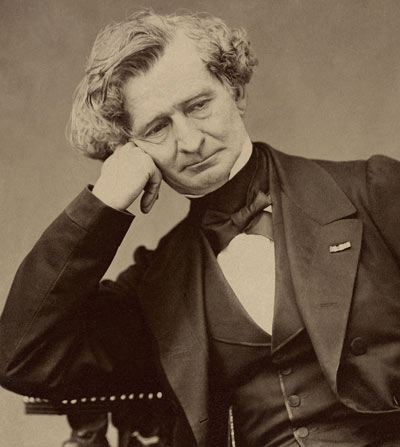

Berlioz, Hector (1803–1869)

Portrait of Berlioz by by Pierre Petit, 1863.

Harriet Smithson as Ophelia. Berlioz became obsessed with her and eventually married her, with disastrous consequences.

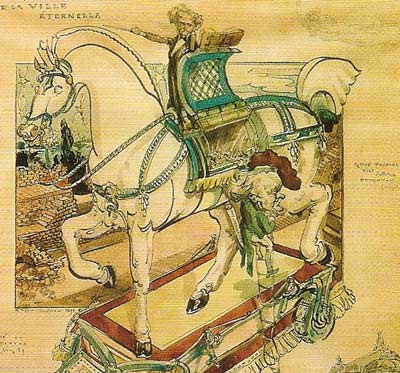

Caricature of Berlioz conducting, by Georges Tiret-Bognet.

Like Schumann and Chopin, Berlioz is regarded as an archetypal Romantic artist, both for the nature of his work and for the colorful events of his life, which are documented in his entertaining Memoirs.

The son of a provincial French doctor, he intended to pursue a medical career, but the grisly scenes of carnage he encountered at medical school in Paris put him off. Instead he began music lessons, first privately and then at the Paris Conservatoire.

Sensitive, passionate, and impulsive by nature, Berlioz was prone to violent emotions. In 1827 he saw an English theater company performing Hamlet at the Odeon Theatre, and was immediately stricken with wild admiration, both for Shakespeare and for Harriet Smithson, the attractive Irish actress who played Ophelia. His unrequited passion found an outlet in 1830 in the extraordinary, programmatic Symphonie fantastique, subtitled "Episodes in the life of an artist". In the first three of its five movements, "the beloved" appears in various transformations as a melodic motif (which Berlioz called the idée fixe), whether in "passions and dreams", at a ball, or during a pastoral idyll (which owes much to Beethoven). In the fourth movement, "March to the Scaffold", the artist dreams that he has murdered his beloved and is being led to the guillotine; in the last, a grotesque witches' sabbath, the beloved has been transformed into a hag, her theme obscenely distorted.

In 1832 Berlioz finally persuaded Harriet Smithson to marry him. But proximity to the Beloved proved less appealing than worship from afar. Although he never divorced Harriet (who died of alcoholism in 1854), he formed a liaison from 1841 onwards with the singer Marie Recio, who later became his second wife.

During the 1830s Berlioz produced some of his finest works, including the symphony with obbligato viola, Harold en Italie. This work was commissioned by Paganini, who paid the struggling composer 20,000 francs for the piece, although he never played the solo part because he said it did not adequately display his talents as a virtuoso.

Large-scale works

Berlioz's predilection for the monumental led him to compose enormous scores for huge orchestral forces (although he himself played only the guitar, he was a master of orchestration and wrote an influential treatise on the subject). His colossal works for chorus and orchestra included a Requiem (1837), the dramatic symphony Roméo et Juliette (1838–1839), the Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale (1840), and the operas Benvenuto Cellini (1834–1837), and Les Troyens (TheTrojans, 1856–1858).

Berlioz never had enough money. He was forced to supplement his income by working as a music critic and by touring Europe as a conductor. In 1846 Le damnation de Faust, a "dramatic cantata" based on the play by Goethe — whom Berlioz declared, together with Shakespeare, the guiding influence of his life — failed to attract attention in Paris, though it scored a great success in Russia. But his oratorio L'enfance du Christ (The Childhood of Christ) achieved a modest success in 1854, and the exquisite "Shepherds' Farewell" scene has always remained a popular favorite.

Le Troyens finally reached the stage in 1863, when the second part only, Les Troyens à Carthage, was performed in Paris. Its failure broke Berlioz's heart, and his last years were clouded by depression and ill-health. (The opera was not staged in its entirety in French until 1969.) In the early 1860s he completed his last work, the sparkling Shakespearean opera Béatrice et Bénédict, but thereafter wrote little until his death.

Re-evaluation

While his large-scale works are still performed relatively infrequently because they are so expensive to mount, the Symphonie fantastique and the concert overtures (especially Les francs-juges, the Byronic Le corsaire, and Le carnaval romain) have remained popular, as has the delicately scored orchestral song-cycle, Les nuits d'été (Summer Nights, 1841), based on a series of poems by Théophile Gautier.

Berlioz is still perceived as an oddball composer, and his originality has been derided as incompetence. But the persuasive advocacy of writers such as David Cairns and conductors such as Colin Davis and Roger Norrington have restored some previously neglected masterpieces, such as Les T royens, to the repertoire, and affirmed Berlioz's importance as one of the foremost 19th-century composers.

Major works

Symphonie fantastique (1830); Harold en Italie (1834); Grande messe de morts (1837); Roméo et Juliette (1838–1839); overtures Le corsaire (1831) and Le carnaval romain (1844); La damnation de Faust (1846); Te Deum (1849); Les Troyens (1856–1858).