teeth

Figure 1. Mouth and jaws of an adult human showing the position of the teeth. Top left: structure of a molar tooth.

Figure 2. The 32 adult human teeth.

Figure 3. Diagrammatic section of a tooth.

Figure 4. The face of a six-year-old child showing the milk teeth in position and the developing permanent teeth (in red).

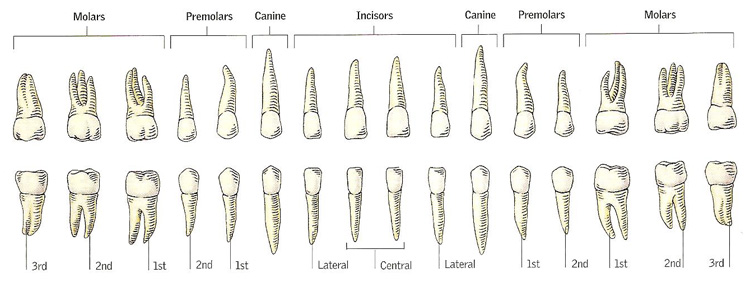

Figure 5. Milk teeth

Fig 6. Permanent teeth

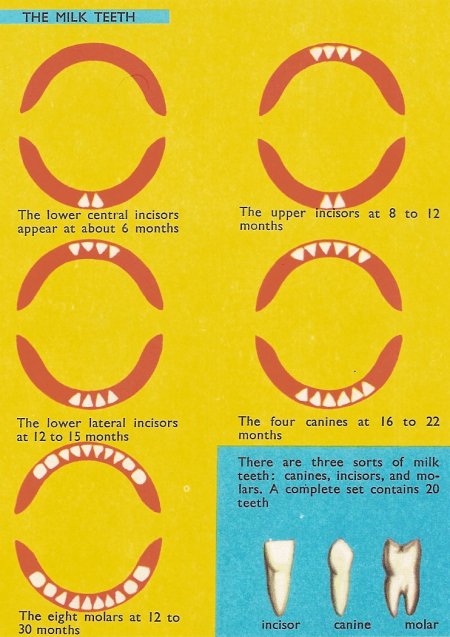

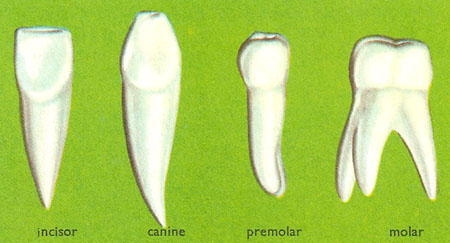

Figure 7. Types of adult teeth.

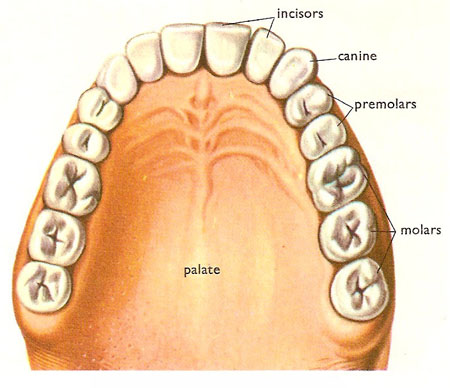

Figure 8. A view of teeth in the upper jaw.

Figure 9. Crocodile teeth.

Teeth are hard bonelike structures in the jaws of humans and other vertebrates which are used for biting and chewing or for attack and defense.

An adult human normally has 32 teeth – 16 in each jaw. The upper jaw has on each side two incisors, one canine, two premolars and, at the back, three molars. The same is true of the lower jaw.

Dental formula

The number of teeth in an animal can be expressed conveniently by using the dental formula. This gives the number of teeth of each type in one half of each jaw reading from the front (incisors) to back (molars). Thus the dental formula for humans is 2123/2123. For a rabbit, which has no canine teeth at all in its jaws the formula is 2033/1023. The primitive placental condition (i.e., that found in the early placental mammals) is 3143/3143 but few animals retain the full set of 44.

Arrangement and function of teeth

The tooth arrangement depends to a large extent upon the feeding method and the nature of the food. Humans are omnivorous (eating all types of food) and consequently our teeth are not highly specialized when compared with the grinding teeth of herbivores and the cutting teeth of carnivores. Incisors are retained in most mammalian groups as chisel-shaped biting or cutting teeth. The canine is highly developed in hunting carnivores as a stabbing and tearing tooth. In humans it is rather reduced and functions almost as another incisor. Many herbivorous animals have lost the canine tooth altogether. The premolars and molars of humans are the grinding and chewing teeth. The surface of these teeth is covered with triangular or conical ridges (cusps) which fit into hollows of the opposing teeth when the jaws are brought together. Chewing movements then cause the teeth to act as millstones and grind up the food.

