Project Mercury

John Glenn in orbit.

Launch of Mercury-Atlas carrying Gordon Cooper.

Mercury capsule.

Shepard photographed in flight by a 16-millimeter movie camera inside the Freedom 7 spacecraft. Shepard is just about to raise the shield in front of his face during descent after opening of the main parachute.

Schirra's Sigma 7 capsule approaching splashdown.

Project Mercury was America's first manned space program, the object of which was to put a human being in orbit, test his ability to function in space, and return him safely to Earth. Project Mercury began on 7 October 1958 – one year and three days after the launch of Sputnik 1 – and included six manned flights between 1961 and 1963. It paved the way for the Gemini and Apollo projects.

History

Drawing on work done by its predecessor, NACA (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics), NASA requested as early as 1959 proposals for a one-man capsule to be named Mercury and launched by either a Redstone or an Atlas rocket. Development of the spacecraft proceeded through a series of unmanned test flights involving different launch vehicles. Boilerplate versions were lifted by solid-fueled Little Joes, and later by Redstone and Atlas rockets, to test the capsule's structure and launch escape system. While some of these tests were successful, others blew up or veered off course. Next came flights involving real unmanned capsules, one of which (MR-1) failed moments after liftoff when the Redstone launcher simply settled back onto the launch pad. The launch escape system triggered, however, tricked into supposing an abort had happened during the ascent to orbit, and, a few minutes later the capsule parachuted back to Earth within sight of the pad. It was collected and fitted to a new Redstone which launched successfully a few weeks later. A major milestone was passed with the suborbital journey and safe return of chimpanzee Ham in January 1961. A few months later, Alan Shepard became the second primate to fly a Mercury-Redstone to the edge of space. See also Mercury Seven and Mercury Thirteen (about the women pilots who went through the Mercury tests).

| Test flights | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| test | launch date | passenger | notes |

| LJ-1 | Aug 21, 1959 | - | Abort and escape test; failed |

| BJ-1 | Sep 9, 1959 | - | Atlas-launched heat shield test |

| LJ-6 | Oct 4, 1959 | - | Capsule aerodynamics and integrity test |

| LJ-1A | Nov 4, 1959 | - | Abort and escape test |

| LJ-2 | Dec 4, 1959 | rhesus Sam | Primate escape at high altitude |

| LJ-1B | Jan 21, 1960 | rhesus Miss Sam | Abort and escape test |

| BA-1 | May 9, 1960 | - | Pad escape system test |

| MA-1 | Jul 29, 1960 | - | Qualification of spacecraft and Atlas; failed |

| LJ-5 | Nov 8, 1960 | - | Qualification of Mercury spacecraft; failed |

| MR-1 | Nov 21, 1960 | - | Qualification of spacecraft and Redstone; failed |

| MR-1A | Dec 19, 1960 | - | Qualification of systems for suborbital operation |

| MR-2 | Jan 31, 1961 | chimpanzee Ham | Primate suborbital and auto abort test |

| MA-2 | Feb 21, 1961 | - | Qualification of Mercury-Atlas interfaces |

| MR BD | Mar 24, 1961 | - | Qualification of booster for manned operation |

| MA-3 | Apr 25, 1961 | - | Test of spacecraft and Atlas in orbit; failed |

| LJ-5B | Apr 28, 1961 | - | Max Q escape and sequence |

| MA-4 | Sep 13, 1961 | - | Test of spacecraft environmental control in orbit |

| MS-1 | Nov 1, 1961 | - | Test of Mercury-Scout configuration; failed |

| MA-5 | Nov 29, 1961 | chimpanzee Enos | Primate test in orbit |

Key: LJ = Little Joe, BJ = Big Joe, BA = Beach abort, MA = Mercury-Atlas, MR = Mercury-Redstone, MS = Mercury-Scout

