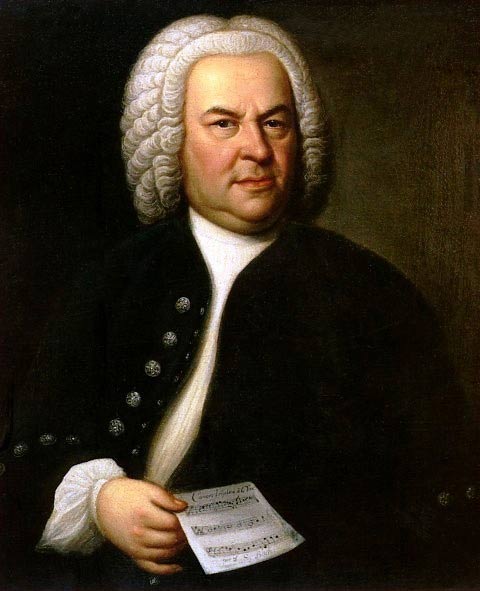

Bach, Johann Sebastian (1685–1750)

Portrait of Bach by E. G. Haussmann, 1748

The house where Bach is believed to have been born in the Rittergasse in Eisenache, Thuringia, now a Bach museum.

Thomaskirche in Leipzig, where Bach was an organist and choir-master, and where he was subsequently interred.

Bach directing a concert in 1714 at the Court Chapel in Weimar, where he worked from 1708 until 1717.

Johann Sebastian Bach was born at Eisenach, Germany, on 21 March 1685 into a family that had already produced many musicians. Among the most eminent of them were two brothers, Johann Christoph and Johann Michael Bach, cousins of Sebastian's father, Ambrosius. They wrote several motets and other compositions which later influenced Sebastian. The love of music was so general throughout the family that at Erfurt, where one branch of the clan had been settled for years, the town-musicians were commonly known as the "Bachs", even though there might not be any member of the family among them at the time.

Early years

Unlike many of his more cosmopolitan contemporaries, Bach spent his entire career in Germany – mostly in the central regions of Thuringia and Saxony. He was born into a long dynasty of Thuringian organists and composers who worked as church organists and choir-masters, municipal musicians, and at the many small princely or ducal courts which flourished in the region. Bach's father, Ambrosius, was himself employed as a musician by the town council of Eisenach, where Johann Sebastian was born on 21 March 1685.

After losing both parents by the age of ten, Bach was sent to live at Ohrdruf with his married elder brother, Johann Christoph, who was organist there. It seems likely that Johann Christoph helped with his young brother's musical training but only up to a point. Fearing that the youngster's progress might be too rapid, the elder Johann kept from him a manuscript volume of pieces by various masters. Sebastian managed to get hold of the book by drawing it through the lattice of the bookcase in which it was locked away. He then copied its contents, working only by the light of the Moon for fear of detection. His sole reward for six months' labor was confiscation of his copy on its discovery by his brother.

Once Johann Sebastian reached the age of 15, there was no longer room for him in the Ohrdruf household, and he obtained a free place at St Michael's School in Luneburg, 320 kilometers (200 miles) away in north Germany. There he benefited from a solid musical education and sang in the choir, but his formal education came to an end in 1702. After his voice broke, he continued as accompanist on the harpsichord, and also as a violinist. During this period he made several excursions to Hamburg, where a cousin of his, Johann Ernst Bach, was living, in order that he might hear the famous organist Reinken play

Weimar, Arnstadt, and Mühlhausen

At the age of 17, Bach returned to his native Thuringia to look for a job. In 1703 he was given a court appointment as a violinist at Weimar, where he had the opportunity of hearing a great deal of Italian instrumental music. He was then appointed organist at the New Church in Arnstadt, not far from Weimar, where he started to compose in earnest. Many of his church cantatas were written here, as well as the famous "Capriccio on the Departure of a Brother", composed when his brother Johann Jakob went to join the Swedish Guard. In October 1705 he obtained four weeks' leave of absence in order to go to Lubeck, 420 kilometers (260 miles) to the north, to hear Buxtehude, the great Danish organist and composer, who was then nearly seventy years old. Bach was so delighted with him and his compositions that he outstayed his leave of absence, and on his return the authorities censured his conduct in this and other matters, such as accompanying the hymns in a manner that did not suit the taste of the congregation (he had a stubborn and at times arrogant streak, which caused problems with all his employers). His intimacy with a second cousin, Maria Barbara Bach, who had lately come to Arnstadt, also earned disapproval, so that he began to look for a new post.