Structure of teeth

Although our teeth are modified for various purposes, they are all constructed to a definite pattern. Projecting from the gum is the crown of the tooth. The part embedded in the gum and reaching into a socket in the jawbone is known as the root. The body of the tooth is made up of a hard, pale yellowish, bonelike substance called dentine. Inside this is a cavity – the pulp cavity – which contains blood vessels and nerves. Branches from these, together with fine cytoplasmic threads, penetrate the maze of fine canals which spread throughout the dentine. When the latter is damaged, by decay or in some other way, the nerve endings are stimulated and we feel pain.

Covering the crown of the tooth is layer of enamel of varying thickness. It is made up almost entirely of apatite crystals with calcium phosphate filling. Apatite crystals are composed of calcium phosphate plus calcium fluoride or calcium chloride. Calcium phosphate is also mainly responsible for the hardness of dentine. The enamel layer crystals are elongated and are all arranged with their ends toward the surface of the enamel.

Around the root of the tooth, enamel is replaced by cementum (the cement), another bonelike material which fixes the tooth firmly in the socket of the jaw. However, between the bone of the jaw and the cementum layer there is a layer of tissue, called the periodontal membrane, which is in contact with the tissues of the gums and with the pulp cavity. Incisor and canine teeth have a single root, premolars have a double root, and molars have three branches to the root.

Deciduous (milk) teeth

Whereas an adult human has 32 teeth, a child up to about the age of six has only 20 teeth. These are the milk teeth or deciduous teeth which are gradually replaced by the permanent teeth after the age of about six years. There are no molars in the milk set but the teeth corresponding to the premolars are known as the milk-molars and perform the same grinding function.

The first milk teeth to erupt (break through the gums) are usually the two central incisors in the lower jaw. These normally appear between eight and ten months after birth. Then, in a fairly regular order which takes 18 months to 2 years, a further 18 teeth push their way through the gums. By the time a child is 2 or 2½ years old it should have a full set of 20 teeth. Although quite small, the deciduous teeth are very strong and well able to deal with the hardest foods that the child may come across.

The teeth are formed with the substance of the jawbones; the maxilla above and the mandible below. As they erupt they have to push their way through the tissues which cover the bones and in this process can cause marked inflammation. In a baby this is enough to cause a temperature and considerable disturbance of appetite and well-being.

Teething

Teething is the period when a baby cuts his or her primary teeth. Usually, the first signs of teething occur at about six months of age.

While teething, a baby may be irritable, fretful, clingy, may have difficulty sleeping, and may cry more than usual. Extra saliva may be produced, resulting in dribbling, and the baby tends to chew on anything that comes to hand. Before a tooth emerges, the gum may become red and swollen. When molars erupt, the cheek may feel warm and look red on the affected side of the mouth.

Treatment

Symptoms may be relieved by the use of painkilling gels that are rubbed on the swollen gums, or liquid preparations.

Permanent teeth

The first permanent teeth appear at the age of about six years. These are the first molars, sometimes called the "six-year molars." They are the first permanent teeth to erupt. Thereafter, during the course of 5 or 6 years, the milk teeth are all pushed out by permanent teeth which grow up beneath them. Incisors are replaced first, then premolars and then canines, the latter appearing as permanent teeth at eleven years or so. When all the milk teeth have been lost the 4 second molars appear immediately behind the first molars, at about 12 years. Only the third molars are now needed to make a complete set of permanent teeth.

These four teeth, often called wisdom teeth, seldom appear before the 15th year. In some people they may not erupt until much later in life; in others, their eruption may be impeded by the second molars. This condition is known as an impacted wisdom tooth, and because it is a painful condition it frequently requires the removal of the tooth.

Origin and development of teeth

Although teeth are composed of a hard bone-like tissue, they are in fact derived from various skin tissues in much the same way as the placoid scales (denticles) of the dogfish and its relatives (the Elasmobranch fish). It is fairly certain that the placoid scale and the teeth have a common origin in the bony plates that covered the bodies of primitive fish. The placoid scales, like teeth, have a pulp cavity surrounded by dentine and enamel, and, in only slightly modified form, function as teeth in the mouths of elasmobranchs.

