tracheostomy

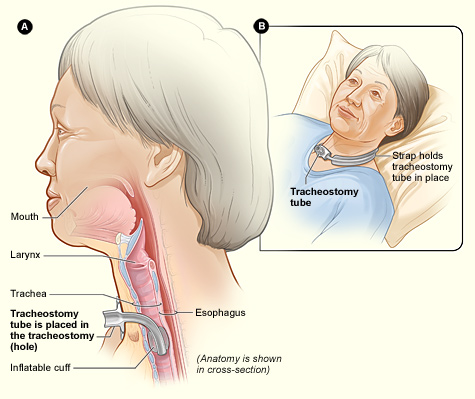

Fig A shows a side view of the neck and the correct placement of a trach tube in the trachea, or windpipe. Fig B shows an external view of a patient who has a tracheostomy.

A tracheostomy, also called a tracheotomy (or "trach"), is a surgically made hole through the front of the neck and into the trachea (windpipe) to help with breathing. It is usually temporary, although some are long term or even permanent. How long the tracheostomy remains in place depends on the condition that necessitated it and the patient's overall health.

Overview

To understand how a tracheostomy works, it helps to understand how the airways work. The airways are pipes that carry oxygen-rich air to the lungs. They also carry carbon dioxide, a waste gas, out of the lungs.

The airways include your:

Air first enters the body through the nose or mouth. The air then travels through the larynx and down the trachea, which splits into two bronchi that enter the lungs.

A tracheostomy provides another way for oxygen-rich air to reach the lungs, besides going through the nose or mouth. A breathing tube, also called a trach ("trake") tube, is placed through the tracheostomy and directly into the windpipe to help with breathing.

Tracheostomy is done for a number of reasons. Usually, it's done because

a person needs to be on a ventilator for more than 1 to 2 weeks. A ventilator is a machine that helps with breathing.

With a tracheostomy, the trach tube the patient to the ventilator.

A tracheostomy may also be need if a person has a condition that interferes

with coughing or blocks the upper airways. Coughing is a natural reflex

that protects the lungs. It helps clear mucus and bacteria from the airways.

A trach tube can be used to help remove, or suction, mucus from the airways.

Less often, people who have swallowing problems due to strokes or other conditions may have tracheostomies.

Outlook

Creating a tracheostomy is a fairly common, simple procedure. It's one of the most common procedures for critical care patients in hospitals.

Because the trachea is located almost directly under the skin of the neck, a surgeon often can create a tracheostomy fairly quickly and easily.

While the procedure to create a tracheostomy usually is done in a hospital operating room, it also can be safely done at a patient's bedside. Less often, a doctor or emergency medical technician may create a tracheostomy in a life-threatening situation, such as at the scene of an accident or other emergency.

The procedure generally is very safe, but it can lead to various complications, including bleeding, infection, and other, more serious problems. The risk of complications often can be reduced with proper care and handling of the tracheostomy and the tubes and other related supplies.

Some people continue to need tracheostomies even after they leave the hospital. Hospital staff will teach the patients and their families or caregivers how to properly care for their tracheostomies at home.

Who needs a tracheostomy?

People of all ages may need tracheostomies for various reasons.

People who are on ventilators

The most common reason for needing a tracheostomy is the use of a ventilator for more than 1 to 2 weeks. For people who are on ventilators and awake, a trach tube may be more comfortable than a breathing tube put through the nose or mouth and down into the windpipe. A trach tube also makes it possible for some people who are on ventilators to eat and talk.

Depending on the reason for needing a ventilator, a tracheostomy may be temporary or permanent. If a person need a ventilator for the rest of his or her life, the tracheostomy will probably be permanent.

If a doctor decides a patient is able to stop using the ventilator, the patient may no longer need the tracheostomy. The hole can then be allowed to close up, either on its own or with surgery.

People who have conditions that affect coughing or obstruct the airways

A tracheostomy may be needed if a person has trouble coughing. A trach tube can be used to help suction mucus from the airways.

A tracheostomy may also be needed if a patient has a condition that obstructs, or blocks, the upper airways.

Examples of diseases, conditions, and factors that may interfere with your ability to cough and/or block your upper airways include:

Some of these conditions are temporary. Once the patient recovers enough to breathe easily and safely on their own, they'll no longer need the tracheostomy. Other conditions may require a long-term or permanent tracheostomy.

People who have swallowing problems

People who have swallowing problems due to strokes or other conditions may have tracheostomies. The tracheostomies are used until they can swallow normally again.

Before a tracheostomy

The procedure to make a tracheostomy usually is done in a hospital operating room. However, it may be done at a patient's bedside. Rarely, a doctor or emergency medical technician will do the procedure in a life-threatening situation, such as at the scene of an accident or other emergency.

When a tracheostomy is done in a hospital, a general or pediatric surgeon or an otolaryngologist does the surgery. Otolaryngologists specialize in diagnosing and treating problems with the ears, nose, and throat and related structures of the head. These doctors also are called ear, nose, and throat (ENT) doctors.

