cephalopod

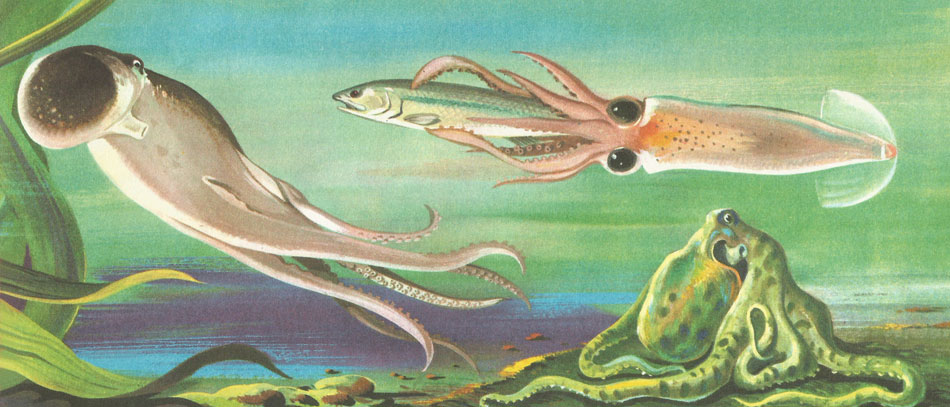

A squid devouring a herring and an octopus color matching its surroundings.

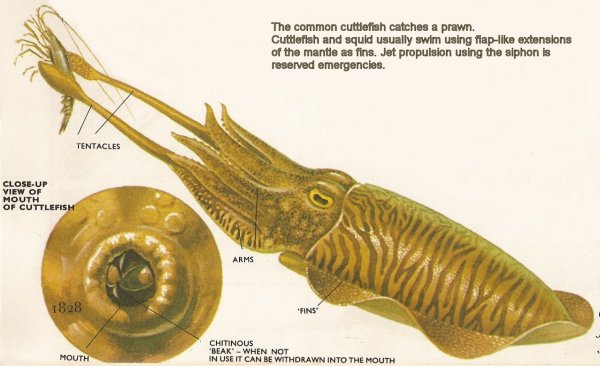

A cuttlefish catching a prawn.

Giant Pacific octopus.

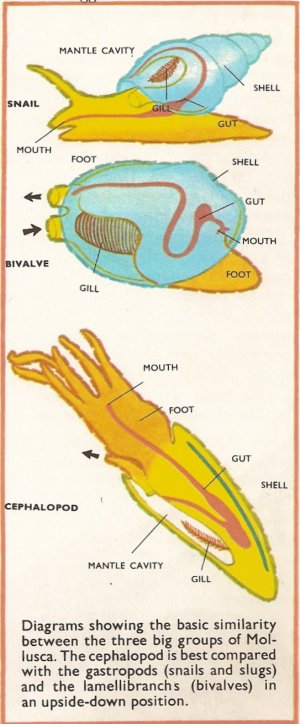

A cephalopod compared with other mollusks.

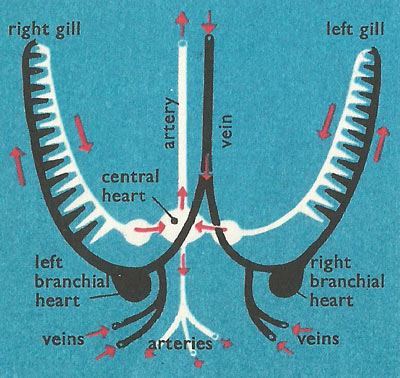

Diagram of the circulation of a dibranchiate (two-gilled) cephalopod.

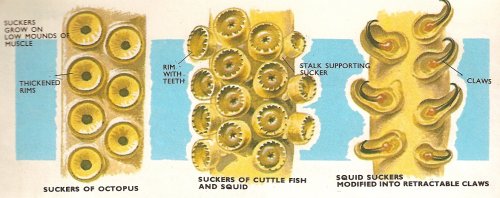

Types of cephalopod suckers.

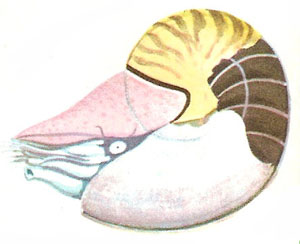

Nautilus pompilius in the swimming position. Note the compartments inside the shell.

