skeletal muscles and muscle groups

Figure 1. Muscles at the front of the human body.

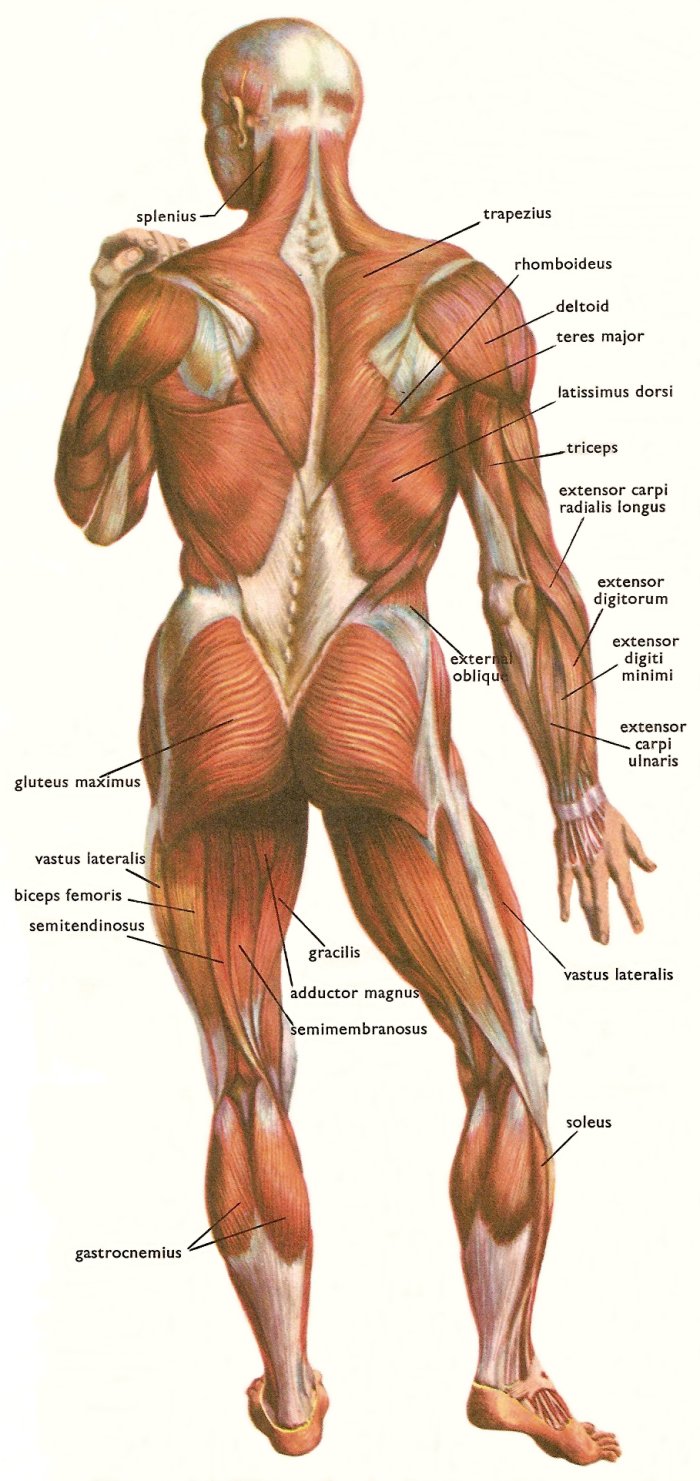

Figure 2. Muscles at the back of the human body.

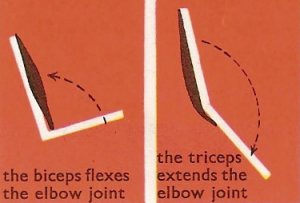

Figure 3. Actions of the biceps and triceps muscles.

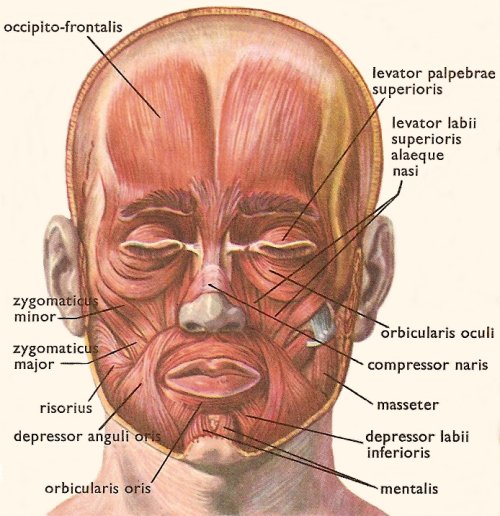

Figure 4. Muscles of the head.

