textiles

Figure 1. Some cotton products.

Figure 2. Flax and jute products.

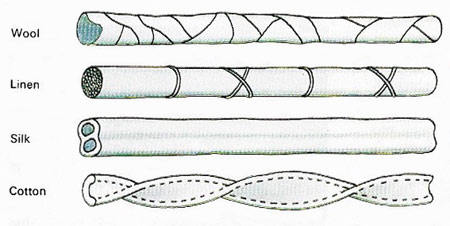

Figure 3. Wool, linen, silk, and cotton are the four main natural fibers.

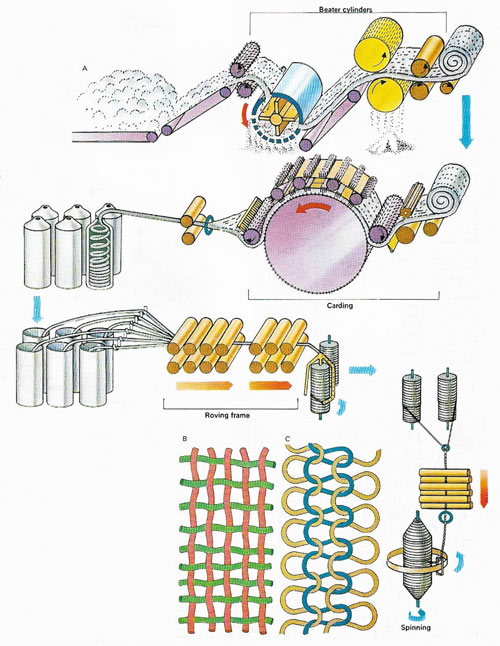

Figure 4. Each of the main fibers are sorted and spun by largely the same processes. After the raw material has been cleaned it is "opened" or arranged into a thick mat by passing it through a beater cylinder. It is then "carded" or combed by huge rollers covered with wire teeth. The tangled fibers are straightened into a thin web of lint, which is next condensed to slivers, which look like loose ropes of yarn. Each sliver is drawn, under tension, through rollers and coiled on to a roving frame. The "roving" is twisted and retwisted, becoming continually finer and stronger, before it is finally wound as finished yarn on to a bobbin. From the bobbin the yarn can be woven or knitted to make a fabric.

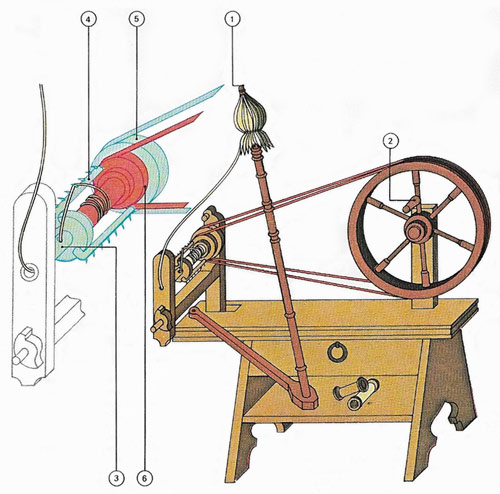

Figure 5. In this spinning wheel 0f 1480 the yarn is pulled from the distaff (1) by the left hand, while the right hand turns the wheel (2).The yarn passes through a hollow spindle (3) and hooks over a flyer (4) mounted on the spindle and driven by a pulley (5). The spool also turns on the spindle but is attached to a smaller pulley (6) which turns faster, so that the flyer twists the yarn at the same time as it is wound on to the collecting spool.

