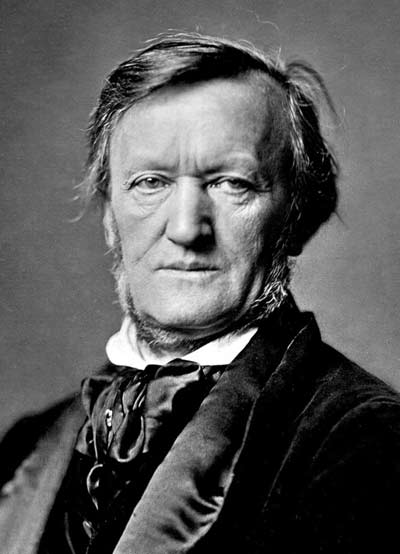

Wagner, Richard (1813–1883)

Wagner in 1871.

A domestic vision of Wagner at home with his second wife Cosima, daughterof Franze Liszt.

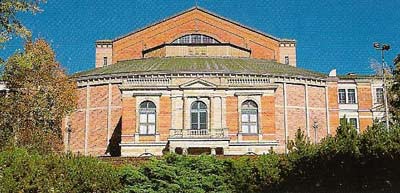

The Festspielhaus at Bayreuth, built to Wagner's specifications by Gottfried Semper between 1871 and 1876 for te performance of Wagnerian music dramas.

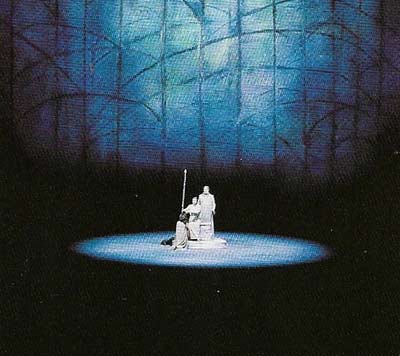

The "Good Friday" scene from a 1950s Bayreuth production of Parsifal, produced by Wagner's grandson Wieland.

The figure of Richard Wagner straddles the 19th century like a colossus. Composer, critic, polemicist, his abundant energy allowed him to a pursue a vision with a ruthless single-mindedness beyond the comprehension of ordinary mortals.

His operas, rooted in the German Romantic tradition, remain (like Verdi's) the cornerstones of the modern repertoire, but they require performers of extraordinary power and stamina. There are still few sopranos and tenors able to do justice to roles such as Siegfried, Briinnhilde, Tristan, and Isolde, and many singers have burnt out their voices in the attempt.

Early years

Friedrich Wagner died of typhus soon after his son Richard was born, and his mother Johanna married Ludwig Meyer, who introduced his stepson to the world of the theater and music. The family moved to Dresden, where the young Wagner came into contact with Weber, then conductor at the Royal Theatre. According to Wagner, it was Weber who instilled in him "a passion for music". After his stepfather's death the family returned to Wagner's birthplace, Leipzig, where he completed his education at school and university. By now he was passionately interested in the theater, and in 1832 he began work on his first, abortive, opera. He realized from the start that he would only ever be able to work with his own librettos.

He began his theatrical career as a chorus-master in Würzburg, where he completed his first opera Die Feen (The Fairies). It remained unperformed, but already Wagner was showing a dogged determination to succeed. He began work on a third opera, Das Liebesverbot (The Ban on Love), based on Shakespeare's Measure for Measure, and joined a traveling theater company as music director. Das Liebeserbot had a single performance in Magdeburg in 1836, before the company went bankrupt. By this time Wagner had fallen in love with the actress Minna Planer, whom he married on 24 November. Six months later Minna ran off with another man, but was reconciled with her husband in October 1837. Their relationship remained stormy.

Paris

Wagner was working at Riga (now in Latvia) when he began Rienzi. By March 1839, when his contract ended, he was heavily in debt (a leitmotif of his career). He, Minna, and their huge dog were obliged to flee from his creditors by ship to London.

In September they arrived in Paris, where Wagner hoped to establish himself as a composer. Instead he found himself trying to make ends meet from journalism, while financial problems landed him in a debtors' prison. He did, however, come into contact with a great deal of new music, and with literature, especially the Germanic legends of Tannhäuser and Lohengrin. His Paris period then laid the foundations of several future operas, including Der fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman), which he finished in 1841. The famous, storm-tossed overture to this dramatic tale, of a restless ghost who is finally redeemed by faithful love, was inspired by Wagner's own experiences on the ship from Riga.

Dresden

Is 1842 Rienzi was finally performed, with considerable success, at the Dresden court theater, which agreed to mount The Flying Dutchman in January 1843. Although Wagner was disappointed with the latter's reception, his career was finally launched, and he was offered the post of conductor in Dresden. In April 1843 he completed Tannhäuser, based on the legend of the knight seduced from his duties by the pleasures of Venus who is redeemed by a divine miracle. Tannhäuser was premiered in Dresden in October 1845.

