Laplace, Pierre Simon de (1749–1827)

Pierre Laplace was a French physicist and mathematician who put the final capstone on mathematical astronomy by summarizing and extending the work of his predecessors in his five-volume Traité de Mécanique Céleste (Treaty on Celestial Mechanics), published from 1799 to 1825. This work was important because it translated the geometrical study of mechanics used by Isaac Newton to one based on calculus. In Mécanique Céleste, Laplace proved the dynamical stability of the Solar System (with tidal friction ignored) on short timescales. Over long periods, however, this assertion has proven false because of the effects of chaos. Laplace explained the long-term variations in the orbital speeds of Jupiter and Saturn (1786), and the Moon (1787). His nebular hypothesis of the origin of the Solar System (1796) is similar to that of Immanuel Kant, of which he was apparently unaware.

The Solar System, Laplace said, originated out of a gradually cooling cloud of gas, with the planets most remote from the center condensing first. This theory had a strong influence on subsequent speculation about the nature of our neighboring worlds. It implied that the inner worlds were younger and that, in particular, cloud-covered Venus might be an immature version of the Earth – a virgin world. By contrast, planets further from the Sun, such as Mars, would have formed later and therefore could be expected to be more highly evolved. Laplace's theory also suggested that planets are a natural consequence of the evolution of stars, so that many stars ought to have planetary retinues. It therefore provided powerful support for the doctrine of pluralism. After reading Mécanique Céleste, Napoleon Bonaparte is said to have questioned Laplace on his neglect to mention God. In contrast to Newton's view on the subject, Laplace replied: "Sir, I have no need of that hypothesis."

Laplace's equation

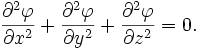

Laplace's equation is a partial differential equation named after its discoverer. The solutions of Laplace's equation are important in many fields of science, notably electromagnetism, astronomy, and fluid dynamics, because they describe the behavior of electric, gravitational, and fluid potentials.

In three dimensions, the problem is to find twice-differentiable real-valued functions φ of real variables x, y, and z such that

Solutions of Laplace's equation are called harmonic functions.

Gambler's fallacy

If, when using a fair coin, heads are flipped five times in a row, the gambler's fallacy suggests that the next toss will be tails because it is "due", the chance of tails coming up on the next toss is therefore seen as greater than half. This is bad reasoning because the results of previous tosses have no bearing on future tosses. Laplace first noted the fallacy behavior in his Philosophical Essay on Probabilities (1796), in which he wrote about expectant fathers trying to predict the probability of having sons. The men imagined the ratio of boys to girls born each month to be fifty/fifty, and that if neighboring villages had high male birth rates it implied that births in their own village had a high probability of being female. Also, fathers who had several children of the same sex believed that the next one would be of he opposite sex – it being due.

The fallacy is also known as the Monte Carlo fallacy because of an incident that happened there at a roulette table in 1913, when black fell 26 times in a row. While this is a rare occasion, it is among the possibilities, as is any other sequence of red or black. Needless to say, gamblers at that table lost millions that day because they reasoned, incorrectly, that red was due to be next, or next after that. The fallacy also occurs in the erroneous thought that gambling is an inherently fair process, in which any losses incurred inevitably will be corrected by a winning streak. The gambler's fallacy warns that there is no Lady Luck or "invisible hand" in charge of your game.