thorax

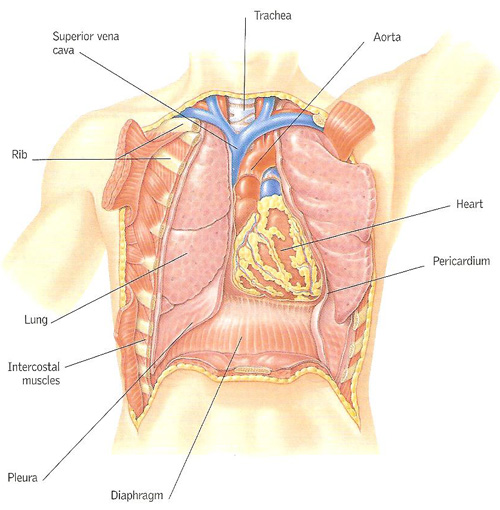

Figure 1. The thoracic cavity. The organs within the thoracic cavity are protected by the framework of the ribs. Thin membranes (plurae) surround the lungs to prevent friction during breathing; a membranous sac, the pericardium, protects the heart.

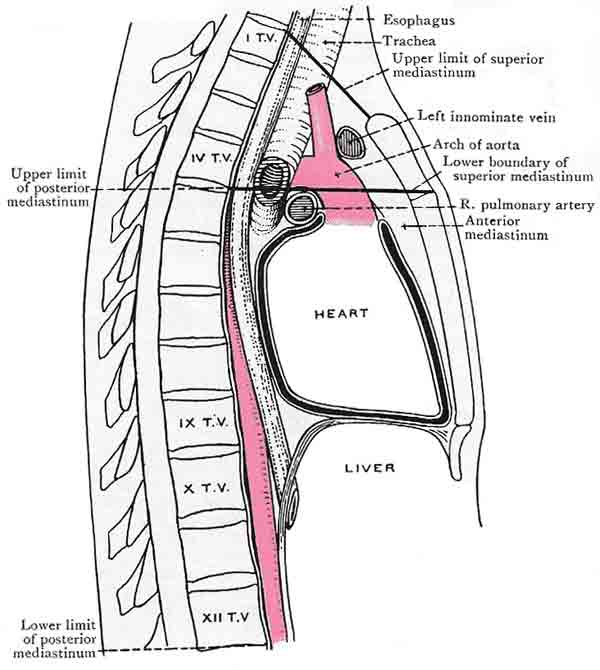

Figure 2. The heart and pericardium occupy the middle mediastinum. The pericardium forms the osterior boundary of the anterior mediastinum and part of the anterior boundary of the posterior mediastinum.

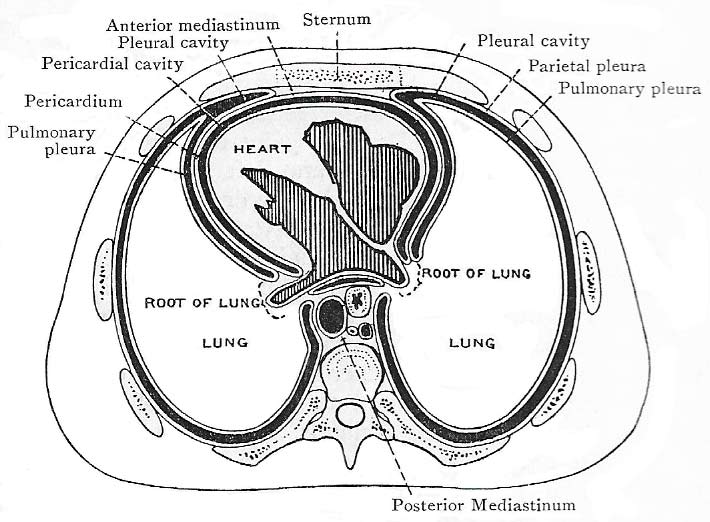

Figure 3. Transverse section of the thorax.

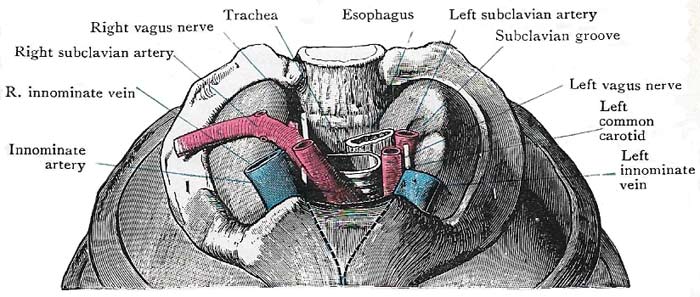

Figure 4. The inlet of the thorax and its principal contents.