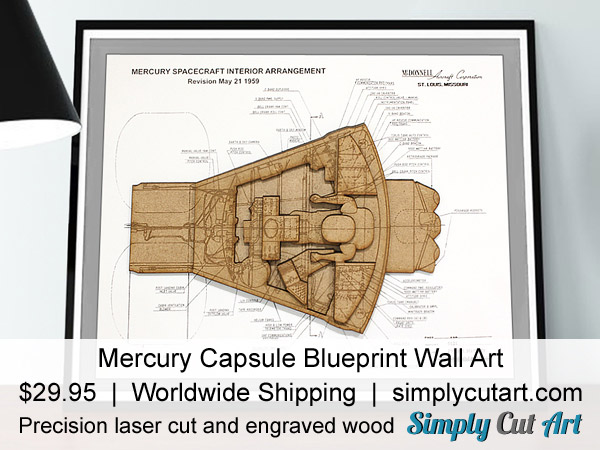

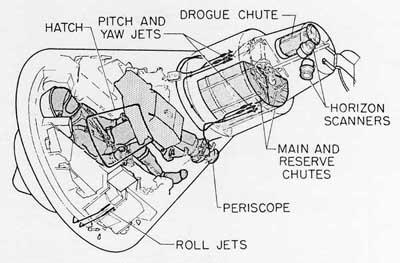

Mercury capsule

A bell-shaped capsule, 2.9 meters tall, 1.88 meters in diameter, built by McDonnell Aircraft Corp., for launch by either a Redstone or an Atlas booster. Its basic design was proposed by Maxime Faget of NACA (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics) Langley in December 1957. The pressurized cabin, with an internal volume about the same as that of a telephone booth, was made of titanium, while the capsule's outer shell consisted of a nickel alloy. Around the base, a fiberglass-reinforced laminated plastic heat-shield was designed to ablate during reentry then detach and drop about a meter to form the bottom of a pneumatic cushion to help soften the impact at splashdown. Attitude control in all three axes was achieved by 18 small thrusters linked to a controller operated by the astronaut's right hand.

|

| Glenn entering Friendship 7

|

Three, solid-fueled retrorockets, held at the center of the heat-shield by metal straps, were fired in quick succession to de-orbit then jettisoned. Above the cabin was a cylindrical section containing the main and reserve parachutes. Atop the whole capsule at launch was a latticework tower supporting a solid-rocket escape motor with three canted nozzles which could carry the spacecraft sufficiently clear of the booster in an emergency for the capsule's parachute to be deployed. Inside the cabin was a couch, tailor-made for each astronaut, facing the control panel. Early capsules had two small round portholes, but following complaints from the astronauts about poor visibility, a larger rectangular window was installed on later versions. A retractable periscope was also provided. The capsule was filled with pure oxygen at about one-third atmospheric pressure and the astronaut usually kept his helmet visor open. Only if the cabin pressure fell would he need to lower his visor and switch to his spacesuit's independent oxygen supply.

| Manned flights | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mission | launch date | vehicle | duration | orbits | pilot | capsule |

| MR-3 | May 5, 1961 | Redstone | 15 min 22 s | suborbital | Alan Shepard, Jr. | Freedom 7 |

| MR-4 | Jul 21, 1961 | Redstone | 15 min 37 s | suborbital | Virgil Grissom | Liberty Bell 7 |

| MA-6 | Feb 20, 1962 | Atlas | 4 h 55 min | 3 | John Glenn | Friendship 7 |

| MA-7 | May 24, 1962 | Atlas | 4 h 56 min | 3 | M. Scott Carpenter | Aurora 7 |

| MA-8 | Oct 3, 1962 | Atlas | 9 h 13 min | 6 | Walter Schirra, Jr. | Sigma 7 |

| MA-9 | May 15, 1963 | Atlas | 34 h 19 min | 22 | L. Gordon Cooper | Faith 7 |

Mercury MR-3

A suborbital mission which climbed high enough for MR-3 to be considered a true space flight and Shepard the first American in space. After reaching a peak altitude of 187 kilometers and peak velocity of 8,335 kilometers per hour, the Freedom 7 capsule splashed down in the Atlantic 486 kilometers downrange of the launch site. Shepard and his craft were recovered by helicopter within six minutes of splashdown and placed aboard the recovery vessel about five minutes later.

Because the planned flight was only 15 minutes long, no one gave much thought to the issue of personal waste disposal. However, Shepard was strapped into his capsule some three hours before liftoff and after a couple of hours on his back, asked for "permission to relieve his bladder." After some debate, the engineers and medical team decided that this would be OK, presumably realizing that the alternative – postponing the launch while Shepard visited the bathroom – would not amount to a NASA publicity coup. Starting with Gus Grissom's flight, strap-on urine receptacles were provided for the astronauts' use.

