protein

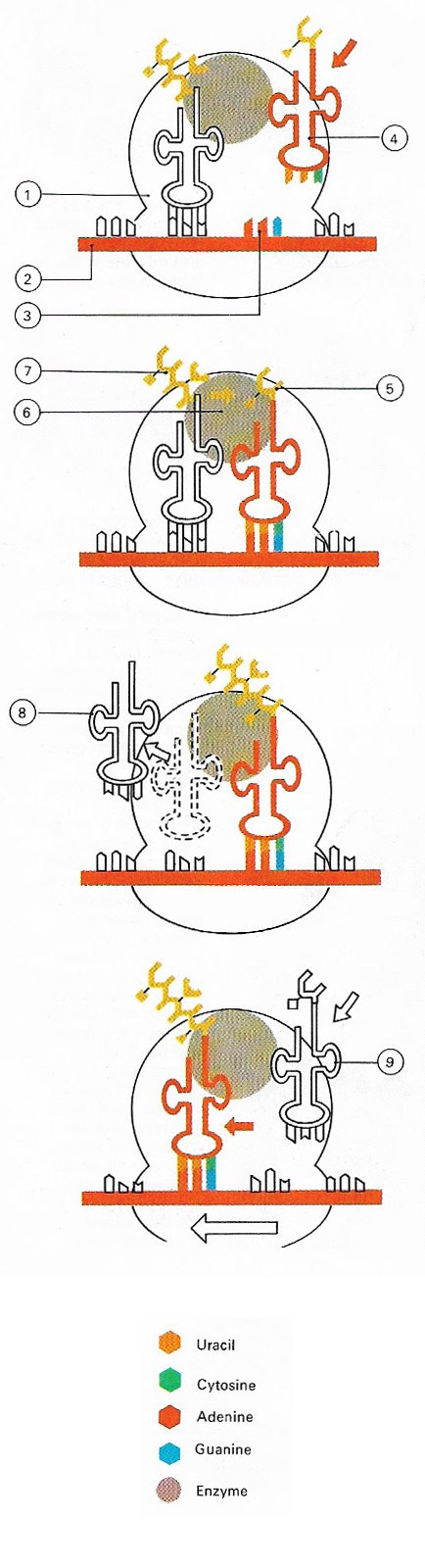

Figure 1. Proteins are assembled on particles known as ribosomes (1). The code for the protein structure is contained in messenger RNA (2). Each amino acid in the protein is coded for by a triplet of bases called a codon (3). Molecules of transfer RNA (4) bring the required amino acids (5) to the ribosomes, where the enzyme peptidyl transferase (6) links the amino acid to the growing peptide chain (7). Once its amino acid has been transferred the transfer RNA moves away (8) and a new one arrives (9). The strand of messenger RNA moves relative to the ribosome so that new codons are continuously being presented for translation.

A protein is any of a large group of macromolecules that plays a central role in the structure and functioning of living cells. Together with nucleic acids, carbohydrates, and lipids, proteins form the biochemical basis of life on Earth.

Types of protein

Classified according to molecular structure, there are three main types of protein:

Classified according to function, proteins fall into the following main groups:

Structure

Proteins are polymers made of hundreds or thousands of amino acid subunits linked by peptide bonds to give polypeptide chains. The specific amino acid sequence of a protein is referred to as its primary structure. Since, in principle, a protein can be formed from any long sequence of any or all of the 20 different amino acids found in terrestrial organisms, the potential diversity of proteins is enormous. For example, a protein containing 100 amino acids could have 20100 (about 1 followed by 130 zeros) different sequences. This almost unlimited diversity is perhaps the most important property of proteins since it enables them to perform such a wide range of functions in living organisms.

The amino acid sequence of a protein encourages the formation of hydrogen bonds between nearby amino acids. This results in two distinct types of structure. In the first, hydrogen bonds are established between different parts of the same polypeptide chain which pulls the chain into a spiral shape, known as an alpha helix. In the second, hydrogen bonds form between two adjacent chains resulting in a pleated configuration called a beta sheet. These types of folding are referred to as the protein's secondary structure. A more complex pattern of folding organizes the protein into its final, unique, three-dimensional configuration, or tertiary structure. The details of this final configuration are determined by the chemical nature of the side groups of the amino acids making up the primary structure. Many proteins associate with other polypeptide chains in clusters. Each contributing chain is referred to as a subunit and the overall structure of the cluster, the quaternary structure.

Synthesis

The synthesis of proteins involves two main stages: transcription and translation. It takes place as a ribosomes moves along a messenger RNA mold and the correct transfer RNAs, loaded with their specific amino acids, move in to recognize the triplet sequence (Figure 1). The amino acids are then released from their RNA carriers and are linked together in their specific order. The proteins so formed may be structural, as in the case of the collagen found in our skin, or more actively functional, as with enzymes.

Other hormones are themselves among the chemical signals that trigger genes to dispatch particular messenger RNAs. Similarly, other chemical signals switch off genes and stop further protein production. The structural genes that carry the code information for specific proteins do not exist in isolation. Each is associated with controlling elements in a genetic unit. Countless genetic units linked together on the long DNA molecular strand. And the DNA itself is wrapped up in association with certain proteins.

Denaturation

Since many of the bonds holding a protein in its normal shape are weak, they are easily broken by changes in the protein's environment, including the pH, the temperature, or the concentration of ions in the surrounding solution. When this happens, the protein undergoes a process called denaturation; that is, it changes shape or may even unfold and, as a result, usually becomes biologically inactive. This has particularly serious consequences if the protein is an enzyme, since such substances regulate the metabolism of living cells.