Working at NASA's Lewis, Harold Kaufman invented an electron-bombardment technique to ionize mercury atoms. At NASA/Marshall, a process was under development whereby cesium atoms would become ionized upon contact with a hot tungsten or rhenium surface. Marshall's major development in electrical propulsion centered, however, on a 30-kilowatt ion engine development contract, initiated in Sep 1960 with Hughes Research Laboratory in Malibu, California. At first, Marshall directed Hughes to design a laboratory model of an ion engine. The 0.01 pound-thrust model would be followed by the development of a 0.1 lb-thrust engine. Marshall later modified the Hughes contract to include a flight test model ion engine, primarily to determine whether a beam neutralization problem existed in space.

On 1 August 1961, NASA awarded a contract to the Astro-Electronics Division of RCA to design and build a payload capsule for flight-testing electric propulsion engines. The program called for seven capsules, three for ground tests and four for actual flight tests. Each capsule was expected to carry two electric engines. The first was expected to carry one cesium-fueled ion-engine representing Stuhlinger's design with the Hughes engine. The second was expected to carry one mercury-fueled ion engine representing Kaufman's design with the Lewis engine. Plans called for the engines to operate from 1 to 2 kilowatts of power. Hughes demonstrated an ion engine on 27 September 1961, at its research laboratories in Malibu. Stuhlinger was among those on hand to greet the scientific and technical writers who attended the event.

Ion propulsion in science fiction

Frequent mention of ion propulsion has been made in works of science fiction for several decades. It was featured, for example, in a September 1968 episode of Star Trek called "Spock's Brain," in which invaders steal Spock's brain and flee in an ion-powered spacecraft.