Schumann, Robert (1810–1856)

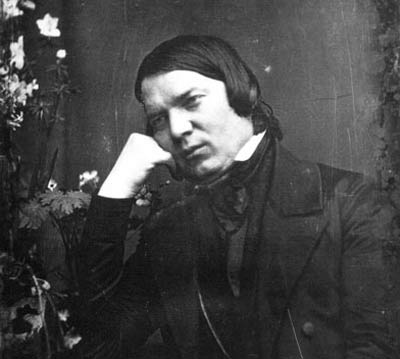

Robert Schumann in an 1850 daguerreotype

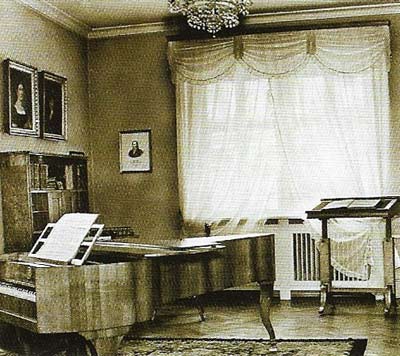

Schumann's study at his home in Zwickau

Robert Schumann in an 1850 daguerreotype

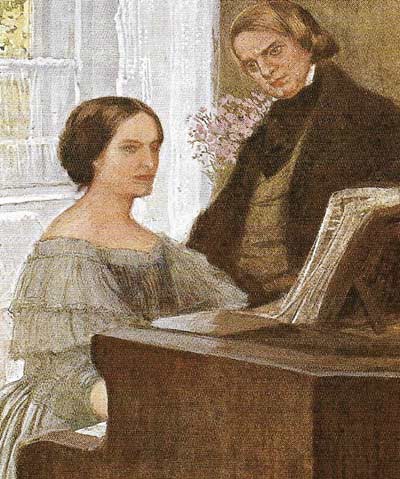

Clara and Robert Schumann. Their marriage in 1840 marked the beginning of a partnership that was rare for its time.

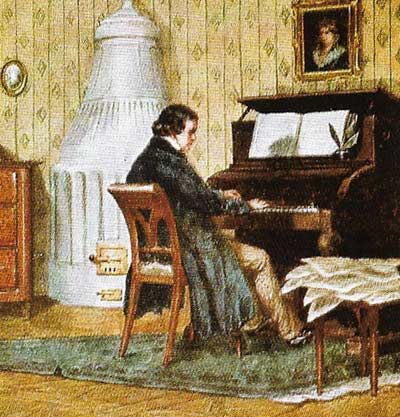

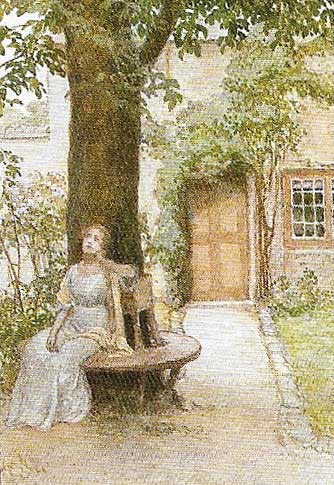

An illustration to Schumann's song "Der Nussbaum" ("The Walnut Tree"), No. 3 in the song-cycle Myrthen.

Robert Schumann was a German composer, pianist, and influential music critic, who is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. He was born in Zwickau, Saxony, on 8 June 1810.

Just as Mozart and Beethoven dominated the musical scene in e late 18th and early 19th centuries, Mendelssohn and Schumann were the standard-bearers until 1850. Schumann's personality and career exemplify musical Romanticism: his moody nature, fluctuating between exuberance and deep depression; his prolonged struggle to win the hand of his adored Clara; his receptiveness to literary stimuli, his obsession with numerology and secret ciphers, and finally his collapse into madness and early death, possibly as a result of syphilis (which, together with tuberculosis, put a premature end to many a flourishing Romantic talent).

Literary influences

Schumann was the youngest child of a bookseller, whose interest in literature he clearly inherited. While still a schoolboy he began to compose music, and also to write articles and drama. He formed a society for the study of German literature, and in the novels of Jean Paul (pseudonym of Johann Paul Richter, 1763–1825) he found a role model for the two conflicting sides of his own personality, which he later characterized as Florestan (extrovert and impetuous) and Eusebius (dreamy, melancholic, introverted).

While studying law in Leipzig he began to take piano lessons. with Friedrich Wieck, whose nine-year-old daughter Clara was showing extraordinarily precocious talent as a pianist. By now Schumann had decided to follow a career in music, but a hand injury (possibly a result of muscular weakness caused by mercury treatment for syphilis) put paid to his hopes of becoming a concert pianist. Instead, he decided to concentrate on composition and criticism.

Early works

By 1832 Schumann had published two major piano pieces, the Variations on the name "Abegg", based on a waltz theme derived from the name of a girl who had taken his fancy, and Papilions (Butterflies), a set of pieces linked by events at a masked ball described in a novel by Jean Paul. He also began work on a symphony.