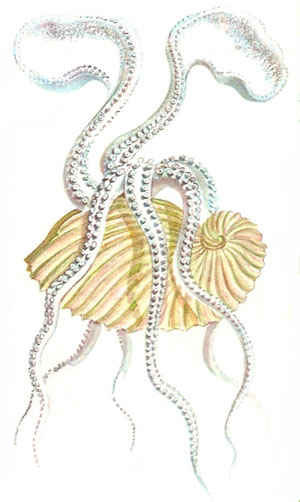

Argonauta argo.

A cephalopod is any of more than 900 species of relatively intelligent marine predators equipped with a complex and efficient nervous system. Among known cephalopods are the octopus, squid, cuttlefish, nautilus, and extinct ammonites. All cephalopods are capable of swimming by jet propulsion and have mobile tentacles for catching prey. The cephalopod eye (see octopus eye), with its well-developed retina comparable to that of vertebrates, provides a remarkable example of convergent evolution.

All cephalopods live in the sea and have soft bodies that are not divided into segments. They form a class (Cephalopoda) of the phylum Mollusca (see mollusc) – a group that also includes such creatures as the slug, oyster, and winkle. At first sight, the relationship between these animals is not very obvious. It is made clearer by considering a cephalopod in an upside-down position.

Cephalopod body structure

Like all molluscs, cephalopods have an outside layer of skin, called the mantle, which surrounds the internal organs. The shell is usually secreted inside the mantle. In octopuses it is represented by a pair of small rods or a thin plate. In cuttlefish it is better developed, and forms a calcareous, shield-shaped object familiar as the canary's cuttlebone or sea-biscuit. Squid shells are made of chitin.

Cephalopods differ from other molluscs in having a distinct head, marked off from the rest of the body by a narrower "neck". The mantle does not cover the head but stops at the neck and there forms a loose fold called the collar. The mantle is muscular and alternately expands and contracts. When expanded, surrounding sea water is drawn in around the collar. The water fills a space, which lies between the inside structures of the creature and the mantle. This is the mantle cavity and projecting into it are two delicate filaments of tissue – the gills. The gills absorb oxygen dissolved in the water.

The water does not pass out the same way as it came in. When the mantle cavity is full, the entrances at the collar are closed with valves. The mantle cavity now becomes a compression chamber. As the muscular mantle contracts, the space is reduced and water is forced out into the sea through a single narrow outlet, the siphon. The siphon is situated on the underside of the head. When necessary, water may be pumped out with great force which gives the creature jet propulsion in the opposite direction to which the siphon is pointing.

The most conspicuous structures of the cephalopods are the arms surrounding the head. The arms (together with the siphon) really correspond to the foot of the snail and mussel. The name cephalopod means in fact "head-footed" (Greek, kephale, a head; podos, a foot).

Feeding

The eight arms of the octopus are equipped with numerous suckers. There may be a single or a double row according to the species. It consists of a flat muscular disk supported on a cushion of tissue. When the octopus grabs hold of an object, the outer thickened rim of the sucker firmly presses against the surface, giving it a water-tight contact. Then the center of the disk is raised like a piston by muscular contraction. A partial vacuum is created inside the sucker and gives the octopus a strong grip. The suckers are very sensitive to mechanical and chemical sensation, and are also used as organs for exploration.

The mouth of the octopus is armed with a horny beak made of chitin. The beak consists of two hard, pointed plates which work against one another. The lower plate overlaps the upper. Poison, produced by specialized salivary glands in the mouth, quickly paralyzes the octopus's prey.

Finally, inside the mouth there is a tongue strengthened with cartilage and covered by the radula. The radula is a strip of tissue covered with rows of curved, rasping teeth. It is also found in snails.

The favorite of the octopus is crab and shellfish, though deep water forms live off dead organisms falling to the bottom. Crabs and bivalves are poisoned, then broken by the beak and cleaned out inside by the rasping radula. The bite of the beak is very powerful and can easily split quite thick bivalve shells right across.

Cuttlefish, apart from their eight arms, have two tentacles which can withdraw into pockets beside the eyes. The suckers which cover the whole of the arms and usually just the club-shaped ends of the tentacles, have teeth on the outer rims. Cuttlefish mostly live in shallow water among rocks or on sand. They live off prawns, shrimps, crabs, and small fish.

Squids also have eight arms and two tentacles. There are about 300 species and they are the commonest of all cephalopods living. The food ranges from minute floating plankton to large fish. A few squids, in addition to normal toothed suckers have some modified into retractable claws like those of a cat. Claws are excellent for obtaining a firm grip0 on slippery, fast-moving fish.

The largest species of squid, known as Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni (the Colossal Squid) grows to 14 m in length, making it the largest invertebrate.