More concrete evidence of the origin of teeth is obtained by studying their development in the gum. Human teeth are formed in the following way. In the early embryo the skin along the future line of the jaw-bones thickens and is known as the dental lamina. The edge of this extends into the tissues of the jaw and forms bud-like thickenings at intervals along the jaw. There are, at first, ten of these thickenings in each jaw. They are the "buds" of the first set of teeth.

The dental lamina later extends beyond the last deciduous tooth bud and slowly forms the buds of the permanent molars. When the embryo is about three months old the dental lamina forms further tooth buds on the inside of the developing milk teeth. These are the buds of the permanent teeth. They develop in the same way as the milk teeth but much more slowly.

The epithelial tissues of the tooth buds grow inward and form a bell-shaped structure in which a group of cells shows up densely and is termed the enamel knot. Under this knot, cells of the connective tissue become dense, forming the beginnings of the tooth body, the tooth papilla.

The cells of the papilla grow and multiply and push up under the enamel knot, forming a simple tooth-shaped structure. The cells of the enamel knot get larger and begin to produce enamel while some cells of the papilla start to release dentine. For the laying down of good hard material and its impregnation with calcium and other minerals, salts and vitamins – especially vitamin D – are needed in the blood. The hard layers are first deposited at about 20 weeks old by which time the bone of the jaws has started to form as a cup surrounding the developing teeth. More enamel and dentine are produced until the crown of the tooth is complete. The time required depends on upon the type of tooth but when the crown is complete the tooth erupts (i.e., breaks through the gum surface) by growth of the root. The latter continues to grow for a while until it is completely enveloped in the jawbone which has grown up around it. Cement is produced by the tissues of the papilla when the root begins to grow. When the root is fully formed the opening of the pulp cavity closes so that very little nutrient transfer can occur. Growth then ceases although the tissues still receive enough nourishment to stay alive.

The permanent teeth continue to develop slowly under the milk teeth. When the crown of the permanent tooth is fully formed, its root begins to grow. This causes an increase in pressure on the base of the milk tooth. The result is that the periodontal membrane and the cement and even part of the milk tooth root are broken down by enzymes and by special scavenging cells, called macrophages, which absorb the material in the manner of a feeding amoeba. When the cement and the membrane have gone there is no firm attachment of the tooth to the jaw – the tooth in fact becomes loose and eventually falls out, leaving a clear path for the permanent tooth which now rapidly grows up through the gum to take its place in the adult tooth row. When it has reached full size and is firmly embedded in its socket, the tooth ceases to grow because the opening of the pulp cavity closes just as in the milk teeth.

The gum is a mass of dense, fibrous tissue attached to the jaw bones. It is continuous with the periodontal membrane of the tooth socket which it supplies with food and oxygen via its rich blood supply.

Dental caries

Decay and crumbling of the substance of a tooth, known as dental caries, is caused by the metabolism of bacteria in plaque attached to the surface of the tooth. Acid formed by bacterial breakdown of sugar in the diet causes demineralization of the enamel of the tooth. Without preventative measures or treatment, caries spreads into the dentine and progressively destroys the tooth. It is the most cause of toothache, and once infection has spread to the pulp it may extend through the root canal into the periapical tissues to cause an apical abscess. Fluoride in small quantities protects against caries.

Caries, in general, is the decay or softening of hard tissues, and, as well as teeth, may affect for bone, as in the case of spinal tuberculosis.

Other terms used in dentistry

abutment

A component of a dental bridge (see below) or implant.

acid-etch technique

A technique for bonding resin-based materials to the enamel of teeth; it is used to retain and seal the margins of fillings, to retain brackets of fixed orthodontic appliances, and to retain resin-based fissure sealants and adhesive bridges. A porous surface is created by applying phosphoric acid for one minute or less.

anodontia

An absence of teeth because they have failed to develop. It is more common for only a few teeth to develop.

aerodontalgia

A pain in the teeth due to change in atmospheric pressure during air travel or the ascent of a mountain.

apexification

A procedure to allow the end of the root of an immature tooth to form a hard tissue barrier following traumatic injury that has caused the pulp to die.

apexogenesis

A procedure to allows the root tip to continue forming when an immature tooth has sustained limited injury following trauma.

apical abscess

An abscess in the bone around the apex of a tooth. An acute abscess is extremely painful, causing swelling of the jaw and sometimes also the face. A chronic abscess may cause no pain or swelling. An abscess invariably results from damage to and infection of the pulp of the tooth. Treatment is drainage and root canal treatment or extraction of the tooth; antibiotics may give temporary relief.