In June 1707 Bach left Arnstadt to take up a new position as organist at the imperial free city of Mühlhausen, some 58 kilometers (36 miles) to the northwest. His salary was now such that he felt able to marry Maria. But although his personal life had settled down, he quickly became dissatisfied with conditions at Mühlhausen, and in 1708 moved again, this time to the ducal court at Weimar.

In the early 18th century Weimar was just another small, provincial town – its period of glory was to come some 80 years later, when its residents would include Goethe, Wieland, and Schiller. Bach's job was as organist at the ducal chapel in the castle, but six of his children – including the future composers Wilhelm Friedemann (1710–1784) and Carl Philipp Emmanuel (1714–1788) – were christened at the City Church of St Peter and Paul during the Weimar years.

It was here that Bach began composing cantatas in earnest for performance at court, and he also provided instrumental music for the court orchestra. The nine years spent at the ducal court did much to perfect Bach's style as a composer for the organ, and some of the best of his cantatas were also written there. The works of the great Italian composers of the time were studied in such a manner that Bach soon became a complete master of their style of writing, and thus prepared for his own instrumental works which were to be produced later.

Bach made many journeys from Weimar, the most famous of which resulted in the embarrassment of a French harpsichord player called Marchand. In 1717 Bach went to Dresden, where Marchand's playing was universally admired. The merits of the two musicians were hotly debated, and it was determined that Bach should challenge Marchand to a public musical competition. The Frenchman accepted the challenge, but when the day came was nowhere to be found. He had realized that he was bound to lose the competition and so had beaten a retreat.

Bach's early years at Weimar were happy and productive but, after 1713, relations with his employer, Duke Wilhelm Ernst, began to deteriorate and in 1717 Bach accepted the job of Kapellmeister to the court of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen. The duke was so reluctant to let him go that he placed him under home arrest for a month. Eventually, in December 1717, the Bach family was allowed to leave.

Cöthen

While most of Bach's compositions up to 1717 had been organ works and sacred cantatas, he now exploited the instrumental resources available to him at the Cöthen court. Most of his work there was secular, since the Calvinist Prince Leopold required little sacred music. Among the works he composed during this period were the six Brandenburg Concertos for various instrumental combinations, together with concertos for violin (including the famous Double Concerto in D minor), orchestral suites, sonatas for harpsichord, violin, and flute, the suites for solo cello and the sonatas and partitas for solo violin. These works show that Bach had thoroughly absorbed the Italian style, through intensive study of works by Corelli and Vivaldi. Bach made a trip to Halle in order to seeing Handel but arrived too late to meet his great contemporary. A subsequent attempt to arrange a rendezvous also failed.

Remarriage

In May 1720, while Bach was away at a spa with his employer, Maria Barbara died suddenly. Bach remarried the next year: his bride, Anna Magdalena Wilcken (1701–1760), proved a great asset to him, both domestically and professionally –(the daughter of a musician, she was a singer, harpsichordist, and music copyist. She inherited Bach's four surviving children, to whom she added another 13, including another future composer, Johann Christian (1735–1782), later known as the "English Bach", since he spent much of his career there. Shortly after their marriage Bach began to compile two Clavierbüchlein (Little Keyboard Books) for his wife, which contain, among other works, the 15 Inventions and Sinfonias and several preludes and fugues, which were later assembled with others as Das wohltemperierte Clavier (The Well-Tempered Clavier). Much of his music exists in copies made by her hand, and many of his works for keyed instruments were written for her use.