Hunters and hunted

Octopuses are very fond of nooks and crannies on the sea floor. If they cannot find a natural den, they make one by blasting out sand and gravel with a powerful jet of water from their siphons. The entrance to their den is commonly half closed by a pile of stones and empty shells.

One method of obtaining food is to lie low in the lair and wait for unsuspecting crabs to pass by. The octopus possesses remarkable powers of changing color, surpassing even the chameleon. This ability enables it to remain well camouflaged. On the appearance of a crab a coiled-up arm is put out, and unrolled rapidly over the sea floor. On other occasions the octopus actively emerges and seeks its prey.

The ability to change color according to background is also possessed by cuttlefish and squid. The mechanism is useful not only when lying in ambush for prey. It is also valuable in avoiding enemies. Cephalopods, despite their formidable armament, have many enemies. The deadly enemy of the octopus is the voracious Moray eel, while large fish, seals, whales, penguins, and albatrosses all eat cuttlefish and squid. Even the giant squid is not without its foes. The stomachs of slaughtered sperm whales often contain undigested remains of large squids, while the surface of their skin may be scarred with the marks of the squid's 12-cm suckers.

One other device for defense is the thick, dark-colored ink secreted by an ink-sac near the gills. The ink is carried to the siphon by a long duct and from here it is discharged when the animal is in danger. It was once thought that the discharge of a cloud of ink acted rather like a smoke screen. This is probably true of cuttlefish; in other cephalopods the ink is mixed with mucus and retains a definite shape in the water, too small to conceal the animal. Most likely it acts as a dummy confusing and distracting the attacker while the cephalopod rapidly changes color and is jet propelled in a different direction. The ink also seems to paralyze the sense of smell of the attacker, giving the cephalopod an even better chance of escape.

Cephalopod intelligence

In a sense, cephalopod intelligence is a form of alien intelligence on this planet. In 1947, funds from the Marshall Plan – the US program to help rebuild Europe after the Second World War – were allocated to researchers at Naples Zoological Station to study the brain of the octopus. The results of this work, it was hoped, might help US Air Force engineers design better computers. To this day, however, cephalopod brains remain a mystery (see intelligence, nature). Although unusually large, they seem to work along fundamentally different lines from those of primates, like ourselves. Much processing in the cephalopod nervous system appears to be done in ganglia distributed around the body. Part of the reason for this is that these creatures communicate via fast-changing patterns of body color for which a distributed processing network is essential.

Evolution of the cephalopods

The fossil record of cephalopods goes back 500 million years, to late Cambrian times. These early forms, the nautiloids, all had outside shells. The shell had many chambers. The animal lived in the last one while the others were probably filled with gas for buoyancy. The nautiloids flourished for the next 200 million years and then declined. Today a single survivor remains – the pearly-shelled Nautilus. A resident of the tropical Indo-Pacific region, this is the most primitive of living cephalopods. It has a large spiral shell which is divided into a series of compartments by shell partitions. As the animal grows, it moves into successively larger compartments, leaving the vacated ones empty behind it. Nautilus differs from all other cephalopods in having four gills.

In the Devonian period, 300 million years ago, another stock branched off from the nautiloids. These were the ammonites, a group also with outside shells. Ammonites flourished particularly in Jurassic and Cretaceous times and then became extinct.

A second group which evolved from the nautiloids was the belemnites. Belemnites had no external shell but possessed an inside chambered shell partially enclosed in a supporting cylinder. Belemnites also became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period but their descendants are believed to be the octopuses, squids, and cuttlefish of today.

A link between the eight-armed octopuses and the ten-armed squids and cuttlefishes was discovered at the beginning of the twentieth century. This is Vampyroteuthis – the "Vampire squid". It lives in deep water (down to about 3 kilomeers), is about 30 centimeters in length, and has an inky blue color. There are eight normal arms which can be withdrawn into pockets. Probably the small arms functions as feelers. Like many creatures of the deep it is well equipped with light-producing organs. Possessing characters both of eight-armed and ten-armed cephalopods, Vampyroteuthis is the sole survivor of a group thought to have become extinct many millions of years ago.

Argonauta argo

Argonauta argo is really a kind of octopus which swims in the open waters of the ocean. In the breeding season two of the tentacles of the female secrete a kind of shell, very thin and delicate, and in this the eggs are laid and the young hatched. The female is quite large – the "shell" may be a foot in diameter – but the male argonaut is tiny, only half an inch long.

Remember that the "shell" of the argonaut is not at all the same thing as the true shells of other molluscs.