apicectomy

Surgical removal of the apex of the root of a tooth, now often referred to as root end resection. It is usually accompanied by placement of a filling in a cavity prepared in the root end. It is carried out when root canal treatment has failed and cannot be redone.

articulator

An apparatus for relating the upper and lower model's of a patient's dentition in a fixed position, usually with maximum tooth contact. Some articulators can reproduce jaw movements. They are used in the construction of crowns, bridges, and dentures.

attrition

The wearing of tooth surfaces by the action of opposing teeth. A small amount of attrition occurs with age but accelerated wear may occur in bruxism and with certain diets.

bite-wing

A dental X-ray film that provides a view of the crowns of the teeth in part of both upper and lower jaws. This view is used in the diagnosis of caries and periodontal disease.

bridge

A partial denture held in place by anchorage to adjacent teeth, which may be natural or implants. Depending on the situation a bridge may be permanently installed or removable; anchorages are of various kinds. Usually, only one or a few teeth in a series are artificially replaced in this manner. The supporting teeth (or implants) are known as abutments, and the artificial teeth that fit over them are called retainers. The replacements of missing teeth are known as pontics.

bur

A cutting instrument used in dentistry that fits in a dental handpiece. It may be made from hardened steel, stainless steel, or tungsten carbide, or be coated with diamond particles. Burs are mainly used for cutting cavities in teeth, removing old restoration, and preparing teeth to receive artificial crowns.

canine

The third tooth from the midline of each jaw. There are thus four canines, two in each jaw, in both the permanent and primary (deciduous) dentitions. I(t is known colloquially as the eye tooth.

cavity

The hole in a tooth caused by caries or abrasion. Also, the hole shaped in a tooth by a dentist to retain a filling.

cavity varnish

A solution of natural or synthetic resin in an organic solvent. It is used as a sealer for amalgam fillings or as a coating over newly inserted cement fillings.

cement

Any of a group of materials used in dentistry either as fillings or as lutes for crowns. Glass ionomer cements are used for filling, and zinc phosphate, zinc polycarboxylate, and glass ionomer cements are used for luting. Zinc oxide-eugenol cements are widely used as temporary fillings or as an impression material.

cementum

A thin layer of hard tissue on the surface of the root of a tooth. It attaches the fibers of the periodontal membrane to the tooth.

clasp

The part of a denture or orthodontic appliance that keeps it in place. It is made of flexible metal.

crossbite

A condition in which some or all of the lower teeth close outside the upper teeth during normal closure.

crown

(1) The part of a tooth normally visible in the mouth and usually covered by enamel. (2) A dental restoration that covers most or all of the natural crown. It may be made of porcelain (sometimes bonded to a metal substructure), gold, or a combination of these, or less commonly other materials. Most crowns are like thimbles and are custom made to fit over a trimmed-down tooth. Preformed metal crowns may be used on primary teeth. A post crown is used to restore a tooth when insufficient of the natural crown remains. A post is inserted into the root and the missing center of the tooth is built up; over it is fitted a thimble-like crown to restore the natural shape of the tooth. Root canal treatment is required before a post crown can be made. The only real option for a broken down tooth before crowns was tooth extraction. Crowns have given dentists, and in turn patients, the ability to fix certain dental situations.

cusp

Any of the cone-shaped prominences on teeth, especially the molars and premolars.

dental nerve

The dental nerve is either of two nerves that supply the teeth; they are branches of the trigeminal nerve. The inferior dental nerve supplies the lower teeth and for most of its length consists of a single large bundle; thus anesthesia of it has a widespread effect. The superior dental nerve, which supplies the upper teeth, breaks into separate branches at some distance from the teeth and it is possible to anesthetize these individually with less widespread effect for the patient.

dentinogenesis

The formation of dentine by odontoblasts. Although dentinogenesis continues throughout life, very little dentine is formed later than a few years after tooth eruption unless it is stimulated by caries, abrasion, or trauma.

dentition

Dentition is the type, number, and arrangement of teeth in an animal. An adult human has 32 teeth. The incisors are used for cutting; the canines for gripping and tearing; and the molars and premolars for crushing and grinding food. A herbivore has relatively unspecialized teeth that grow throughout life to compensate for wear (plant fibers are very tough) and are adapted for grinding. A carnivore has a range of specialized teeth related to killing, gripping, and crushing bones. In carnivores, unspecialized milk teeth are replaced by more specialized adult teeth, which have to last a lifetime.