In 1834 he founded the influential music periodical Neon Leipziger Zeitschrift für Musik, which he used to promote new musical talent, including Brahms and Chopin. He also used its pages to fight artistic philistinism by way of an imaginary society, the Davidsbund, or "League of David" (named after the vanquisher of Goliath), whose members were given fanciful names: Schumann himself was either Florestan or Eusebius; Clara Wieck was Chiara or Chiarina; her father was Master Raro, and Mendelssohn was Felix Meritis.These names appeared in Schumann's set of 18 "characteristic pieces" for piano, Davidsbündlertanze (Dances of the League of David, 1837).

Marriage to Clara

In 1834 Schumann fell in love with Ernestine von Fricken, to whom he became secretly engaged (and for whom he wrote the set of piano pieces later titled Carnaval). When he discovered that she was only the illegitimate daughter of a Baron, he broke off the engagement and transferred his affections to Clara Wieck, by now a delicate, dark-haired beauty of 15. Clara's father, who guarded his daughter jealously, was furious, and forbade Schumann to contact Clara. Then began an acrimonious six-year battle between Wieck – who made outrageous allegations against Schumann's character – and the lovers. Finally, in 1840, a court ruling paved the way for Schumann's marriage to Clara, which took place on 12 September.

Thus began one of the most remarkable musical marriages – a partnership far ahead of its time – in which both husband and wife tried to combine family life with successful, independent careers. Clara Schumann (1819–1896) was one of the most extraordinary women of her time. Her fragile appearance belied a steely inner strength, which enabled her to continue her demanding schedule of concert appearances all over Europe (she was one of the finest pianists of her age) while also coping with repeated pregnancies and child-rearing. While the marriage was not without its strains (Schumann resented his wife's success, which overshadowed his own reputation as a composer), Clara stimulated her husband's creative imagination, acting as muse, confidant, and critic.

Productive years

From 1840 onwards, almost in regular annual cycles, Schumann poured out song-cycles – including Myrthen (Bridal Wreath), his wedding present to Clara, Liederkreis ("song-cycle"), Frauenliebe und Liben (Woman's Lore and Life), and Dichterliebe (A Poet's Love) – chamber music (including a piano quartet and quintet, and three piano trios), and a body of piano music unsurpassed by any other contemporary composer. It was Clara who encouraged Robert to try his hand at larger-scale works. These included concertos for piano (the popular A minor Concerto was written for her), violin, and cello; four symphonies, and other symphonic works including the exuberant Konzertstück for four horns and orchestra and the Manfred overture, inspired by Byron.

Schumann's orchestral music has been criticized for heavy-handed orchestration (partly the result of his own ineptitude as a conductor), but any defects are amply compensated for by its melodic charm and ingenious construction. Schumann's innovations include the recurring use of motto themes and other cyclical devices: in the D minor Symphony (No. 4), he directed that the thematically linked movements should be played without a break.

His large-scale vocal works include the secular oratorio Das Paradies und die Peri (1843), one opera, Genoveva (1850), and choral music including Scenes from Goethe's "Faust" (1853). As a composer of songs and piano music, he proved himself a worthy successor to Schubert. His piano music encapsulates an enigmatic private world, full of literary and musical allusions, autobiographical references, and cryptograms: many of the piano pieces are built around references to Clara, such as the musical equivalents of the letters of her name. His songs include settings of Goethe, Adelbert von Chamisso (1781–1838), Eduard Mörike (1804–1875,) and Joseph von Eichendorff (1788–1857), but his settings of Heinrich Heine (1797–1856), particularly the Dichterliebe cycle and some of the Romanzen und Balladen, are unsurpassed for their subtlety and lyricism.

Final years

In 1843 the Schumanns were reconciled with Friedrich Wieck, no doubt anxious to see his first grandchild. After a concert tour of Russia the following year they moved from Leipzig to Dresden. Schumann had always been prone to fits of deep depression and ill-health, and in 1846 he was so beset by nerves and chronic illness that he composed very little. By 1849 (when a revolutionary insurrection forced the family temporarily to flee Dresden), Schumann was becoming disillusioned by his failure to find a real job, and in 1850 he accepted an offer to become municipal music director in Düsseldorf.

His years in Dusseldorf were marked by failing health and mental instability, which adversely affected his abilities as a conductor and caused increasing problems with his employers. He became obsessed with phenomena such as table-turning, and suffered aural and cerebral disturbances. Among the highlights of his later years were his meetings with the young Johannes Brahms, whom Schumann hailed in his magazine as a musician of the future, and the violinist Joachim, for whom Schumann wrote his Fantaisie for violin and orchestra and the Violin Concerto. Among his last compositions were the charming Phantasiestücke (Fairy-tales, 1849) for clarinet, viola, and piano, and five Romances (1853) for cello and piano.

Schumann's mental faculties finally gave way completely in February 1854, and he began to experience hallucinations. After a failed suicide attempt, he was committed to an asylum. During the two and a half years in which he was incarcerated there, he was not allowed to see Clara. She was finally summoned to his bed two days before his death on 29 July 1856.

Major works

Piano music including Carnaval (1835), Kinderszenen, Fantasie in C, and Kreisleriana (all 1838); about 250 songs, including song-cycles Dichterliebe, Frauenliebe und Liben (1840); four symphonies (No. 1 Spring, 1841, No. 3 Rhenish, 1850); Piano Concerto (1841–1845).