early Oriental and Western science

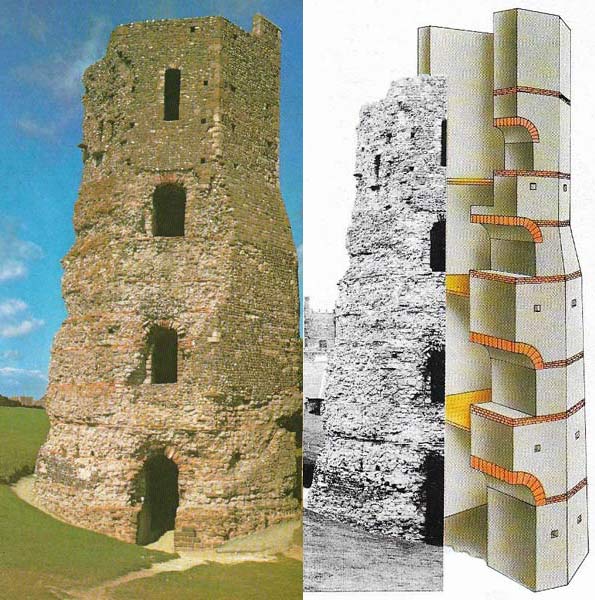

Figure 1. A Roman lighthouse, erected at Dover, was one of many such aids to shipping, a typical use of technology by the vast and efficient Roman administration. Lighting was by means of a fire, usually of wood and tarry substances, contained at the top of the building. The lighthouse was built in a stepped form like the famous Pharos at Alexandria (3rd century BC).

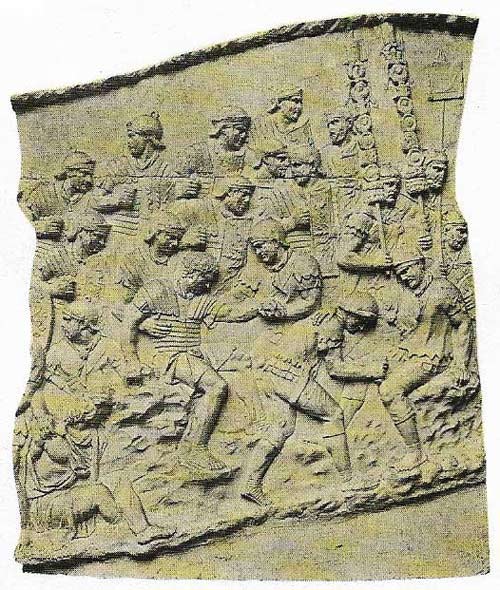

Figure 2. Trajan's Column was erected by the Roman Emperor Trajan (c. 53–117j to celebrate his victories. Built of marble and more than 30 meters (100 feet) high, it was set up in the Forum in Rome in 113. This section shows Roman legionaries being treated on the battlefield. It was here and in gladiatorial combat that Galen and other surgeons learned the basics of anatomy.

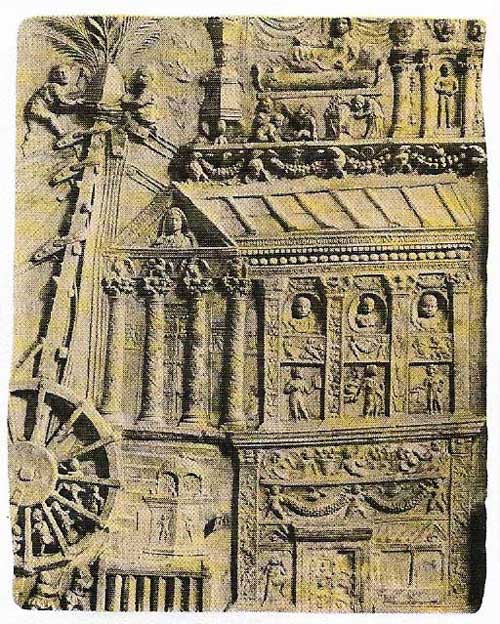

Figure 3. A crane is depicted on this section of Trajan's Column. The pulley block and ropes, and the men inside the treadmill at the bottom, can be seen clearly. Cranes such as this were found well into medieval times.

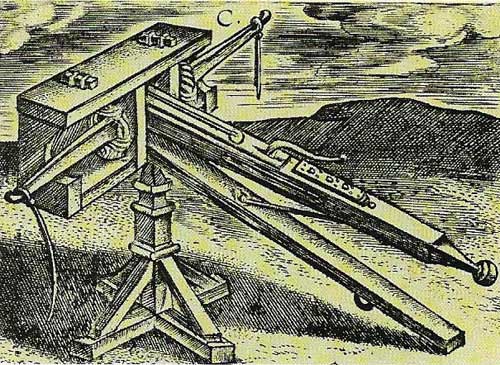

Figure 4. A euthytonon was a type of mechanical crossbow that was so large it had to be mounted on a stand and fired by a trigger mechanism. This improvement is usually credited to the mechanician Philo who worked at Byzantium (on the present-day site of Istanbul), sometime between 2000 and 250 BC. This engraving is taken from Poliorceficon, a book by Justus Lipsius (1547–1606), which was concerned with Roman armaments and was published in Antwerp in 1605.