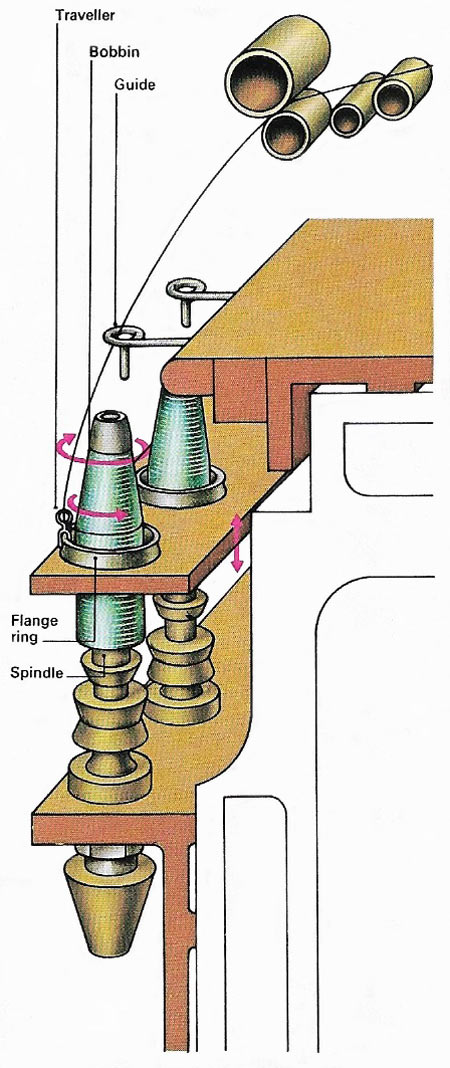

Figure 6. The ring spinning frame, invented by John Thorpe, is used for cotton. The yarn passes through a series of rollers and a guide, and finally down to the spindle. The flyer is replaced by a small traveller that runs freely on a flange ring which surrounds the spindle. The flyer is replaced by a small traveller that runs freely on a flange ring which surrounds the spindle. The bobbin is carried on the spindle and rotates very quickly. The traveller is pulled round the flange ring by the yarn and, because of the friction occurring between the traveller and the ring, the traveller lags behind the bobbin so that the yarn is wound on as it is spun. The plate holding the flange ring and traveller rises and falls, distributing the yarn evenly on the bobbin.

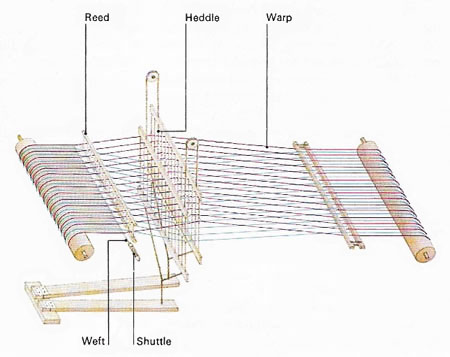

Figure 7. In the first looms, weaving proceeded like darning, the weft being passed over and under the warp. In other early looms every other warp thread was attached to a stick, the heddle, which could be lifted to part the warp allowing passage of the weft thread. The heddle eventually gave way to a device called the shaft, which parts the warp threads in various combinations to allow the weaving of patterns.

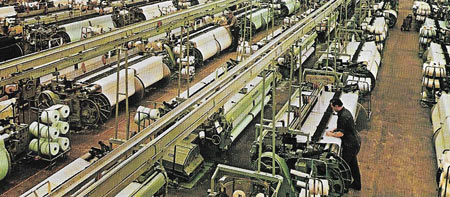

Figure 8. A modern textile factory generally has a number of looms all working at the same time. A machine minder tends one or machines, joining any broken yarn and supplying the loom with full bobbins. The strength and elasticity of yarn varies with temperature and amount of moisture in the air and so the whole room is air-conditioned to keep breakages to a minimum and stabilize the settings of the fine controls of the high-speed machine.