denture

A removable replacement for one or more teeth on some type of plate or frame. A complete denture replaces all the teeth in one jaw, and is usually made entirely of acrylic resin. A partial denture replaces some teeth because others still remain. It is designed to restore function with the least potential damage to the remaining teeth. The framework of the denture is often made of metal because of its strength.

diastema

A space between two teeth.

drill

A rotary instrument used to remove tooth substance, particularly in the treatment of caries. It consists of a dental handpiece that takes variously shaped burs. Most drilling is done with an air-driven turbine handpiece, but some is performed with a much slower mechanically driven handpiece. Handpieces usually have a waterspray coolant and may have a fiber-optic light.

embrasure

The space formed between adjacent teeth.

endodontics

The study, treatment, and prevention of diseases of the pulp of teeth and their sequelae. A major part of treatment is root canal treatment.

extrusion

(1) The forced eruption of a tooth either by means of an orthodontic appliance or surgically; for example, to realign a tooth that has failed to erupt or has been accidentally forced into the jaw. (2) The partial displacement of a tooth from its socket as a result of traumatic injury.

face-bow

An instrument for transferring the jaw relationship of a patient to an articulator to allow reproduction of the lateral and protrusive movements of the lower jaw.

fissure sealant

A material that is bonded to the enamel surface of teeth to seal the fissures, in order to prevent dental caries. Composite resins, unfilled resins, and glass isomer cements have been used as fissure sealants.

hypodontia

Congenital absence of some of the teeth.

incisor

Any of the four front teeth in each jaw, two on each side of the midline.

inferior dental block

A type of injection to anesthetize the inferior dental nerve. Inferior dental block is routinely performed to allow dental procedures to be carried out on the lower teeth on one side of the mouth.

inferior dental canal

A bony canal in the mandible on each side. It carries the inferior dental nerve and vessels and for part of its length its outline is visible on a radiograph.

lute

A thin layer of cement inserted into the minute space between a prepared tooth and a crown or inlay to hold and seal it permanently in place.

malocclusion

A condition in which there is an abnormal arrangement of the teeth or discrepancy in the relationship of the jaws. It is usually treated by orthodontics.

mesial

Designating the surface of a tooth toward the midline of the jaw.

mesiodens

An extra tooth that may occur in the midline of the palate, between the central incisors, and may interfere with their eruption.

milk teeth

Colloquial name for the primary teeth of children.

molar

In the permanent dentition, the sixth, seventh, or eight tooth from the midline on each side in each jaw. Permanent molars do not replace primary teeth. In the primary dentition, molars are the fourth and fifth teeth from the midline on each side in each jaw.

molar-incisor hypomineralization

A deficiency in the mineralization of permanent first molar and incisor teeth, though to be due to a disturbance of development around the time of birth.

occlusal

Denoting or relating to the biting surface of a premolar or molar tooth. Occlusion is the relation of the upper and lower teeth when they are in contact. Maximum contact between the teeth is known as intercuspal or centric occlusion.

odontoblast

A cell that forms dentine. Odontoblasts line the pulp and have small processes that extend into the dentine.

oligodontia

The congenital absence of some of the teeth.

orthodontic appliance

An appliance used to move teeth as part of orthodontic treatment. A fixed appliance is fitted to the teeth by stainless steel bands or brackets that hold a special archwire, to perform complex tooth movements. A removable appliance is a dental plate with appropriate retainers and springs to perform simple tooth movements; it is removed from the mouth for cleaning by the patient.

orthodontics

The branch of dentistry concerned with the growth and development of the face and jaws and the treatment of irregularities of the teeth.

overjet

The horizontal overlap of the upper incisor teeth in front of the lower ones.

peridontal

Denoting or relating to the tissues surrounding the teeth. The peridontal ligament or membrane is the ligament around a tooth, by which it is attached to the bone.

periodontal disease

A disease of the tissues that support and attach the teeth – the gums, periodontal ligaments (or membrane), and alveolar bone. It is caused by the metabolism of bacterial plaque on the surfaces of the teeth adjacent to these tissues. Periodontal disease includes gingivitis and the more advanced stage of periodontitis, which results in the formation of spaces between the gums and the teeth, the loss of some of the fibers that attach the tooth to the jaw, and the loss of bone. The disease is widespread and is the most common cause of tooth loss in older people.

periodontium

The tissues that support and attach the teeth to the jaw: the gums, periodontal ligaments (or membrane), and cementum.

periodontology

The branch of dentistry concerned with the tissues that support and attach the teeth and the prevention and treatment of periodontal disease.