Introduction

There are more than 600 skeletal muscles in the human body, which together account for about 40% of a person's weight. Skeletal muscles are also called voluntary muscles because, unlike the other two types of muscle in the body, smooth muscle and cardiac muscle, they are under conscious control.

The most important and unique feature about muscle tissue is that it is able to contract (shorten) when stimulated by nerve impulses. (See muscle operation and contraction by nerves.) In a strong contraction the length of a muscle is reduced to about 60% of its length when relaxed. At the same time, the muscle becomes much thicker.

Names of the skeletal muscles

Most skeletal muscles have Latin names that describe some feature of the muscle; the more familiar ones also have everyday names, such as the hamstring muscles at the back of the thigh, and the calf muscles which straighten the ankle. Often several criteria are combined into one name. The following are some terms relating to muscle features that are used in naming muscles.

Some specific skeletal muscles

How muscles work

The muscles that move the trunk and the limbs are arranged so that each muscle passes over one or more joints and is attached to the bones on each side. When a muscle receives a nerve impulse it immediately contracts, and its two ends are drawn closer together. Since the ends of the muscle are attached to bones on either side of a joint, these bones are drawn together with the muscle, and in this way the position of the joint is altered.

Most joints are moved by groups of muscles rather than by a single muscle working alone. Furthermore, each joint has muscles that move it in each direction. The elbow joint, for example, is flexed, or bent, by the biceps brachii muscle and extended, or straightened, by the triceps muscle (see illustration [3]). These two muscles have to act together, because when one is contracting, the other must relax. It it did not, the joint would not move but would merely be firmly fixed.

In our legs the muscles are often used to fix the joints. If you stand on one leg you can feel the muscles of the knee contracting to keep it straight.

The ways muscles work

A muscle may work in the following ways: as (1) a prime mover, (2) an antagonist, (3) a fixator, and (4) a synergist.

Prime mover

A muscle is a prime mover when it is the chief muscle or member of a chief group of muscles responsible for a particular movement. For example, the quadriceps femoris is a prime mover in extending the knee joint.

Antagonist

Any muscle that opposes the movement of the prime mover is an antagonist. For example, the biceps femoris opposes the action of the quadriceps femoris when the knee joint is extended. Before a prime mover can contract, there must be equal relaxation of the antagonist muscle; this is brought about by nervous reflex inhibition. (See Figure 3.)

Fixator

This is a muscle that contracts isometrically to stabilize the origin of the prime mover so that it may act efficiently. For examples, the muscles attaching the shoulder girdle to the trunk contract as fixators to allow the deltoid to act on the shoulder joint.

Synergist

There are many examples in the body where the prime-mover muscle crosses a number of joints before it reaches the joint at which its main action takes place. To prevent unwanted movements in an intermediate joint, groups of muscles called synergists contract and stabilize the intermediate joints. For example, the flexor and extensor muscles of the carpus contract to fix the wrist joint, and this allows the long flexor and extensor muscles of the fingers to work efficiently.

Attachments of muscles

Most skeletal muscles are attached at each end to one or more of the bones of the skeleton. The attachment nearer to the center of the body, or which moves least when the muscle contracts, is usually called the origin. The attachment that is farther away from the center of the body, or which moves more, is called the insertion.

Not all our muscles are to be found close to the parts of the body which they move. Some of the muscles that bend and straighten the fingers, for example, are not in the hand but in the forearm. The ends of these muscles are joined to their insertions in the fingers by long tendons. It is along these tendons that the muscles exert their power. If you straighten your fingers you can clearly see four of these tendons running down the back of your hand.

Nerve supply of the skeletal muscles

The nerve impulses from the brain which make the skeletal muscles work pass down the spinal cord and then out along the appropriate spinal nerves to the muscles. Some of the muscles of the head and face, however, are supplied by cranial nerves which run direct from the brain.