A textile is a flexible material made from natural or synthetic fibers, whether knitted, woven, bonded, or felted. Archaeological evidence from caves in Mexico and the American southwest reveals that fibers were already being used more than 10,000 years ago. Apart from using flax, jute, hemp, and other fibers to make ropes, nets or sacks, early man made crude fabrics by pounding the fibrous tissues of certain trees and plants into flat sheets of “bark-cloth”, such as the Polynesian tapa still made today. By 3000 BC cotton was being spun into yarn and woven into cloth (Figure 1) in India while the manufacture of linen (from flax) was well developed in Egypt even earlier.

|

| Flax. Linum sp. |

Types of fibers

Plant fibers

Fibers from different parts of a plant have varying characteristics. Bast fibers come from the inner tissues beneath the bark of dicotyledons (plants having two seed leaves). Made up of long overlapping cells, they are bedded in a cementing material that must be removed before the fibers can be peeled apart. Bast fibres are known as "soft tissues" and are particularly flexible. They can be made into rope or twine or woven into coarse, heavy-duty sacking. Jute, hemp, and flax are most commercially important and flax can also be woven into a soft, fine fabric known as linen. Sisal is a fiber taken from the leaf of the agave plant (Agave sisalana).

By soaking, or retting, the long stems in water, the material binding bast fibers together is partially decomposed by microorganisms in the water. The stems are then beaten and passed through rollers that separate the softened fibers from the mucilaginous matter. Jute fibers are stripped away by hand. Leaf fibers, mostly obtained from perennial plants, are part of the vascular structure of leaves. They have a stiff texture and are much shorter than bast fibers. In a process called decortications, rolling machines crush the leaves, scrape off non-fibrous matter and wash it away with jets of water. These "hard fibers" are generally too stiff to be made into fabrics. Their major use is as cord, twine, brush bristles, sacking, and carpet backing. The most important leaf fibers are sisal, henequen, and abaca.

Seed fibers grow as fine hairs on the seeds of certain plants. Each individual fiber is a single, elongated cell. Cotton, coir, and kapok are the only seed fibers of any major commercial value. Of the three, only cotton is suitable for spinning into fine yarn. Indeed, cotton and linen are the only vegetable fibers widely used for textiles. Kapok is mainly used as stuffing or insulation, and coir is made into ropes, sacks, and brushes.

Animal fibers

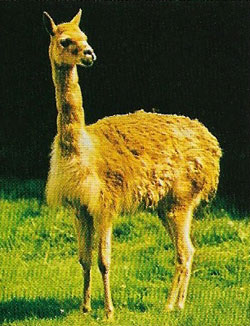

Wool is the best known animal fiber. Wool fabrics have low strength but are uniquely comfortable and warm because of the soft, springy fibers trap air, which insulates the wearer against cold. The main source of wool is the sheep, but some of wools come from goats. Cashmere is a fine fabric made from the fleece of the Kashmir goat living in China, Iran, and Mongolia. Mohair is a high-quality cloth made from the wool of the Angora goat, also a native of Asia. Fine, soft wools also come from members of the camel family – the llama, alpaca, guanaco, and vicuna, all of which live in South America. Wool, like other kinds of animal hair, is composed mainly of keratin, a fibrous protein also found in skin, nails, feathers, and horn. It is one of the few fibers that can be matted together into felt, or fuzz. This matting process adds to its softness. All wools, however, have the major disadvantage of vulnerability to attack by pests such as moths.

|

| The dense coat of the vicuna (Lama vicugna) protects it from the cold of the high Andes, where it lives at altitudes of 4,270 meters (14,000 feet). A vicuna is a South American member of the camel family and its wool is valued for its high quality. |

Silk, the only other animal fiber of importance, has long been used to make fabrics of delicate lustre and smoothness. Because of its cost, however, it has largely been superseded by synthetic fibers. The home of silk production is the Far East where silkworms, fed on mulberry leaves, eventually spin a continuous silk thread up to 800 meters (0.5 mile) long to make a cocoon.

The methods used in spinning, weaving and knitting natural fibers into fabrics are all very similar to one another (Figure 4).

