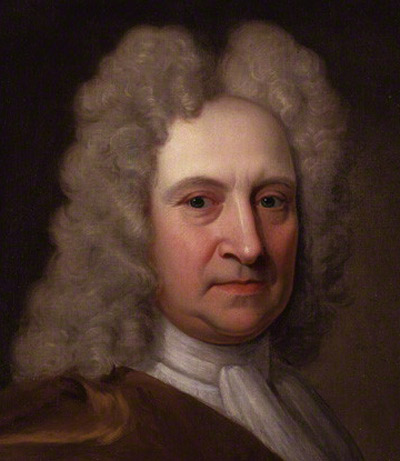

Halley, Edmond (1656–1742)

Edmond Halley was a highly influential and well-liked English astronomer and physicist best known for the comet named after him (see Halley's Comet). In 1679 he published the first accurate southern sky catalogue based on his two years of telescopic observations on St. Helena.

Halley's interest in comets was sparked by the great comet of 1682, which prompted him to work out the orbits of 24 known comets. Noting that the orbits of comets seen in 1456, 1531, 1607, and 1682 were very similar, he concluded that they were of one and the same object and predicted its return in 1758 (though he died before his prediction could be verified).

In 1695, after a decade of lunar studies, Halley proposed the secular acceleration of the Moon. In 1718, by noting that Sirius, Procyon, and Arcturus had changed position since the time of Ptolemy's Almagest, he discovered stellar proper motion.

After succeeding John Flamsteed as the second Astronomer Royal in 1720, Halley began a series of lunar and solar observations that spanned the 19-year lunar cycle, or Saros, and confirmed the Moon's secular acceleration. His celebrated friendship with Isaac Newton enabled him to persuade Newton to publish the Principia through the Royal Society, of which Halley served as clerk and editor. When the Society was unable to pay for the book's printing, Halley financed it himself. Among his other achievements, he proposed a way of determining the Earth-Sun distance by measuring transits of Venus (a method successfully used after his death), he realized that the aurora borealis was magnetic in origin, improved understanding of the optics of rainbows, raised the problem of what became known as Olber's paradox, and devised and personally used the first diving bell.