rubella

Rubella rash on a child's back.

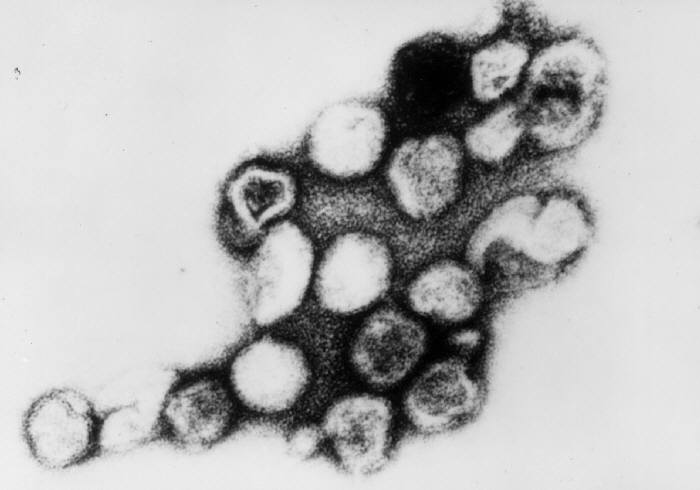

The virus that causes rubella.

Rubella, also known as German measles, is a mild viral disease, usually contracted in childhood and causing skin rash, lymph node enlargement (swollen glands), and, especially in adults, joint pain. The rash usually lasts about three days and may be accompanied by a low fever. Other symptoms such as headache, loss of appetite, and sore throat are more common in infected adults and teenagers than in children. Sometimes there are no symptoms at all.

Rubella is caused by a different virus from the one that causes regular measles (rubeola). Immunity to rubella does not protect a person from measles, or vice versa.

The importance of rubella lies in the fact that infection of a mother during the first three months of pregnancy leads to infection of the embryo via the placenta and is associated with a high incidence of congenital diseases.

Risks of rubella to the fetus

About 25% of babies whose mothers contract rubella during the first trimester of pregnancy are born with one or more birth defects which, together, are referred to as congenital rubella syndrome. These birth defects include eye defects such as cataract (resulting in vision loss or blindness), hearing loss, heart defects, mental retardation and, less frequently, cerebral palsy. Many children with congenital rubella syndrome are slow in learning to walk and to do simple tasks, though some eventually catch up and do well.

The infection frequently causes miscarriage and stillbirth. The risk of congenital rubella syndrome drops to around one percent, after maternal infection in the early weeks of the second trimester, and there is rarely any risk of birth defects when maternal rubella occurs after 20 weeks of pregnancy.

Some infected babies have health problems that aren't lasting. They may be born with low birth weight (less than 5.5 lb), or have feeding problems, diarrhea, pneumonia, meningitis (inflammation around the brain), or anemia. Red-purple spots may show up on their faces and bodies because of temporary blood abnormalities that can result in a tendency to bleed easily. The liver and spleen may be enlarged.

Some infected babies appear normal at birth and during infancy. However, all babies whose mothers had rubella during pregnancy should be monitored carefully because problems with vision, hearing, learning and behavior may first become noticeable during childhood. Children with congenital rubella syndrome also are at increased risk of diabetes, which may develop during childhood or adulthood.

Treatment of babies with congenital rubella syndrome

There is no specific treatment for congenital rubella syndrome. Certain problems that are common in the newborn period – such as blood and liver abnormalities – usually go away without treatment. Other individual birth defects – such as eye or heart defects – can sometimes be corrected or at least improved with early surgery. Babies with hearing or vision loss benefit from special education programs that provide early stimulation and build communication and learning skills. Children with mental retardation also benefit from early special education. Children with multiple handicaps may require early intervention from a team of experts.

Testing for susceptibility to rubella

There is a simple blood test that can determine whether a person is immune to rubella. The blood test shows whether or not a person has virus-fighting substances called antibodies in the blood. Rubella antibodies are produced by people who have had the illness or were vaccinated against it.

Prevention of congenital rubella syndrome

Doctors recommend that all women be tested for immunity to rubella before they become pregnant, and that they consider being vaccinated at that time if they are not immune. Vaccination will prevent rubella in susceptible women, so that their future children will be protected from the congenital rubella syndrome.

Women who missed being tested prior to pregnancy are routinely tested during an early prenatal visit. If a pregnant woman is not immune, she should avoid anyone who has this illness. There is no effective treatment for rubella during pregnancy, nor is there an effective way to prevent rubella in a susceptible woman who was exposed to the illness. Pregnant women who are not immune also should consider being vaccinated after delivery, so that they will be immune during any future pregnancies.

A woman who is breastfeeding her baby can safely be vaccinated.

The vaccine is not recommended during pregnancy, and a woman should wait at least four weeks after vaccination before she attempts to conceive.

Can vaccination against rubella around the time of conception harm the fetus?

Babies of women who were inadvertently vaccinated around the time of conception are very unlikely to be harmed by the vaccine. Between 1971 and 1989 the US government's Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) studied hundreds of women who were vaccinated from three months before to three months after they conceived. At the time they were vaccinated, the women did not know they were pregnant or would conceive in the near future. None of these women's babies had birth defects that resembled the ones that rubella causes. However, the CDC continues to recommend postponing conception for four weeks after vaccination because there is theoretically a very small risk of fetal harm.

Who else should be vaccinated?

All children should be vaccinated against rubella, unless there is a medical reason why they should not. Widespread vaccination of children helps prevent the spread of this illness to others, especially pregnant women.

The first vaccine dose is routinely given at 12 to 15 months of age, usually in combination with the measles and mumps vaccines. The combined vaccination is referred to as MMR. The child should not receive the first dose of MMR before 12 months of age. Before that, the baby still has some of its mother's antibodies, which can interfere with the vaccine and keep it from working. A second dose of MMR is given at either age 4 to 6 years or 11 to 12 years. In the US, at least 12 states now require administration of the second MMR dose before children enter kindergarten.

Vaccination of teenage or adult groups in colleges, workplaces, hospitals (staff and volunteers), or military bases helps prevent outbreaks in those areas. People working in newborn nurseries should be vaccinated, since infants born with rubella can spread it to those around them for a while after birth. Susceptible women of childbearing age also should consider being vaccinated before traveling abroad, as rubella is widespread in many countries.