Synthetic fibers

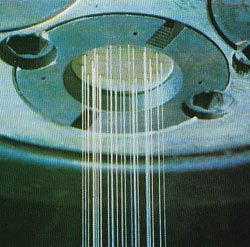

|

| Spinnerets are finely perforated plates or tubes that make threads from chemical solutions of polymers during the course of manufacturing all man-made fibers.

|

Synthetic fibers are now used to make a variety of fabrics and other products. The first to be developed, which came to be known as rayon, is composed of reconstituted, regenerated, and purified cellulose obtained from plants. It was originally produced, in the late nineteenth century as a substitute for silk. The cellulose, derived primarily from wood pulp, is chemically converted into a soluble compound. A chemical solution of the cellulose is then pumped through a spinneret (named after the silkworm's spinning gland) into a precipitant in which it coagulates into fine threads. These threads are then twisted together to make the rayon yarn, Another cellulose fabric is acetate rayon, the fibers of which are made by treating cellulose with acetic and sulfuric acids. The fibers of cellulose acetate are also made through a spinneret. Rayons die easily and they also lose their strength when wet, only to regain it when dry.

The second and much larger group contains the purely synthetic fibers – nylon and polyesters known by such trade names as Terylene and Dacron. The materials for these fabrics are made entirely from chemicals (often by-products of petroleum).

Spinning plastics into fibers often involves melting and extrusion through a spinneret. For plastics that are sensitive to heating, including the acrylics used to make such fabrics as Acrilan, it may be necessary to dissolve the plastic before spinning the fiber. Acrylic fibers have a soft, wool-like feel and often used for making blankets and winter clothing.

Manufacture of textiles

Natural fibers are prepared and spun (see spinning) into yarn. This is then formed into fabric by weaving or other methods. Finishing processes include bleaching; calendering; mercerizing; dyeing (see dye), brushing, sizing, fulling, and tentering. Chemical processes may be used to impart crease-resistance, fireproofing, stain-resistance, waterproofing, or non-shrink properties.

Preparation of fibers

The preparation of fibers involves a number of processes. For cotton these include brushing fibers from the seed bolls in a cotton gin; beating the fibers to loosen them; rolling or lapping them flat and scutching (beating) them into fleecy masses. All of these processes are now carried out completely by machines.

Carding and combing

Carding is a process used in textile manufacture whereby the fibers are laid out parallel to each other, then gathered into loose strands (card slivers) about 25 millimeters (1 inch) thick. The longest fibers only are used for high-quality yarns and are obtained by combing them out on a machine in which the fibers are held by rows of pins. The slivers are then drawn through a series of rubber rollers, each pair of which moves quicker than the previous pair so that the fibers elongate to form rovings. These rovings are then ready for spinning.

Washing and retting

Wool needs to be washed in detergent to remove dirt and grease. Fine worsted wool yarns use on the longest fibers, selected by a combing operation. Retting is the name of a treatment for flax fibers (for linen) in which they are rotted in water to soften them. Silk comes from the cocoon of the silkworm and requires a special treatment with soap or detergent to remove the gum that originally bound the filaments in the cocoon.

Spinning

Spinning is the ancient craft of twining together fibers from a mass to form strong, continuous thread suitable for weaving. The earliest method was merely to roll the fibers between hand and thigh. Later two sticks were used: the distaff to hold the bundle of fibers, and a spindle to twist and wind the yarn.

Mechanization began with the spinning wheel, invented in India and spreading to Europe by the fourteenth century. The wheel turned the spindle by means of a belt drive. In the 15th century the flyer was invented: a device on the spindle shaft that winds the yarn automatically on a spool (Figure 5).

Improved weaving methods in the Industrial Revolution caused increasing demand which provoked several inventions. The spinning jenny, invented by James Hargreaves (c. 1767), spun as many as 16 threads at once, the spindles all being driven by the same wheel. Richard Arkwright's water frame (1769), so called because it was water-powered, had rollers and produced strong thread. Then Samuel Crompton produced a hybrid of the two – his mule – which had a movable carriage, and was the forerunner of the modern machine. The other modern spinning machine is the ring-spinning frame (1828) in which the strands, drawn out by rollers, are twisted by a "traveler" that revolves on a ring around the bobbin on which they are wound.

