ureter

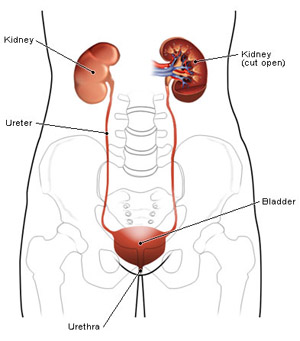

Urinary tract.

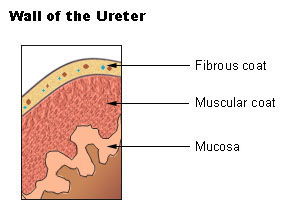

Ureter wall.

Each ureter is a small tube, 25–30 centimeters long, that carries urine from the renal pelvis (the funnel-shaped expanded upper end of the ureter) in the kidney to the urinary bladder. It descends from the renal pelvis, along the posterior abdominal wall, behind the parietal peritoneum, and enters the urinary bladder on the posterior inferior surface. The ureters join the bladder via a tunnel in the bladder wall, which is angled to prevent reflux (backflow) of urine into the ureters when the bladder muscle contracts.

The ureter is roughly the same length as the esophagus and resembles it in having three constrictions along its course: (1) where the renal pelvis joins the ureter, (2) where it is kinked as it crosses the pelvic brim, and (3) where it pierces the bladder wall.

The wall of each ureter consists of three layers. The outer layer, the fibrous coat, is a supporting layer of fibrous connective tissue. The middle layer, the muscular coat, consists of inner circular and outer longitudinal smooth muscle. The main function of this layer is peristalsis to propel the urine. The inner layer, the mucosa, is transitional epithelium that is continuous with the lining of the renal pelvis and the urinary bladder. This layer secretes mucus which coats and protects the surface of the cells.

Origin and course of the ureter

The ureter begins in the sinus of the kidney by the union of calyces. The initial section – the renal pelvis (or pelvis of the ureter – is dilated and emerges through the lower part of the hilum. It runs downward along the medial border of the kidney, tapering to become the ureter proper near the lower end of the kidney. The ureter proper descends over the back wall of the abdomen, with a slight medial inclination, and it crosses the origin of the external iliac artery to enter the true pelvis; it is often slightly constricted where it springs from the pelvis, and where it crosses the external iliac artery. In radiographs, its shadow is usually seen opposite the tips of the lumbar transverse processes, though the urethral catheter often displaces it.

Calyces

The calyces are of two kinds – lesser and greater. The lesser calyces, of which there are about ten, are the short funnel-like tubes that embrace the renal papillae and receive the urine. A lesser calyx may divide to grasp more than one papilla. The lesser calyces unite to form the greater calyces – an upper and a lower – which unite near the hilum to form the renal pelvis.

Relations of the ureter

Within the renal sinus, the renal pelvis and the calyces are surrounded by fat and the renal vessels. Outside the kidney, both renal pelvis and ureter proper lie on the psoas major muscle. Until the ureter reaches the iliac artery the only structures that intervene between it and the muscle are a thin layer of fascia, the genitofemoral nerve, and, when present, the tendon of the psoas minor.

The right ureter is a little lateral to the inferior vena cava. Its pelvic is covered by the second part of the duodenum and the renal vessels. The ureter proper is covered with peritoneum, but four sets of vessels cross in front of it, between it and the peritoneum, namely, the right colic, the testicular or ovarian, the ileocolic, and the superior mesenteric in the root of the mesentery.

The left ureter is a little lateral to the inferior mesenteric vein. Its pelvis is more exposed than that of the right; after it escapes from behind the renal vessels, it is covered only by the peritoneum. But the ureter proper, as on the right side, is separated at intervals from the peritoneum by vessels – upper left colic, testicular or ovarian, and two or more lower left colic.

Disorders of the ureter

Spasms of the ureter may occur if a kidney stone passes down or becomes lodged in the ureter. This acutely painful condition is commonly called renal colic. Ureteritis is an inflammatory condition that may occur if a ureter is blocked by a stone, or be caused by the spread of infection from the bladder.

Occasionally people are born with double (duplex) ureters, on one or both sides of the body, usually in association with partial duplex kidney on the affected side. Duplex ureters may be separate along their entire length, or they may be joined to form a Y shape. In many cases the condition causes no problems, but if duplicated ureters enter the bladder separately there may be backflow of urine into the ureter, a condition known as vesicoureteric reflux. There may also be problems such as incontinence or infection, if a ureter enters the urethra or vagina. Corrective surgery may be performed if necessary.