plaque

A layer that forms on the surface of a tooth, principally at its neck, composed of bacteria in an organic matrix. Under certain conditions the plaque may cause gingivitis, periodontal disease, or dental cares. The purpose of oral hygiene is to remove plaque.

premolar

Either of the two teeth on each side of each jaw behind the canines and in front of the molars in the adult dentition.

preventative dentistry

The branch of dentistry concerned with the prevention of dental disease. It includes dietary counseling, advice on oral hygiene, and the application of fluoride and fissure sealants to the teeth.

preventative resin restoration

A hybrid between a fissure sealant and a conventional filling that is used to treat early dental caries involving dentine.

prilocaine

A local anesthetic used particularly in dentistry. It is administered by injection.

primary teeth

The first set of teeth, which develop in infancy. These teeth are normally shed just before the eruption of their permanent successors. In the absence of permanent successors they can remain functional for many years.

protrusion

(1) Forward movement of the lower jaw. (2) A malocclusion in which some of the teeth are further forward than usual.

pulp

The mass of tissue in the pulp cavity, at the center of a tooth. It is surrounded by dentine except where it communicates with the rest of the body at the apex. The pulp within the crown portion of the pulp cavity is described as coronal pulp; that within the root canal is the radicular pulp. Pulpitis is inflammation of the pulp: a frequent cause of toothache.

pulp capping

The procedure of covering an exposed tooth pulp following trauma with a medicament (usually based on calcium hydroxide), which is then covered with a temporary or permanent restoration. In pulpotomy, part of the pulp is cut back and then covered.

retainer

(1) A component of a partial denture that keeps it in place. (2) An orthodontic appliance that holds the teeth in position at the end of active treatment. (3) A component of a bridge that is fixed to a natural tooth.

retrusion

(1) Backward movement of the jaw. (2) A malocclusion in which some of the teeth are further back than usual.

root

The part of a tooth that is not covered by enamel and is normally attached to the alveolar bone by periodontal fibers.

root canal treatment

The procedure of removing the remnants of the pulp of a tooth, cleaning, and shaping the canal inside the tooth, and filling the root canal. The entire treatment usually extends over several visits. It is used to treat toothache and apical abscesses.

rubber dam

A sheet of rubber used to isolate one or more teeth during treatment.

scaler

An instrument for removing calculus from the teeth. It may be a hand instrument (usually sickle or curette) or one energized by rapid ultrasonic vibrations.

veneer

A facing of composite resin or porcelain applied to the surface of a tooth to give improve shape and/or color. The tooth requires minimal preparation and the facing is retained by enamel that has been treated by the acid-etch technique. Veneers are a more conservative way of treating discolored teeth than by crowns.

wisdom tooth

The third molar on each side of either jaw, which erupts normally around the age of 20 years.

Teeth in other animals

Only in the mammals do we find the various types of teeth described above. In all lower vertebrates the teeth are simple conical structures, usually without roots, and are present in greater numbers than in mammals as a rule. They are attached to the jaws by cement or by fibrous tissue (ligaments) but apart from crocodile and some fish teeth, they are not placed in sockets. Frequently, especially in fish, teeth are found in the roof and base of the mouth as well as in the jaws. Although the size of teeth may vary in an individual animal – the crocodiles have both large and small teeth – all are of the same general shape. Some modifications are found in fish that feed off molluscs. The teeth are often flattened and may be joined together in plates in order to crush the shells. The poison fangs of snakes are modified teeth. They are elongated and grooved to carry the venom from the poison glands into the wound made by the teeth. In contrast with mammals, where there are usually the two sets of teeth described for humans, reptiles and most other lower vertebrates replace their teeth many times, new ones replacing worn ones regularly throughout life.

Modern birds are without teeth although fossils show that the earliest birds had simple conical teeth similar to those of their reptilian ancestors.

All mammalian teeth can be classed by the four types described earlier but, as we have seen, they may be modified according to the feeding habits and diet of the animals concerned. The molars of cows and other grass or foliage-feeding animals are very large and have a complex pattern of ridges and grooves to ensure adequate grinding of the food. Teeth such as these, which are subject to hard wear, continue to grow throughout life as the root canal remains open. The dog and related carnivores have very sharp, pointed carnassial teeth. These are formed by the last pair of premolars in the upper jaw and the first molar of the lower jaw. The chewing motion of the jaws causes the teeth to shear through meat. Other tooth modifications include the tusks of elephants, which are greatly enlarged upper incisors. Whalebone whales and some ant-eating mammals have no teeth at al.