In 1721 Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen married his cousin, and life changed irrevocably at the Cöthen court. The frivolous new princess was uninterested in music, and Bach soon felt obliged to move on – probably with some regret. In June 1722 the post or Kantor of the Thomasschule in Leipzig became vacant. The town council wanted Telemann, but he could not be released from his job at Hamburg, and so, after much deliberation, they appointed Bach. On 22 May 1723 he moved into his new quarters in the Thomasschule, where he stayed until his death 27 years later.

Leipzig

Bach's years at Leipzig, where he was required not only to teach, but also to supply music for the town's two principal churches, St Thomas and St Nicholas, were relatively uneventful, but were punctuated by acrimonious disagreements with the council over pay and conditions. Nonetheless, they were amazingly fruitful. One of his principal jobs was to write, rehearse, and direct cantatas for the Sunday services at the two churches, and his output included around 250 of these substantial works for voices, chorus, and orchestra, mostly based on well-known Protestant chorale twines.

In addition, he produced two magnificent settings of the Passion story, according to St Matthew and St John, the Mass in B minor, the Christmas Oratorio, and other major sacred works, into which he poured all the resources of vocal and instrumental writing available to him. Two movements from the Mass in B minor were presented to Augustus III at one of Bach's frequent visits to Dresden, where he received in 1736 the honorary title of Hofcomponist (court composer). A more famous visit was that paid to Frederick the Great at Potsdam, in May 1747. His arrival was announced to the king while a state concert was going on; Frederick immediately laid down his flute, and sent for Bach to come to court just as he was. Some pianos made by Silbermann were tried by Bach, who subsequently improvised on a theme given to him by the king. Subsequently, he developed this theme in many different ways and presented the result to Frederick under the title of The Musical Offering. This, like The Art of Fugue, a work begun about this time, and upon which he was engaged at the time of his death, is a monument of contrapuntal ingenuity and theoretical learning.

Towards the end of his life, several books of keyboard music were published, but Bach's fame remained local. Among his last major works were the Goldberg Variations for harpsichord, allegedly written for an aristocratic insomniac; Das Musikalisches Opfer (The Musical Offering, based on a fugue subject devised by Frederick the Great when Bach visited him at Potsdam in 1747), and the almost visionary Kunst der Fuge (The Art of Fugue), a complex series of canons on which Bach worked during the last years of his life, when his sight began to fail. He was persuaded to consult an English oculist then resident in Leipzig. The failure of an operation resulted in total blindness, and the remedies used affected his health. In July 1750 he suffered a stroke and died on the 28th of the month.

By the time of Bach's death, musical fashions were fast changing, and his music was perceived as antiquated. During his lifetime he had been more celebrated as an organist than as a composer. Unlike Mozart or Beethoven, he had little posthumous influence until Mendelssohn rediscovered his choral masterpieces in the 19th century, and his works began to be performed once more. He is now revered as one of the greatest of all composers.

No composer has surpassed Bach either in the intricacy or wealth of invention of his compositions. The broad effects which came so easily to Handel, and by which so many thousands have been impressed, did not come within Bach's province; but in his Mass in B minor, for instance, are revealed depths of sorrow and heights of ecstatic adoration, which no musician before or since has ever attained. His greatest compositions for keyed and stringed instruments, taxing as they do the utmost powers of modern artists, must have been far beyond the reach of the executants of his own day. Pianists today owe to Bach not only the system of tuning by which they can play in all keys, but the method of fingering by which all the fingers are brought into play.

One of Bach’s sons, Carl Philipp Emanuel, holds an important place in the history of music, as he did much to develop the so-called sonata-form and, moreover, became the teacher of Joseph Haydn.

Major works

Branderburg Concertos (1721); 4 orchestral suites; 7 harpsichord concertos; Goldberg Variations (1722); The Well-Tempered Clavier (1722–1744); over 200 cantatas; St John Passion (1723); St Matthew Passion (1729); Christmas Oratorio (1734); Italian Concerto (1735); The Musical Offering (1747); Mass in B Minor (1749); The Art of Fugue (1750).