horseshoe crab

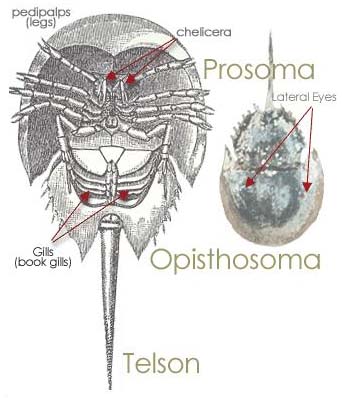

Horseshoe crab anatomy.

Eyes of a horseshoe crab.

Despite their name, horseshoe crabs are not true crabs but are much more closely related to scorpions and spiders. They have been in existence for over 300 million years and are similar in many respects to the extinct trilobites, alongside which they evolved in shallow seas of the Paleozoic era; for this reason they are often referred to as being "living fossils." Contrary to popular belief, the creature's tail, known as a telson, is not a poisonous stinger, and horseshoe crabs are completely harmless to humans.

General appearance

The four extant species of horseshoe crab range in length from 9 to 85 centimeters (3.5 to 33.5 inches), females being generally larger than males. They have an arch-shaped body, covered by a large horseshoe-shaped shell, and a long, thin tail. Along the body run numerous spines and ridges containing cuticle receptors called peg sensilla, which provide the horseshoe crab with a sense of touch. The long tail is used as a rudder while swimming, and also to flip the animal over if it becomes trapped on its back on the beach. Horseshoe crabs are generally brownish in color, ranging from greenish brown to darker, almost black shades.

Anatomy

The body of the horseshoe crab is divided into three sections: prosoma (cephalothorax), opisthosoma (abdomen), and telson (tail).

The prosoma contains the intestinal tract, the nervous system, a tubular heart, excretory glands, connective tissue, and cartilaginous plates. The opisthosoma mainly contains the musculature for the operation of the book gills and the telson.

The underside of a horseshoe crab has three main regions: the doublure, the vault, and the axial platform. The bases of the appendages attach to the axial platform, beginning with the chelicerae and ending with the book gills.

Horseshoe crabs have six paired appendages. The first pair, the chelicerae, are used to place food into their mouth. The next pair, the pedipalps, are adapted in the adult male so that the tarsus can be used as a grasping appendage; this enables the male to grasp the female during spawning. The next three pairs of legs are ambulatory and the final pair, known as pusher legs, are used for locomotion.

Toward the tail are the branchial "legs," more commonly known as book gills. Horseshoe crabs use these for both propulsion, when swimming, and respiration. The book gills consist of a membrane that allows oxygen to pass through, but keeps water out. However, water can be taken it through the book gills when necessary, for example when molting to help the animal remove its old shell. Each pair of gills has a large flap-like structure covering leaf-like membranes called lamellae. Gaseous exchange occurs on the surface of the lamellae as the gills are in motion. Each gill contains approximately 150 lamellae that appear as pages in a book.

The operculum is the first pair of the six book gills, but it serves a cover for the other five pairs which are used as respiratory organs. The operculum also houses the opening for the genital pores.

Circulatory system

The horseshoe crab has a developed circulatory system. A long tubular heart runs down the middle of the prosoma and abdomen. The rough outline of the heart is visible on the exoskeleton and at the hinge. Blood flows into the book gills where it is oxygenated in the lamellae of each gill. The flapping movement of the gills circulates blood in and out of the lamellae. Oxygenated blood is returned to the heart for distribution throughout the animal.

Eyes

Horseshoe crabs have a total of 10 eyes used for finding mates and sensing light. The most obvious eyes are the 2 lateral compound eyes. These are used for finding mates during the spawning season. Each compound eye has about 1,000 receptors or ommatidia. The cones and rods of the lateral eyes have a similar structure to those found in human eyes, except that they are around 100 times larger. The ommatidia are adapted to change the way they function by day or night. At night, the lateral eyes are chemically stimulated to greatly increase the sensitivity of each receptor to light. This allows the horseshoe crab to identify other horseshoe crabs in the darkness.