During the flight, Shepard experienced a maximum 6g during ascent, about five minutes of weightlessness, and slightly under 12g during reentry. He successfully completed all his assigned tasks, including manually guiding the capsule in a specific direction from the time it separated from the Redstone booster. This demonstrated to NASA that a human could handle a vehicle during weightlessness and high gravity stresses without adverse physiological effects. The Freedom 7 capsule did not have a window, but Shepard was able to see outside through a periscope – but only in black-and-white because a gray filter had been mistakenly left on the lens.

Mercury MR-4

|

| Grissom climbing into Liberty Bell 7. |

Launch attempts on 18 and 19 July 1961, were scrubbed due to bad weather – the first scrubs in the history of American manned spaceflight. On his suborbital flight, Grissom became the second American in space, reached a maximum altitude of 190 kilometers and ended up 488 kilometers downrange of the launch site. The mission objectives were almost identical to those of the Shepard's flight but the Liberty Bell capsule had a window, easier to use hand controls, and explosive side hatch bolts that could be blown in an emergency.

Unfortunately, after splashdown these bolts were unexpectedly blown, causing the capsule to start filling with water. Grissom made his way out but had to struggle to reach a sling lowered from a rescue helicopter because his spacesuit had become waterlogged. He was rescued without injury after being in the ocean for about four minutes, but an attempt to lift the water-laden Liberty Bell capsule by helicopter failed and the capsule sank. This was the only capsule not recovered following an American manned spaceflight. NASA ran a battery of tests and simulations to find out how Grissom might have blown the hatch and determined that it would have been nearly impossible for Grissom to have done this accidentally. Instead the loss of the capsule was blamed on an unknown failure of the hatch itself, although it became a standing joked that a crack which had been painted on the side of Liberty Bell 7 prior to the flight was the real cause of its sinking.

Following the successes of missions MR-3 and MR-4, NASA decided that no more suborbital flights were needed before a manned orbital attempt and so cancelled the flights that had been designated MR-5 and MR-6.

Mercury MA-6

|

| The 20 February 20 1962 launch of the Mercury capsule Friendship

7. Aboard it, John Glenn became the first American in orbit

|

After a series of scrubs that delayed his launch for nearly a month, John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth. His Friendship 7 capsule completed a 130,000 kilometers flight, three times around the planet, with Glenn becoming the first American astronaut to view sunrise and sunset from space and to take pictures in orbit – using a 35 millimeter camera he bought in a drugstore.

|

| Glenn on his first orbit in Friendship

7

|

Glenn also had the distinction of being the first American astronaut to eat in space, consuming a small tube of apple sauce, and of discovering what became known as the "Glenn Effect." Early in the flight, he noticed what looked like fireflies dancing outside his window. These were later identified as frost particles sparkling in the sunlight after being released from the spacecraft's attitude control jets.

During the second and third orbits, Glenn took manual control of Friendship 7 due to a failure of the automatic pilot caused by one of the control jets becoming clogged. Far more worrisome was a potential problem that mission managers became aware of as Glenn prepared to leave orbit. At first, they hid their concern from the astronaut. But when Glenn was asked to carry out unfamiliar instructions, he asked the reason and was told there was a possibility that the capsule's landing bag and heat-shield had come loose. The landing bag was designed to absorb the shock of water impact, and the heat-shield was essential to prevent the spacecraft from burning up during reentry. Glenn was instructed to delay jettisoning the capsule's retrorocket package in hope that the straps which held it to the capsule might keep the potentially loose heat-shield in place until the last possible moment. Glenn later recalled that he saw the burning retrorocket package pass by outside his window, causing him to believe his spacecraft on fire. Anxious moments passed for those on the ground during the time of communications blackout, but Glenn's capsule returned safely and the problem was later traced to a faulty switch in the heat-shield circuitry which gave a false reading.

Friendship 7 splashed down in the Atlantic 267 kilometers east of Grand Turk Island and remained in the water just 21 minutes before being picked up by helicopter, Glenn staying inside his spacecraft until it was on the deck of the recovery vessel.