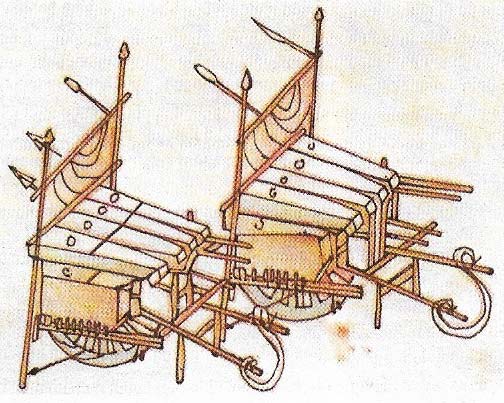

Figure 5. Gunpowder, first invented by the Chinese, was originally used for fireworks and only later adapted for war. Shown here are really wheelbarrow-like rocket launchers. Gunpowder was first mentioned by Chinese Taoist alchemists about five centuries before it appeared in Europe (c. 13th century AD). The development of the gun is more obscure because at first gunpowder was used only in rockets and bombs.

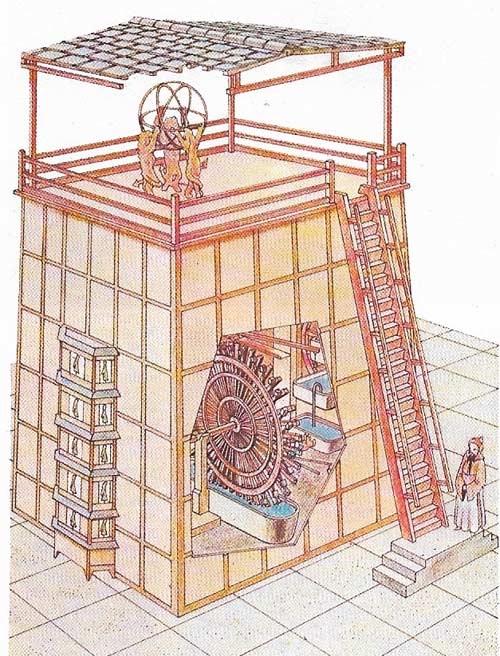

Figure 6. The first mechanical clock was Chinese, invented in the 8th century by I-Hsing. It was driven by an elaborately engineered waterwheel which acted as an escapement – the essence of all mechanical clocks. This clock was built by Su Sung about 1050. The clock was probably known in the West in the 9th century. The first European clocks with mechanical escapements were made in the 13th century.

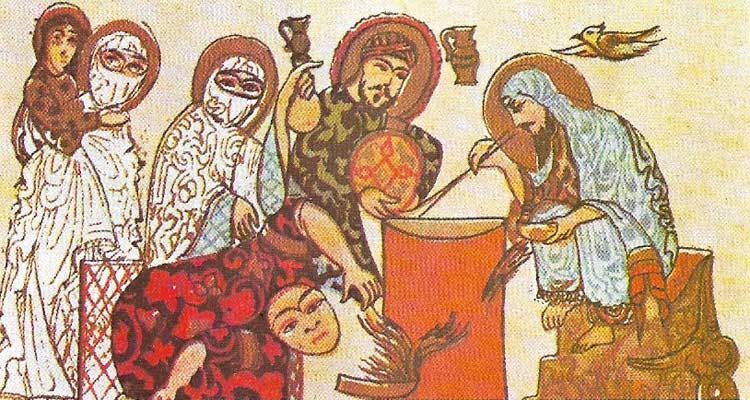

Figure 7. Scientific chemistry developed slowly. Practical chemistry, on the other hand, was part of everyday life – as epitomized here in this copy of a 12th-century Arabic manuscript showing the preparation of perfumes. Attempts were made by the Greeks and the Muslims to classify natural substances and build chemistry into a science but success did not come until the 17th century.

In Roman times there was considerable cross-fertilization between different civilizations. The Roman Empire itself, with its emphasis on foreign trade, provided regular links between the diverse civilizations of Europe, Africa, India, and even China.