A pulmonologist or intensive care doctor may help assess a patient's need for a tracheostomy. A pulmonologist specializes in diagnosing and treating lung diseases and conditions.

Often, doctors do tracheostomies on short notice, so there's little time for a patient to prepare. When possible, the surgical team may request that you fast (not eat anything) for 6 to 8 hours before the surgery.

People who are having tracheostomies are given general or local anesthesia before the procedure. The term "anesthesia" refers to a loss of feeling and awareness. General anesthesia temporarily puts you to sleep. Local anesthesia numbs the neck and surrounding area.

During a tracheostomy

To create a tracheostomy, a surgeon makes a cut through the lower front part of the neck, then makes a cut in the trachea. A trach tube is placed through the hole and into the trachea. The tube helps keep the hole open. Some trach tubes are "cuffed." Cuffed tubes can be widened or narrowed by inflating or deflating the cuffed part with air.

A chest X-ray may be done to make sure the trach tube is placed correctly. The tube will then be held in place with stitches, surgical tape, and/or a Velcro band.

Typically, the procedure to make a tracheostomy takes between 20 and 45 minutes.

After a tracheostomy

Depending on a patient's overall health, he or she may stay in the hospital for 3 to 10 days or more after getting a tracheostomy. It can take up to 2 weeks for a tracheostomy to fully form, or mature.

Patients may be sedated during their recovery. This means that they're given medicine to help them relax, and which may also make them sleepy.

Eating

Until the tracheostomy is mature, normal isn't possible. Instead of food, nutrients may be given through an intravenous (IV) line inserted into a vein. Alternatively, food may be supplied through a feeding tube which goes through the nose or mouth into the stomach. If a patient will be on a ventilator for a long time, the tube may be placed directly into the stomach or small intestine through a surgically made hole.

After the tracheostomy has matured, a patient will likely work with a speech therapist to regain the ability to swallow normally. The patient may have swallowing tests to show whether he or she can swallow safely; depending on the results, it may be possible to start eating normally again.

Communicating

Talking isn't possible right after the procedure. Even after the tracheostomy has matured, speaking remains problematic. The trach tube interferes with the normal voice process, preventing air from the lungs from flowing over the larynx.

However, once the tracheostomy has matured, a speech therapist or other health professional will show the patient ways in which the voice can be used to speak clearly. One option is a speaking valve that attaches to the trach tube. The valve lets air enter the tracheostomy, pass into the trachea and up over the larynx, and then exit the mouth or nose.

Certain types of cuffed trach tubes also can help with speech. Cuffed tubes can be widened or narrowed by inflating or deflating the cuffed part with air. When a person is using a ventilator, for example, the cuffed tube is inflated to fill the width of the airway. When a ventilator isn't being used, the tube can be deflated. This allows some air to enter the trachea and pass over the larynx.

Other concerns

If the tracheostomy is temporary and no longer needed, a doctor will remove the trach tube. This should allow the hole to close up on its own fairly quickly.

If the hole doesn't close on its own, the patient may have to have surgery to close it. A small scar at the site of the tracheostomy will remain.

Risks

A tracheostomy can put you at risk for a number of complications. Some complications are more likely to occur soon after the procedure is done. Others are more likely to happen over time. Some complications are mainly related to the presence of the trach tube.

The risk of complications often can be reduced with proper care and handling of the tracheostomy and the tubes and other related supplies.

Immediate complications

Complications that may occur shortly after surgery include:

Later complications

Over time, other complications may develop. For example, infections may scar the windpipe. A fistula, or abnormal connection, may form between the trachea and esophagus. (The esophagus is the passage leading from your mouth to your stomach.)

A fistula between the windpipe and esophagus can cause food and saliva to enter the lungs and possibly cause pneumonia. Symptoms of a fistula include severe coughing and trouble breathing.

Trach tube complications

The trach tube also can cause a number of problems. For example, the tube may accidently slip or fall out of the tracheostomy. Other complications include:

Living with a tracheostomy

You may still need a tracheostomy after you leave the hospital. If so, before you leave the hospital, hospital staff will show you and your family or caregiver how to care for the tracheostomy at home.

Proper care and handling of the tracheostomy and the tubes and other related supplies can help reduce the risk of complications, such as infection. You'll learn how to clean the tracheostomy site, change your trach tube, suction your airways using the trach tube, and work with a home care service.

Home care services allow people who have special needs to stay in their homes. Home care services may provide medical equipment, visits from health care professionals, and help giving medicines. This service also may help with routine care of your tracheostomy.

Before you leave the hospital, you'll also learn about signs and symptoms of possible complications and when to contact your doctor or seek emergency care.

After you leave the hospital, you'll need ongoing care. Regular visits with your doctor will allow him or her to monitor your health and check for possible tracheostomy complications.