Wagner began work on Lohengrin, which was finished in 1848, the year of revolution in Europe. Wagner's pro-revolutionary sympathies implicated him (by default) in the Dresden uprising of May 1849, and in fear of his life he escaped to Switzerland. He settled in Zurich, where he worked on his creative manifesto, Opera and Drama, and also began work on the texts of a new project, based on the ancient Nordic saga of the Nibelungs. Lohengrin could not now be produced in Dresden, so Wagner sent the score to Liszt, who had sufficient confidence in it to risk censure by mounting a production in Weimar in August 1850. It eventually became an outstanding success, although Wagner himself was unable to attend a performance until 1861.

Music of the future

Lohengrin— another legendary tale of knightly chivalry with a strong magical element – marked the end of Wagner's involvement with conventional German Romantic opera. In Opera and Drama he set out his visionary ideal of the "music of the future", in which music and drama became indivisible. The last 30 years of his life were dedicated to realizing this ideal.

By 1852 Wagner was again chronically in debt. He was helped by the merchant Otto Wesendonk, with whose wife, Mathilde, he fell in love. Their affair inspired the opera Tristan and Isolde, which Wagner began in 1857. This passionate portrayal of an adulterous love which can find fulfilment only in death is one of the supreme achievements of Western art. In it, Wagner pushed chromatic harmony to its limits, from the unresolved, "yearning" motif of the Prelude to the ecstatic dignity of Isolde's "Liebestod" ("love-death") in which she is finally united with Tristan as the strained "Tristan chord" achieves its radiant resolution.

Munich

Wagner's personal troubles continued. His wife discovered his liaison with Mathilde Wesendonk, and Wagner fled to Venice. With the police at his heels he moved on to Lucerne (where he finished Tristan) and then to Paris, where performances of Tannhäuser in 1861 were disrupted by an organized and noisy claque.

A political amnesty of 1860 allowed Wagner to return to Germany, but he spent the next three years traveling from city to city dodging his creditors, until a knight in shining armour appeared in the person of the "mad" King Ludwig II of Bavaria. Ludwig paid off Wagner's debts and offered him sanctuary in Munich, where Tristan end Isolde was first performed on 10 June 1865, under the baton of Hans von Bülow. Wagner repaid Bülow by beginning an affair with his with Cosima (daughter of Liszt and the Countess Marie d'Agoult), who bore him two daughters, Isolde and Eva. Wagner now had to leave Germany again in the face of Bavarian opposition to his powerful influence over the king and the vast sums of money that were being lavished on him from the public purse. Minna Wagner having died in 1866, Cosima von Bülow moved in with Wagner at his new home – financed by Ludwig – at Tribschen, outside Lucerne, where their son Siegfried was born in 1869. (This event inspired Wagner to compose the Siegfried Idyll, rehearsed in secret and played as a surprise for Cosima on Christmas morning.) After Cosima's divorce from Bülow, she and Wagner were married in 1870. Cosima – a formidable woman – kept Wagner on a short leash throughout their marriage, but protected his interests, and enabled him to compose in peace.

Bayreuth

In June 1868 Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg – a blend of comedy, philosophy, radiant young love, arid wisdom as embodied in the person of Hans Sachs the cobbler – had been premiered in Munich. At the same time, Wagner continued working on his Ring cycle, but realized that no existing theater was suitable for such a large project. With King Ludwig's help, he raised the money to build a dedicated "Festival Theatre" at Bayreuth, where his operas are still performed at an annual festival directed by members of the Wagner family. The new theater was inaugurated in August 1876 with three complete performances of the Ring cycle of four works Das Rheingold, DieWalküre, Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung (The Twilight of the Gods).

Der Ring des Nibelungen – which contains over 12 hours of music is held together by a complex system of musical references called leitmotifs, in which characters and situations are identified by individual musical motifs, such as the joyous horn call associated with the hero Siegfried. By now Wagner's musical language had succeeded in merging voices and orchestra into one continuous texture, at the opposite end of the spectrum fom the Italianate concept of opera as separate arias, ensembles, and choruses. This complex, endlessly evolving web of sound proved an ideal vehicle for the grandiose Nibelung drama, which reaches its shattering conclusion as Valhalla burns and the world ends.

In 1882 Wagner finished his last opera, Parsifal, based on the quasi-religious myth of the quest for the Holy Grail, with its miraculous powers of healing. It was performed at Bayreuth in the summer of 1882, conducted by Hermann Levi, Wagner himself conducted the last scene of the final performance. Two weeks later, suffering from a heart condition, he took his family to Venice, where he died of a heart attack on 13 February 1883.

Major works

Die fliegende Holländer (1841); Tannhäuser (1843); Lohengrin (1848); Tristan und Isolde (1859); Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg (1867); Der Ring des Nibelungen (1853–1874); Parsifal (1882).