The extent of Roman technology

The vastness of the Roman Empire posed immense problems in peacekeeping, in government and administration. On these counts the Romans excelled. They developed military technology, constructing large mechanized catapults, mechanical arrow ejectors, and crossbows originally invented by the Chinese in the 3rd century BC, elaborate battering-rams, and wheeled siege towers, Assyrian inventions of the 9th century BC (see Roman war machines). The large standing army required not only weapons but clothing and food and here again the Romans used the most modern techniques, establishing in the south of France, for instance, water-operated multiple flour-grinding mills.

|

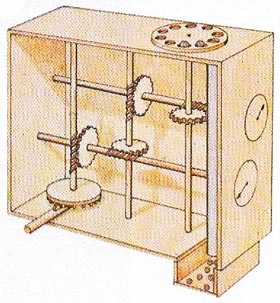

| Roman taximeters were operated by the wheels of the carriages. Worms and gear wheels reduced the rotations until dials and a counter could be run at a convenient speed. The dials had pointers that indicated the distance traveled by the carriage. The counting disk (at the top of the taximeter) allowed pebbles to drop into a holder at the bottom of the meter. By counting the number of pebbles in the holder, the fare could easily be worked out. |

Roman roads stretched throughout the empire. Most were gravelled or stone set on concrete with curb stones and drainage channels. Since the empire extended into climates much colder and damper than that of Rome, forms of central heating and damp-proofing were common, at least in the houses built for Roman officials. For their shipping, the Romans followed the example of Sostratos who, in the 3rd century BC, built a huge lighthouse at Alexandria and constructed lighthouses at many other ports (Figure 1).

Yet, expert though the Romans were in the art of running an empire and in using up-to-date technology to help them, they made no progress in pure science. Such science as they knew they obtained from the Greeks. In the 1st century AD, Pliny (23–79) had written his Naturalis Historia, a vast compendium on all known science, but this was primarily a compilation of Greek science. Galen (c. 130–c. 200) (Figure 2), the greatest medical man of Roman times, was a Greek national. As a physician and surgeon to the gladiators, Galen obtained valuable knowledge about wounds and various internal organs and later he became personal physician to the Emperor Marcus Aurelius (121–180). He took many pupils and promoted his interpretation of the operation of the human body, which was based on the idea that the liver was the main organ of the venous and arterial systems.

Advances in other centers

It was not until the 3rd century AD that there was a turn from the Greek concentration on geometry, then, in Alexandria, the mathematicians Diophantus and Pappus recommended the study of numbers and evolved a kind of algebra. Their work was extended by later generations and particularly by the Muslim civilization, where algebra became highly developed. The "Arabic" numerals, which had originally been devised in India, were adopted.

|

| Pythagoras (right), using an abacus, seems to be competing against Boethius (475–524 ) (left),who is using Arabic numerals. |

Arithmetic and a form of algebra also characterized Chinese mathematics. It was in China that the abacus was invented and it became such a useful calculator that it is still common in Japan today.

In the West, some 1,800 years and more before the Roman conquest, astronomical observations were being made in Britain with great accuracy by using stone circles, of which Stonehenge is probably the greatest example. The Chaldeans (flourished 1000–540 BC) had discovered that eclipses occurred in cycles. Yet it was not until early in the 2nd century AD that accurate eclipse predictions and studies of the earth and heavens were regularly made in China; however in the same period technological advances were accomplished. Chang Heng had invented a seismograph for recording earthquake shocks and the art of papermaking was established. By the 8th and 9th centuries AD the Chines had also invented gunpowder (Figure 5) and block printing, as well as the first clock ever to be made with an escapement – the large water clock in Sian (Figure 6). Moreover Chinese technology brought in the first efficient form of horse harness, the sternpost rudder for ships, the manufacture of silk and most importantly, the compass which was in widespread use by the 1100s.

|

| Paper was another Chinese invention that only gradually reached the West over many centuries. Known in China in the 1st century AD, the necessary technique did not reach even the Muslim world until the 8th century, and it was 400 more years before knowledge of it penetrated to Spain and the southern France. Once in the West, it still took 200 years more to reach Germany and 100 more to reach England. |

Alchemy, the forerunner of chemistry, was an ancient art of obscure origins that sought, among other things, to transform base metals such as lead into silver and gold. Carried westward, it was developed in Alexandria particularly by Zosimos in the 4th century AD, along with the important process of distillation.

Medicine and the Chinese influence

Medicine, too, was not free of mysticism and superstition, but herbal drugs were discovered and used by the Chinese, who in their pharmacopoeia had drugs against malaria and for bronchial diseases, while in India more than 500 drugs came into use, including an early form of tranquillizer. It was in China that the technique of acupuncture evolved.

After the Greeks the progress of science was slow and piecemeal, in the West at least, and seems virtually to have halted for some 600 years. Fortunately, though, the Muslims collected and collated all knowledge of Greek science and, with additions from India and the Far East, all this information filtered through to the West from the 12th century AD onwards, thus paving the way for the great scientific revival 400 years later.