The nerve supply to a muscle is a mixed nerve, about 60% being motor and 40% sensory, and it also contains some sympathetic autonomic fibers. The nerve enters the muscle at about the midpoint on its deep surface, often near the margin; the place of entrance is known as the motor point. The arrangement allows the muscle to move with the minimum interference with the nerve trunk.

The motor fibers are of two types: the larger alpha fibers derived from large cells in the anterior gray horn, and the smaller gamma fibers derived from smaller cells in the spinal cord. Each fiber is myelinated and ends by dividing into many branches, each of which ends on a muscle fiber at the motor end plate. Each muscle fiber has at least one motor end plate; the longer fibers possess more.

The sensory fibers are myelinated and arise from specialized sensory endings lying within the muscle or tendons called muscle spindles or tendon spindles, respectively. These endings are stimulated by tension in the muscle, which may occur during contraction or by passive stretching. The function of these sensory fibers is to convey to the central nervous system information regarding the degree of tension of the muscles. This is essential for the maintenance of muscle tone and body posture and for carrying out coordinated voluntary movements.

The sympathetic fibers are nonmyelinated and pass to the smooth muscle in the walls of the blood vessels supplying the muscle. Their function is to regulate the blood flow to the muscles.

Muscles of the trunk

Refer to Figures 1 and 2 for the muscles described in this and the next two sections.

The muscles of the trunk include those that move the spinal column, the muscles that form the thoracic and abdominal walls, and those that cover the pelvic outlet.

The erector spinae group of muscles on each side of the spinal column is a large muscle mass that extends from the sacrum to the skull. These muscles are primarily responsible for extending the spinal column to maintain erect posture. The deep back muscles occupy the space between the spinous and transverse processes of adjacent vertebrae.

The muscles of the thoracic wall are involved primarily in the process of breathing. The intercostal muscles are located in spaces between the ribs. They contract during forced expiration. External intercostal muscles contract to elevate the ribs during the inspiration phase of breathing. The diaphragm is a dome-shaped muscle that forms a partition between the thorax and the abdomen. It has three openings in it for structures that have to pass from the thorax to the abdomen.

The abdomen, unlike the thorax and pelvis, has no bony reinforcements or protection. The wall consists entirely of four muscle pairs, arranged in layers, and the fascia that envelops them. The abdominal wall muscles are identified in the illustration above.

The pelvic outlet is formed by two muscular sheets and their associated fascia.

Muscles of the upper extremity

The muscles of the upper extremity include those that attach the scapula to the thorax and generally move the scapula, those that attach the humerus to the scapula and generally move the arm, and those that are located in the arm or forearm that move the forearm, wrist, and hand.

Muscles of the lower extremity

The muscles that move the thigh have their origins on some part of the pelvic girdle and their insertions on the femur. The largest muscle mass belongs to the posterior group, the gluteal muscles, which, as a group, abduct the thigh. The iliopsoas, an anterior muscle, flexes the thigh. The muscles in the medial compartment adduct the thigh.

Muscles that move the leg are located in the thigh region. The quadriceps femoris muscle group straightens the leg at the knee. The hamstrings are antagonists to the quadriceps femoris muscle group, which are used to flex the leg at the knee. The muscles located in the leg which move the ankle and foot are divided into anterior, posterior, and lateral compartments. The tibialis anterior, which dorsiflexes the foot, is antagonistic to the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, which plantar flex the foot.

Muscles of the head and neck

A few of our skeletal muscles are unusual in that they are not attached to bone, but are simply placed within soft tissues. Several muscles of this type are found in the face (Figure 4).

Humans have well-developed muscles in the face that permit a large variety of facial expressions. Because the muscles are used to show surprise, disgust, anger, fear, and other emotions, they are an important means of nonverbal communication. Muscles of facial expression include frontalis, orbicularis oris, laris oculi, buccinator, and zygomaticus.

There are four pairs of muscles that are responsible for chewing movements or mastication. All of these muscles connect to the mandible and they are some of the strongest muscles in the body.

Numerous muscles are associated with the throat, the hyoid bone and the vertebral column. Two of the more obvious and superficial neck muscles are the trapezius and sternomastoid (sternocleidomastoid).