The thorax is the upper area of the trunk, known commonly as the chest. It extends from the base of the neck to the diaphragm, which separates the thorax from the abdominal cavity. Within the thoracic cavity, walled by the ribcage and its associated muscles, are the heart and lungs, and the body's major blood vessels and airways (Figure 1). A section of the trachea and esophagus are also in the thorax.

Shape and framework of the thorax

The form of the thorax is that of a truncated cone, flattened in front and behind but rounded at the sides.

The framework of the walls is formed anteriorly by the sternum and the costal cartilages; posteriorly by the bodies of the 12 thoracic vertebrae and the corresponding intervertebral disks, and by the ribs, from their heads to their angles; and on each side by the shafts of the ribs, from their angles to their cartilages.

The anterior wall is so much shorter than the posterior wall that, during expiration, the upper margin of the sternum is opposite the disk between the second and third thoracic vertebrae, and the xiphisternal joint is opposite the ninth or the tenth thoracic vertebrae (Figure 2).

The bodies of the thoracic vertebrae project forwards and greatly diminish the anteroposterior diameter of the cavity in the median plane; but the backward sweep of the posterior parts of the ribs produces a deep hollow on each side of the vertebral column for the reception of the most massive part of the corresponding lung (Figure 3).

Inlet and outlet

The inlet of the thorax (Figure 4) is a narrow opening which is bounded by the body of the first thoracic vertebra, the first pair of ribs and the upper border of the manubrium sterni. The plane of the inlet slopes very obliquely downwards and forwards, so that the anterior part of the apex of the lung is above the level of the anterior boundary of the inlet, though its posterior part only attains the level of the neck of the first rib (Figure 4).

The structures which enter or leave the thorax through the inlet are: the trachea; the esophagus (or gullet); the vagus and the phrenic nerves on each side; the left recurrent laryngeal nerve; the thoracic duct; and the great arteries and veins which carry blood to and from the head and neck and upper limbs.

The outlet of the thorax is much larger than the inlet. It is bounded by the xiphisternal joint, by the lower six costal cartilages and the twelfth rib, and by the twelfth thoracic vertebra; and the boundary or margin is curved, for it descends to the tip of the eleventh costal cartilage and then ascends.

The inner aspect of the lower margin of the thorax gives attachment to the diaphragm, which forms a convex floor for the thorax and a concave roof for the abdomen. By its upward bulging it greatly diminishes the vertical diameters of the thorax; and the result of this arrangement is that the margin of the lower part of the thorax overlaps the upper part of the cavity of the abdomen, especially at the sides and behind.

The diaphragm, however, is not an unbroken partition. There are three large openings in it through which structures pass between the thorax and the abdomen, namely, aortic, esophageal, and vena caval. The aortic opening transmit: :the great artery called the aorta as it descends from thorax to abdomen; the thoracic duct – the chief lymph vessel of the body – ascending from the abdomen; and frequently a vein named the vena azygos, also ascending from abdomen. The esophageal opening transmits the esophagus with the two gastric nerves – the continuation into the abdomen of the vagus nerves. The vena caval opening transmits the largest vein in the body – the inferior vena cava. In addition, there are smaller apertures that transmit structures.

The thorax in other animals

As far as animals in general go, the thorax is the anterior region of the trunk. In vertebrates, the thorax is the region of the body containing the heart and lungs within the rib cage. Only in mammals is it clearly marked off from the abdomen by the diaphragm.

In insects, the thorax is the second body region, located between the head and abdomen. It is the region where the legs and wings are attached. In other arthropods, especially crustaceans and arachnids, the thorax is fused with head to form a cephalothorax.

Thoracotomy

An operation in which the chest is opened to provide access to organs in the chest (thoracic) cavity.

There are two types of thoracotomy: lateral and anterior. In a lateral thoracotomy the chest is opened between two ribs to provide access to the lungs, major blood vessels, and the esophagus. In an anterior thoracotomy, an incision down the length of the sternum (breastbone) provides access to the heart and the coronary arteries.