polyhedron

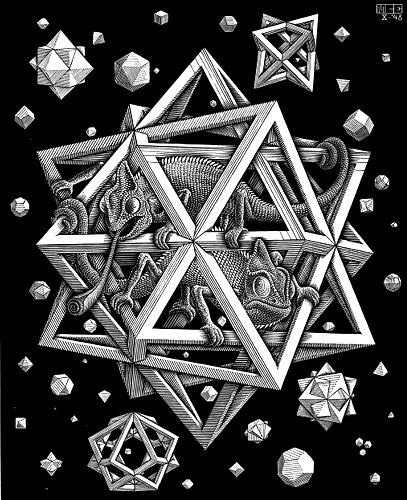

In M. C. Escher's Stars are the following polyhedra: a compound of three octahedra, a compound of two cubes with common 3-fold axis, a stella octangula, a compound of a cube and an octahedron, a rhombic dodecahedron, a cuboctahedron, a rhombicuboctahedron, a square trapezohedron, a trapezoidal icositetrahedron, a triakis octahedron, and all five Platonic solids.

A polyhedron is a three-dimensional object, or a closed portion of space, bounded on all sides by polygons (plane surfaces) and whose edges are shared by exactly two polygons. 'Polyhedron' comes from the Greek poly for 'many' and -hedron meaning 'base', 'seat', or 'face'.

Every polyhedron in three-dimensional space consists of (two-dimensional) faces, (one-dimensional) edges, and (zero-dimensional) vertices. Sometimes the term 'polyhedron' is used to apply to figures in more than three dimensions; however, analogs of polyhedra in the fourth dimension or higher are also referred to as polytopes.

The oldest known examples of human-made polyhedra were found on the islands of northeastern Scotland and date back to Neolithic times, between 2000 and 3000 BC. These stone figures are about two inches in diameter and many are carved into rounded forms of regular polyhedra. Examples including cubical, tetrahedral, octahedral, and dodecahedral forms, one which is the dual of the pentagonal prism, are on display in the Museum of Scotland and in Oxford's Ashmolean Museum.

Types of polyhedra

Compound polyhedra

A compound polyhedron is an assemblage of two or more polyhedra, usually interpenetrating and having a common center. There are two types: a combination of a solid with its dual and an interpenetrating set of several copies of the same polyhedron. The simplest example of a compound polyhedron is the compound of two tetrahedra, known as the stella octangula and first described by Johannes Kepler. This shape is unique in that it falls under both of the above classes, because the tetrahedron is the only self-dual uniform polyhedron; the edges of the two tetrahedra form the diagonals of the faces of a cube in which the stella octangula can be inscribed. Another example of a compound follows from an important Platonic relationship: a cube can be inscribed within a dodecahedron. There are five different positions for a cube within a dodecahedron; superimposing all five gives the compound known as the rhombic triacontahedron.

Convex and concave polyhedra

Polyhedra, like polygons, may be convex or non-convex. If a line that connects any two points on the surface of a polyhedron is completely inside or on the polyhedron, the figure is convex. Otherwise, it is non-convex or concave.

Irregular polyhedra

A convex polyhedron is said to be semiregular if its faces have a similar arrangement of non-intersecting regular plane convex polygons of two or more different types about each vertex. These solids, of which there are 13 different kinds, are commonly called the Archimedean solids. A dual of a polyhedron is another polyhedron in which faces and vertices occupy complementary locations. The duals of the Archimedean solids are known as the Catalan solids. A quasiregular polyhedron is the solid region interior to two dual regular polyhedra; only two exist: the cuboctahedron and the icosidodecahedron. There are also infinite families of prisms and antiprisms, which, like the Archimedean solids, are considered to be semiregular if all their faces are regular polygons. In total there are 92 convex polyhedra with regular polygonal faces (and not necessary equivalent vertices); these are the Johnson solids.

Regular polyhedra

A polyhedron is regular if all of its faces are exactly the same size and shape and if the same number of faces meet at each vertex. There are only five regular convex polyhedra – the Platonic solids. A further four regular polyhedra, the so-called Kepler-Poinsot solids, exist that are non-convex. However, the term "regular polyhedra" is sometimes used to describe only the Platonic solids.

Self-interseting polyhedra

A self-intersecting polyhedron is a polyhedron with faces that cross other faces.

Uniform polyhedra

A uniform polyhedron is a polyhedron in which each face is regular and each vertex is equivalently arranged. Uniform polyhedra include the Platonic solids, the Archimedean solids, the prisms and antiprisms, and the nonconvex uniform polyhedra.

Nonconvex uniform polyhedra

|

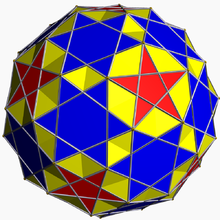

| Small snub icosicosidodecahedron |

A nonconvex uniform polyhedron is a uniform polyhedron of a type obtained by relaxing the conditions used to produce the Archimedean solids (which have regular convex faces and identical convex vertices) to allow both nonconvex faces and vertex types, as in the case of the Kepler-Poinset solids. The condition that every vertex must be identical, but the faces need not be, gives rise to 53 nonconvex uniform polyhedra. An example is the great truncated dodecahedron, obtained by truncating the corners of the great dodecahedron at a depth which gives regular decagons.

Euler's formula for polyhedra

Euler's formula for polyhedra, the oldest known formula in topology, relates the number of faces of a polyhedron, the number of edges, and the number of vertices.

Also, if A denotes the number of angles of a polyhedron, then:

A = 2E, A ≥ 3F, V ≤ 2/3 E, F ≤ 2/3 E, F ≤ 2V – 4

where E is the number of edges, F is the number of faces, and V is the number of vertices.

Reference

1. Cromwell, Peter R. Polyhedra. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.