In spinning, the rovings are passed to rotating spindles carrying bobbins, all mounted on a moving frame of the kind originated by Crompton. The frame first moves outward, pulling out the roving to form a yarn and twisting it. Then it moves back and the yarn is twisted evenly on to the bobbins, guided by the wires. Worsted and cotton are now usually spun on a ring spinning frame invented in 1828 by John Thorpe in the United States (Figure 6).

Linen is spun on a flyer frame that has a hollow inverted U-shaped device, the flyer, that is mounted on a spindle. Each yarn passes to a bobbin through the inside of this flyer which rotates round the bobbin, twisting the yarn as it does so.

Formation

When two or more yarns are interlaced in the process of weaving, carried out on a loom, a length of cloth is made. But when a single continuous length of yarn is looped into a fabric the operation is called knitting. Industrially, knitting is also carried out on machines.

Lace fabrics are made by interlacing and twisting yarns together. Felt fabrics are exceptional in that they are not knitted or woven. They are made by pounding hot, wet wool and other fibers together. The soft feel of "cut velvet" is given by many tufts of severed yarn endings although "figured" velvet, also a woven fabric, is not cut.

Weaving

Weaving is making a fabric by interlacing two or more sets of threads. In "plain" weave, one set of threads – the warp – extends along the length of the fabric; the other set – the woof, or weft – is at right angles to the warp and passes alternately over and under it. Other common weaves include "twill," "satin," and "pile." In basic twill, woof threads, stepped one warp thread further on with each line, pass over two warp threads, under one, then over two again, producing diagonal ridges, or wales, as in denim, flannel, and gabardine. In satin weave, a development of twill, long "float" threads passing under four warp threads give the fabric its characteristically smooth appearance. Pile fabrics, such as corduroy and velvet, have extra warp or weft threads woven into a ground weave in a series of loops that are then cut to produce the pile.

Weaving is usually accomplished by means of a hand- or power-operated machine of loom. Warp threads are stretched on a frame and passed through eyelets in vertical wires (heddles) supported on a frame (the harness). A space (the shed) between sets of warp threads is made by moving the heddles up or down, and a shuttle containing the woof thread is passed through the shed. A special comb (the reed) then pushes home the newly woven line (Figure 7).

Finishing

Fabrics are finished in a number of operations that include bleaching, dyeing, and printing.

Bleaching

Bleaching is the process of whitening materials by sunlight, ultraviolet radiation, or chemicals that reduce or oxidize dyes into a colorless form. Hydrogen peroxide is used to bleach wool, silk, and cotton; hypochlorites, including bleaching powder (see below), are used for cotton; and sodium chlorite for synthetic fibers. Sulfur dioxide bleaches are impermanent. Careful control of pH is essential.

Bleaching powder

Bleaching powder is a white powder consisting of calcium hypochlorite and basic calcium chloride, made by reacting calcium hydroxide with chlorine. It is used for bleaching and as a disinfectant, but in time loses its strength.

Calendering

Calendering is a process used in the manufacture of textiles, rubber, some plastics, and especially high-grade quality paper. The substance concerned is passed between a series of pairs of heated rollers, which squeeze it to form a smooth textured sheet.

Dyeing and other finishing

Natural fibers, with the exception of silk, are easy to dye but special chemical processes are sometimes necessary to make dyes adhere to synthetics. Printing on cloth resembles that on paper: flat or cylindrical printing blocks or silk screen processes can be used.

The luster of a fabric, particularly cotton, can be improved in a number of ways, including singeing and mercerizing, a process using caustic soda. Wool fabrics are treated against shrinking by chemical treatment of the fibers. Natural fibers and rayon can be treated with resins to render them crease-resistant or an elastic plastic to make them waterproof and stain-proof.