Mercury MA-7

|

| Launch of Mercury-Atlas carrying

Carpenter and Aurora 7

|

Scott Carpenter became the second American to orbit Earth, flying a similar mission to Glenn's but with some extra activities. Aurora 7 carried two experiments – one to test the way liquids react in weightlessness and the other, a balloon, intended to provide drag and visual data; however, the balloon failed to inflate outside the capsule as planned. Carpenter performed more on-orbit maneuvering than Glenn, although this was curtailed when mission managers grew concerned that too much fuel was being used. He also became the first American astronaut to eat an entire meal in space, squeezed Glenn's apple sauce, out of tubes.

A three-second delay in beginning the reentry burn together with a 25° yaw error at the time of firing meant the capsule overshot the intended recovery area by 400 kilometers, splashing down about 200 kilometers northeast of Puerto Rico. Carpenter climbed out his capsule and then had to wait about three hours until the recovery crew arrived.

Mercury MA-8

Although NASA was concerned a couple of days before launch that Tropical

Storm Daisy on 1 October 1962, might pose a threat, Wally Schirra took off aboard Sigma 7 on schedule. The capsule for this mission had been

modified to avoid problems that had cropped up on previous flights. Its

reaction control system was modified to disarm the high-thrust jets during

periods of manual maneuvering, and the mission had more scheduled "drift

time" (periods of unmaneuvered flight), to save fuel. As it happened,

the spaceflight deviated so little from its planned trajectory during its

drift times that fuel economy on future flights was much improved.

Two high-frequency antennas were mounted onto the retro package to provide

better communications between the capsule and the ground during the flight.

Schirra operated an experimental hand-held camera and took part in the first

live television broadcast to be beamed back to Earth during an American

manned spaceflight. The signal was transmitted to North America and Western

Europe via Telstar-1. Nine ablative-type

material samples were included in an experiment package mounted onto the

cylindrical neck of the capsule. Also, two radiation monitoring devices

were carried inside the capsule, one on either side of the astronaut's couch.

Shortly after Schirra's return, the Air Force announced that he would likely

have been killed by radiation if his spacecraft had flown above an altitude

of 640 kilometers. Radiation monitoring devices on classified military satellites

had confirmed this lethal radiation, which resulted from a high-altitude

nuclear test carried out in July 1962. In fact, at the height at which Schirra

actually flew, the radiation monitoring devices inside the spacecraft confirmed

that he had been exposed to much less radiation than predicted even under

normal circumstances. The mission showed that longer duration spaceflights

were feasible, and Schirra commented that both he and the spacecraft could

have flown much longer than six orbits. Splashdown took place within the

intended recovery zone, about 440 kilometers northeast of Midway Island and just

9 kilometers from the recovery vessel.

Mercury MA-9

|

| Cooper in Faith 7 after hatch was

blown

|

Lying in his Faith 7 capsule during countdown, Cooper was so relaxed that he even managed to nod off. He had another opportunity to sleep once in space because this 22-orbit mission was the first in American manned spaceflight history to last more than a day. (Vostok 2, however, holds the record for the first full-day manned mission of all.)

During the flight, Cooper released a beacon sphere containing strobe lights – the first time satellite to be deployed from a manned spacecraft – which he was able to see during his next orbit. He also spotted a 44,000-watt xenon lamp that had been set up as an experiment in visual observation in a town in South Africa, and was able to recognize cities, oil refineries, and even smoke from houses in Asia. Cooper attempted twice unsuccessfully to deploy an inflatable balloon. Between orbits 10 and 14 he slept for about eight hours, later reporting that he had anchored his thumbs to his helmet restraint strap to prevent his arms from floating freely – a potential hazard with so many switches within easy reach.

On the 19th orbit a warning light came on indicating that the capsule had dipped to an unacceptably low altitude. However, further tests showed that the capsule was still in its proper orbit, leading to a conclusion that the warning system had failed, possibly due to a short-circuit caused by dampness in the electrical system. Fearing there might be more such short-circuits in the automatic reentry system, mission managers instructed Cooper to reenter under manual control – the only such reentry of all four Mercury orbital flights. In the event, Cooper did a fine job bringing his capsule to a splashdown just 7 kilometers from the prime recovery vessel.

Cooper was the last American astronaut to orbit Earth alone. NASA had considered one more Mercury flight, but the Project officially ended on 12 June 1963, when NASA Administrator James Webb told the Senate Space Committee that no further Mercury missions were needed, and that NASA would press ahead with the Gemini and Apollo programs.