comet

Comet NEAT (C/2001Q4).

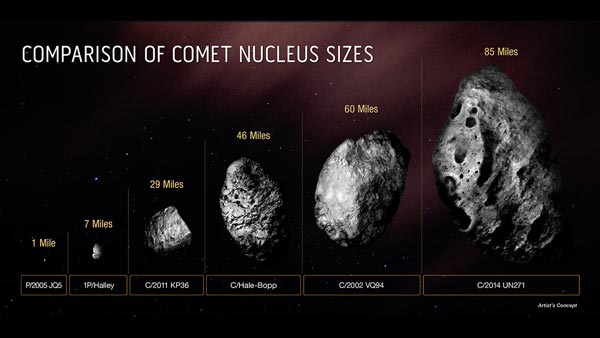

Figure 1. Comet structure.

Figure 2. Artist's impression of a comet's nucleus.

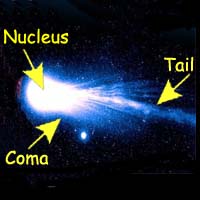

Figure 3. The size of the nuclei of comets varies widely.

A comet is a small astronomical body, typically a few kilometers across, that orbits the Sun. Comets contain icy chunks and frozen gases with bits of embedded rock and dust, and possibly a rocky core, aptly described as a "dirty snowball."

Comets are leftovers from the formation of the Solar System and are believed to exist in vast numbers in the Oort Cloud and, to a lesser extent, in the Kuiper Belt. From these regions they can be perturbed by the gravitational influence of passing stars or interstellar clouds and thrown into new, highly elliptical orbits (see ellipse) that bring them into the inner Solar System.

Historical introduction

In Greco-Roman times it was generally believed that comets were phenomena restricted to the Earth's upper atmosphere. In the late 15th and 16th centuries it was shown by M. Mästlin and Tycho Brahe that comets were far more distant than the Moon. Isaac Newton interpreted (incorrectly) the orbits of comets as parabolas, deducing that each comet was appearing for the first time. It was not until the seventeenth century that Edmund Halley showed that some comets returned periodically.

Parts of a comet

As a comet draws nearer to the Sun, solar radiation causes the comet's frozen gases to sublime (turn directly from a solid into a gas) and be released, so that, in addition to the frozen nucleus, several new features develop. These include a coma, a luminous cloud of water vapor, carbon dioxide, and other neutral gases driven off the nucleus; a hydrogen cloud, a huge (millions of kilometers in diameter), tenuous envelope of neutral hydrogen; a dust tail (the most prominent part of a comet to the unaided eye) up to 10 million kilometers long, composed of smoke-sized dust particles driven off the nucleus by escaping gases; and an ion tail, as much as several hundred million km long, composed of plasma and laced with rays and streamers caused by interactions with the solar wind (Figure 1).

Nucleus

A cometary nucleus is the central and relatively small part of a comet. It is often described as a "dirty snowball" since it is made up of about 75% ices (including frozen water, ammonia and carbon dioxide) and about 25% dust and rock (Figure 2). The sizes of known comet nuclei vary widely from around 1.5 kilometers across to 136 kilometers acrpss in the case of the largest one known – that of comet C/2014 UN271 (Bernardinelli-Bernstein) (Figure 3).

Coma

|

A coma is a glowing envelope of gas and dust that surrounds a comet's nucleus when the comet comes within a few astronomical units of the Sun (although Chiron has been seen to develop a coma at 11 astronomical unit (AU). At perihelion, the coma is typically about 100,000 kilometers across, and shaped into a teardrop by the solar wind. Together, the coma and the nucleus form the comet's head.

Types of comet

A comet that has been deflected into the inner Solar System from the Oort Cloud will have an incredibly elongated path, perhaps with a perihelion of 1 astronomical unit and an aphelion of 10,000 AU, so that it would take many centuries to return again; it might even approach on a hyperbolic path that will eventually carry it into interstellar space.

Many comets, however, are eventually nudged by close passages of the giant planets into smaller orbits which, although still elongated, bring them close to the Sun on a more regular basis. Of the two dozen or so comets that are seen each year through telescopes, the majority are short-period comets, with periods of less than 200 years, that are returning as predicted on well-known orbits or are new discoveries; the most famous of them is Halley's comet. The rest are long-period comets, seen for the first time, with periods of more than 200 years; among the brightest have been several Great Comets, the Daylight comet of 1910, and Donati's comet.

How a comet is named

When a newly discovered comet is confirmed, the International Astronomical Union assigns an interim designation consisting of the year of discovery followed by a lowercase letter in order of discovery for that year. Often the discoverer's name precedes the designation; for example, Comet Bennett 1969i. If a reliable orbit is later established, the comet is given a permanent designation consisting of the year of perihelion passage followed by a roman numeral in order of perihelion passage; for example, Comet Bennett 1970 II. If the comet is periodic, the letter P followed by the discoverer's (or computer's) name is used, as in comet 1910 II P/Halley.

Astrochemistry and astrobiology of comets

Apart from their rocky content, comets are made mostly of water-ice, plus frozen methane, ammonia, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide. They also contain an interesting collection of organic chemicals, including methanal (H2CO), hydrogen cyanide (HCN), and methyl cyanide (CH3CN), which are believed to have formed in interstellar space and then become incorporated into comets in the early development of the solar nebula.

These organic substances, and possibly others of greater complexity, would have been delivered to Earth's surface in significant amounts by impacting comets between about 3.5 and 4.5 billion years ago. Astrobiologists have conjectured that such material could have played an important role in the early development of life on Earth and elsewhere (see life, origin). Subsequent collisions between Earth and both comets and asteroids may have been a major factor behind mass extinctions and evolutionary surges (see punctuated equilibrium), such as that which led to the appearance of man (see cosmic collisions, biological effects).

Some researchers, notably Fred Hoyle and Chandra Wickramasinghe, have arguedthat life itself may have been seeded on Earth through cometary collisions and that, even now, pathogens regularly rain down on our planet as Earth sweeps through dusty comet tails, giving rise to global epidemics (see epidemics, from space). Although these ideas have received scant support from the scientific community at large, it is becoming increasingly apparent that comets have influenced the development of terrestrial life and may even have helped to instigate it.

Comets and meteor showers

A comet also contains dust particles which, after being released around the time of perihelion, contribute to the zodiacal cloud and also spread out along a comet's orbit, giving rise to annual meteor showers.

Families of comets

As well as the many individual comets on record, two distinct comet families are known: the Jupiter family, whose members have different origins but have all been captured by Jupiter into similar orbits, and the Kreutz family of sungrazing-comets, which may be fragments of a single parent body. Long-period comets and Halley-type comets are thought to have originated in the Oort Cloud at the limit of the Sun's gravitational domain. On the other hand, Jupiter-type comets, which are a category of short-period comet, appear to have come from the Kuiper Belt beyond the orbit of Neptune.

Exploration of comets by space probes

A number of space probes have already conducted investigations of comets, including Giotto, Deep Space 1, Stardust. Future encounters will involve Rosetta and Deep Impact.