The horseshoe crab has an additional five eyes on the top side of its prosoma. Directly behind each lateral eye is a rudimentary lateral eye. Towards the front of the prosoma is a small ridge with three dark spots. Two are the median eyes and there is one endoparietal eye. Each of these eyes detects ultraviolet light from the sun and reflected light from the moon. They help the crab follow the lunar cycle. This is p> important to their spawning period that peaks on the new and full moon.

Two ventral eyes are located near the mouth but their function is unknown. Multiple photoreceptors located on the telson constitute the last eye. These are believed to help the brain synchronize to the cycle of light and darkness.

Distribution and habitat

The four species of horseshoe crabs are found in different locations around the world. The mangrove horseshoe crab is found in south east Asia, the Japanese horseshoe crab along east Asian coasts, the Atlantic horseshoe crab along the northwest Atlantic coast and in the Gulf of Mexico, and the coastal horseshoe crab in south and southeast Asia.

As juveniles, horseshoe crabs inhabit in shallow waters, but as they grow they move to deeper waters. Adults migrate from deeper waters to sandy beaches only to spawn.

Reproduction and development

The breeding season for horseshoe crabs varies depending on location, but tends to peak in May and June. The animals move to shallow waters to find a partner and mate; then they seek out beaches within bays and coves so as to be partially protected from the surf. The males arrive at the beach first and patrol along its foot waiting for the females to arrive. The females attract males using pheromones and, during peak times, there may be 5 or 6 males to one female.

During mating the male climbs onto the female's back, and the female digs out a depression in the sand. The female lays a cluster of several thousand eggs, the male fertilizes these, and then the eggs are covered over. The female returns to the beach on successive tides, laying 4–5 clutches of eggs each time. During one breeding season each female will lay up to 20 batches of eggs and a total of approximately 80,000 eggs.

The eggs take approximately 2–4 weeks to hatch. About 20 days after hatching, the young begin their first molt. The juvenile crabs spend their first two summers on the intertidal flats, feeding before the low tide and spending the rest of the day burrowed in the sand.

As they grow the young horseshoe crabs move away from the shallows into deeper water. During the first 2–3 years they molt several times. Males reach sexually maturity at 9 years of age and will have molted at least 16 times during this period; females will have molted at least 17 times during the 11 years it takes them to reach sexual maturity. At this point in their life cycle they begin the annual spawning migration back to the beaches.

Diet

Horseshoe crabs eat almost any food item that they find on the ocean floor and will also eat worms and clams, and scrape algae from rocks.

Predators

A number of shorebirds, sea turtles, invertebrates, and fish feed on the eggs and larvae of horseshoe crabs. Humans also prey upon them, using them for food and as bait to catch other ocean-dwelling animals.

Taxonomy

Limulidae is a family within the order Xiphosurida and is split into three genera that contain the four living species of horseshoe crabs. These genera are Carcinoscorpius, Limulus, and Tachypleus.

The four species of horseshoe crab are:

· Mangrove horseshoe crab (Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda)

· Atlantic horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus)

· Coastal horseshoe crab (Tachypleus gigas)

· Japanese horseshoe crab (Tachypleus tridentatus)

Medical uses

|

| A bottle of (blue!) horseshoe crab blood |

The blood of the horseshoe crab provides a valuable medical product critical to maintaining the safety of many drugs and devices used in medical care. A protein in the blood, called Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL), is used by pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers to test their products for the presence of endotoxins – bacterial substances that can cause fevers and even be fatal to humans. The LAL test is one of the most important medical products derived from a marine organism to benefit humans.

Additionally, scientific studies of the eyes of horseshoe crabs have given us a greater understanding of how the human eye works, which in turn has led to improved treatments for eye disorders.

Other interesting facts about horseshoe crabs

· A horseshoe crab's blood has a blue to blue-green color when exposed to air. The blood is blue because it contains a copper-based respiratory pigment called hemocyanin. (See also types of blood.)

· The average heart rate of a horseshoe crab is 32 beats per minute.

· Horseshoe crabs belong to the taxonomic class Merostomata which means "legs attached to the mouth."

· Horseshoe crabs have symbiotic relationships with a number of other animals, including sponges, limulus leeches, molluscs, snails, and crustaceans.